| |

The conversation that appears below between Ron Janowich, painter, and Robin Hill, sculptor, was conducted specifically for the Cultural Recycling issue of Other Voices. Here Hill answers questions about her work, which reincorporates the detritus of the everyday world into labor-intensive, abstract compositions. Her work pushes beyond the rubric of recycling into an area that has more to do with transcendence and perception, and which resonates with ideas about the economy of her creative process.

RJ: Robin, it's been some years since your last show at Lennon, Weinberg Gallery, and coming up is the first one-person exhibition you've had in New York, since you moved to California three years ago. I would imagine that, since your work is highly sensitive to the environment that you live in, the move must have had a rather profound effect on your work. Could you talk a little bit about how you feel about the move now that you're a few years into it?

RH: I lived in New York City for 25 years before moving to California. The biggest challenge I faced upon arriving on the west coast was having no familiar landmarks. I went into architecture withdrawal first, followed by population withdrawal, traffic withdrawal, and fashion withdrawal; nothing looked the same. I realized how much of an influence these qualities had on my sense of purpose as an artist. Suddenly, things felt inauthentic and artificial. As a way of reconnecting, I recreated my Brooklyn studio in California.

Some people would use a move of this magnitude as a opportunity to give old work the heave ho and start fresh but, for me, keeping things the same was what I needed. I laid out all the same works-in-progress from my Brooklyn studio in hopes that I could pick up where I left off. In New York City, artists can't help but feel part of a critical mass of creativity; no matter how isolated they may feel. In California I had to confront an eerie silence, a ringing in my ears, which people experience when they move suddenly from noisy places into silent ones. I am now living in the very quiet, agricultural, valley town of Woodland near the university town where I teach in Davis, California. I can't talk about my move without mentioning September 11. The attacks on the World Trade Towers happened in our wake, in our rear view mirror, sixteen days after our arrival in California. I ended up having to start over in a much more profound way, even though I had so carefully figured out how not to. Everyone I know felt like they were starting over.

RJ: I think the scale of that disaster had that effect on a lot of people.

RH: The way we looked at art after that day changed. Frivolous things were referred to as "from before". In looking at my immediate world through the lens of that event, I found myself thinking a lot about landmarks and about the forms of the World Trade Towers. Two grain silos by the roadside became tower surrogates. And I remember looking at Catherine Murphy's drawing "Swept Up," of her studio floor sweepings, and practically weeping in front of it because it was suddenly the rubble at Ground Zero. Things started to take on this sort of archetypal quality that resonated with metaphors of that event.

RJ: I think it's quite different to make a move after spending twenty years in one specific place than it would be if you were starting out your career as an artist. For instance, there would be a natural tendency to carry your history with you. I think this would be true of physical objects that you value, which hold important traces of the place that you are leaving. As with any move, there is an editing process that happens. We tend to take with us what we feel will be important to our new lives. What did you decide to take and what did you decided to leave?

RH: I decided that there was no way I could anticipate what my new life would be like. Because I had the luxury of being relocated by the university, I decided to take everything. It bordered on the ridiculous, but it was important to me that I take all the debris and the detritus from my studio. These were the things that I had accumulated and collected, that were positioned for unknown purposes in my work. The move was almost a conceptual project. It was epic.

RJ: I liked what you said once about taking a 2x4 piece of lumber, and other assorted materials, as if they were sacred objects or touchstones for transition.

RH: Those things are sitting in my Woodland studio now; blocks of hardwood, wooden rings and balls, barrels of balsa wood. My supply of urban off-sheddings feels finite now, until I get closer to the new forms of off-sheddings here. I have started looking at the landscape in California as a resource recently. The tumbleweed might be the equivalent of the airborne bag that I have made a lot of work with. I feel that it's just a matter shaping sensitivity to what's here as opposed to what's not here. I covet the materials that I gathered from the streets and factories of New York, as if they were on the verge of extinction. Oddly, I think the materials I have been working have come to me on the tide of a much greater obsolescence…the shift from 19th century industrial processes to the digital, the virtual, and the outsourced. An on-going concern in my work has been the idea of economy, of resourcefulness. I try to resist the conventional notion of progress that demands that things always be new and improved. This form of resourcefulness I'm talking about involves a willingness to shift one's perception to embrace small as big, simple as complex, low-end as high-end, accidental as purposeful, incidental as noteworthy. It will be a challenge to see how I continue this way of working and thinking in my new environment.

RJ: The ability to find seems like an important baseline for your work, maybe even more important than the ability to make, as would be the case in traditional sculpture. In some ways I'm thinking of the difference between a photographer and a painter. A photographer finds and mechanically records the find, while the painter makes his vision through the mediation of touch, through his hands. Could you go a little further into what exactly the process of finding is for you, and how you transform whatever the found is, into your vision?

RH: I've learned that what I used to see as a handicap is actually a sensibility. It's one that many others share. And I think I've had this sensibility since I was very, very, young. In art school I was mining the magic of mechanical reproduction processes, like the bellows copy camera, and diazo blueprint machines.

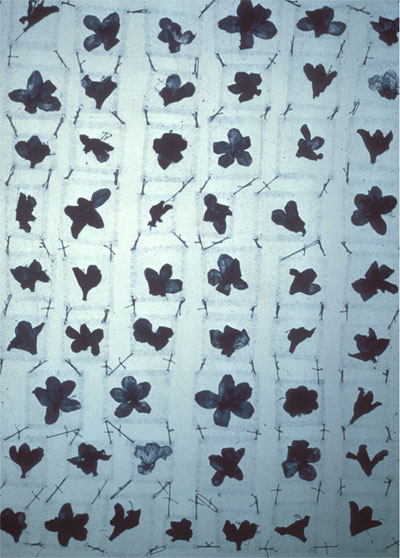

My approach was to see what the processes could do independently of any particular idea I might have, using mostly found materials. My grandmother's lace wedding dress, Chinese calligraphy books, and pressed azaleas were some of the materials I worked with. The ideas came from the processes. This was one of the ideas of minimalism, or post minimalism, the idea of meaning residing in process. This is the art that I cut my teeth on as a young artist, exhausting materials for all their potential. It is important to me to stay open to the outcome, to encompass accidents and chance. The way that finding factors in to my work is in the collection of random materials, situations, phenomena, and in making a decision to wrestle the collections into artwork of my own. There is something contradictory about that because many of the things I find are already perfect in their own given form. So, more than anything, I'm simply adding onto something, building onto it, amplifying it in the world. I'm giving it a voice. We all gaze on simple, urban phenomena, like airborne trash. I'm not claiming anything, because the things that I'm working with are totally in the public domain. Sometimes I think of my art as an acknowledgement, like the thousands-year-old art tradition from China and Japan known as scholars' rocks or spirit rocks. The rocks are collected for their contemplative potential and are meticulously presented on handcrafted pedestals that are designed for one particular rock. It's the pedestal that transforms that object from just something in nature to an art work. I once gathered the remainders of a project and assembled them into a scholars' rock of my own, in a piece called paper stack with plaster rock. These objects are tiny but through that act of claiming them and acknowledging them, they become monumental. I would like to think that I'm capturing things, whether they're poetic or mundane, with respect for whatever their given qualities are.

RJ: I think that's a really important point. I think it's the essence of what you're about as an artist. It's more than just the find; it's more than just the inherent perfection of whatever object you discover. It's your transformation of that object in context and meaning.

RH: There's a Sufi saying that I really love; whatever you are looking for is looking for you too. The idea is that there are things in the world that you encounter because of your preparedness for finding them. Louis Hyde talks about it in a wonderful essay on chance and creativity. He says: what a lucky find reveals first is neither cosmos nor chaos, but the mind of the finder. It might even be better to drop cosmos and chaos, and simply say that the chance event is a little bit of the world as it is, a world always larger and more complicated than our cosmology. And that smart luck is a kind of response to intelligence, invoked by whatever happens. This idea took root in a piece called Bushwick Wheel. I gathered orange peels on a daily basis form a person who sold bags of peeled oranges from a median in the road to drivers sitting at a red light in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn. We developed a kind of symbiosis. He was relieved of having to haul his trash and I acquired an abundant source of a beautiful strange new material. That piece actually led me into very new territory, not the least of which was the territory of chance.

RJ: I think Hyde's quote is beautifully accurate. Your finding that quote is a perfect example of the kind of preparedness that informs what we notice.

RH: On some level my ideas are about the idea of not having ideas. I remember thinking about this as a student at the Kansas City Art Institute. A professor, Dale Eldred, who died a tragic death in his studio in the horrible floods of 1993, came up to congratulate me on my thesis exhibition. And I said something like, thanks, but anybody can do this. Looking back, I laugh at my naivety. Was that the point? To make sure that someone looking at my work would feel included to the point of being able to do it too? I realize that those were the seeds of what I am doing now. At that time it was more it about my personality than it was about my work. But as I've grown older, I've figured out how to use that attitude in my work. In my last show at Lennon-Weinberg Gallery I used the language of cookbook recipes in the titles of the pieces, as in add air, let sit and place tape on paper, expose to light, wait. My purpose, and some people really got it, was to create a subtext of approachability, of commonness, that I want to champion. It's not really a cause, but it is a visual form of modesty that I feel is valuable.

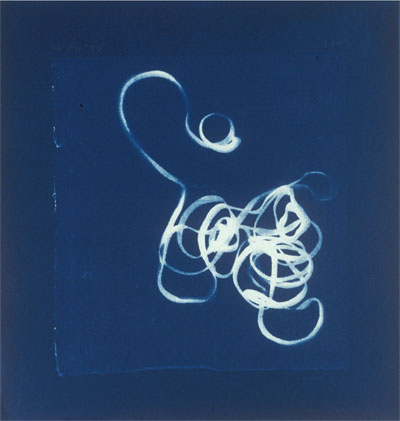

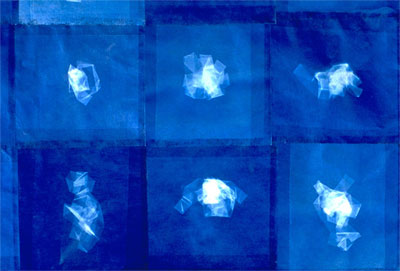

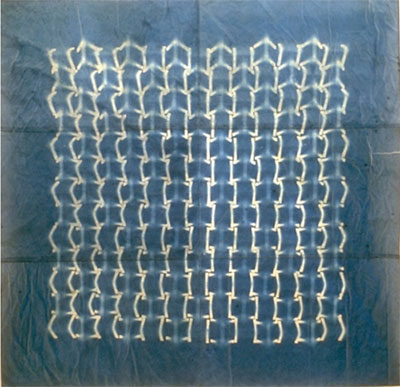

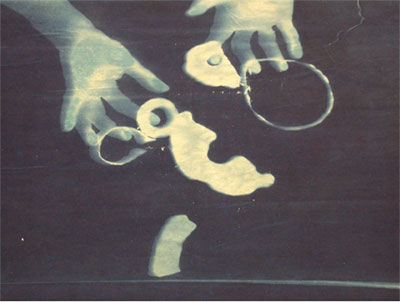

RJ: Let's talk about the cyanotype. For years you've done work using this 19th century photographic technique. Instead of using negatives, you put objects on paper to create photograms. The end result is a ghostly blue and white image. What drew you to this technique? And how you do feel about the resulting image? It's not a high quality photographic image as is possible with digital technology. I would guess that there is something that this image gives you that conventional photography cannot. Could you go into that a little bit?

RH: First, there's this idea about the souvenir, of flipping the hierarchy of what is primary and what is secondary. I am exploring all sorts of offshoots and tangents that have ironically turned out to be more primary than the thing that started it all out. Cyanotype was my solution to the fugitive problem of the diazo process. Cyanotype is very stable and it happens to be blue and white, because of the chemistry involved. The color is a given, which makes it attractive to me. The emulsion, which I brush on, is sensitive to ultraviolet light. What the cyanotype records is the quality of translucence and opacity in a material, and also the distance the material is from the paper and any shadow it casts. The agent in all this is the sunlight. Where my will stops, the sun and time passing take over. Clouds go by, the wind blows, there are shadows from trees, there's the angle of the sunlight. I'm also interested in the idea of vantage point in all of the work that I'm doing. Ray and Charles Eames explored this idea so well in their film Powers of Ten. They showed a couple picnicking on a beach from as far away the outer most reaches of the Milky Way and from as close up as the molecular structure of their bodies. The cyanotypes explore a view of forms that can't be seen with the naked eye. It's not a microscopic view or a magnification. It's a one-to-one ratio of the actual object itself. What is so fascinating to me, and I'll stop doing it when it stops being fascinating, is the complete unpredictability of how the object, sitting on the paper, is going to read in cyanotype. The ones that I save, the good ones, have a sense of deep space within them. They are not flat and two-dimensional. Those are the worst ones. When they are good the objects seem to be sitting back, behind the plane of the paper, making it seem like you could reach in and grab them.

RJ: Yes, it begins to create an atmosphere. And again, it has all these linkages to your use of wax, where you see the surface, and you see beneath the surface. I think you've found a perfect photographic technique for what you're doing. It is curious though, what you said about the sense of depth and atmosphere in the cyanotypes and, in a sense, they're pictorially environmental. You use the words, "reaching into" and it's identical to what it is to walk into one of your installations. So, again I think you've found this perfect technique to mirror and to compliment your three-dimensional work. I think your work in general is like the cyanotype in that it leads to the notion of the romantic. But I'm trying to go beyond romantic. Maybe the words you used "reaching into" say it better.

RH: That's interesting. The constraint I put in front of myself is to not editorialize or embellish, but to reconfigure, to work in a very straightforward manner with the materials I find. And so, that romantic quality, or the poetic quality, or whatever you want to call it, is a residual outcome that is not planned, but that's where the magic lies.

RJ: I agree. That is where the magic lies. I'd like to talk about the work in the show now. Before we get into the specifics of individual pieces, could we talk about what you consider to be the most important unifying factor of an image or form, and its ghost? Somehow, when I think of all these different pieces in the show each has some aspect of that. For instance, the cyanotype creates the ghost of a tree, the white wax balls on the circular forms have been modeled, and then they get cast, creating another ghost. Even the mica-washer drawing is perceived as an ephemeral apparition drawing that depends on environmental lighting to sparkle it into existence. Everything has some kind of echo, and these echoes reverberate throughout the installation in the gallery. They are individual objects, it's true, but they are objects that take their meaning from their relation to the whole. By whole I mean all the objects, as well as the architecture of the gallery, and the viewers' meditating gaze as he or she walks through the installation.

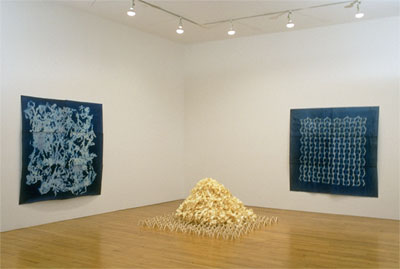

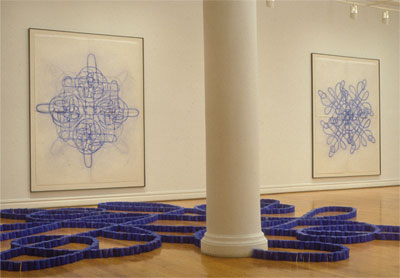

RH: I'm interested in how the idea of the ghost, the echo, can function in things such as casting and repetition. There's a kind of a quotation happening within the work about the work. That is what it all has in common and it all gets back to my earlier description of a minimalist aesthetic, of taking a process and milking it for all it's worth. To continue to extract meaning from something until it's exhausted has involved multiple avenues of investigation. There's not just this one thing, there's this thing and then there's the cast of the thing, and the print of the thing. And the idea of looking from inside out and outside in, looking at something as a fossil, something that is in a state of transformation and the whole idea of inventory. My pieces are not stagnant resolutions but, rather, propositions to be experienced by the viewer as more found objects. The viewer can look at the work and imagine new possibilities. The meat of the work is in the suggestion of what else it can be. That is the thread that runs through the work. These ideas were at work in my Blue Lines installation, years ago, at Lennon-Weinberg. The installation consisted of 4,000 cast plaster cup forms, dyed blue. They were arranged on the floor in huge mandalas, occupying all of the floor space of the gallery. In order to see them you had to walk in and around them. Unless you attached yourself to the ceiling and looked down, you could never see them as a whole. The idea with the cups was that each unit on its own was nothing. They became essential through their contribution to the whole, like words in a sentence, or pearls on a necklace.

That's how I feel about all my work as a whole too. Each piece is just part of an unfolding narrative. I've paid a lot attention to this over the years. I think the way artists' talk about their work says a lot about how they think as artists. It doesn't really matter whether or not they're good public speakers. That's not the issue. What's interesting is whether they talk only about their most recent work? Do they talk about it chronologically? Do they talk about their work thematically? Do they separate the drawings from the painting and the sculpture? How an artist goes about structuring a presentation tells you so much about the work itself. I think it's important to give your public an opportunity to see what you're struggling with and what you're trying to define for yourself, what questions you are asking yourself.

RJ: You've just described what becoming an adult, and aging, is all about. It takes a lifetime to really figure it out. You have to live a life, and you go through a lot of experimentation and, at a certain point, you know enough to really begin to be in your own life, comfortably. And I think that's what an artist does as he or she matures.

RH: That's what is so great about being an artist. You can't convince anyone that it's a good choice to make because it's hard and you have to really want to do it. I tell the students I teach that the payoff is so huge if you keep doing it, because self-exploration is inextricable from your professional life.

RJ: A major breakthrough for me was when I saw that linkage between my life and my art, and realized art wasn't about projecting theories on the canvas, or any of that, it was simply a manifestation of who I was as an individual, a human being. And once you get that, it's so freeing, and it's so expansive. At that point you have to take a different level of responsibility about what your art ultimately is, and also what your life ultimately is. They're inseparable. The other thing that I kept thinking about when you talked about the installation of the work in the show is that you're creating a situation where the viewer can go into that situation and have a parallel experience of his own, or at the very least, get a glimmer of what it is to be you in the world. With your work, I have this image of you walking through the world with all sorts of visual ideas coming towards you. That's where you begin to work. You cast a net for experiences, or visions, or concepts. It's very active, very dimensional, and sensory and, in a way, you're asking the viewer to walk through the gallery in a similar way. The viewer can become you for a little brief period of time, and engage all their sensibilities, and to have a kind of multi-dimensional experience as they walk through it; bouncing from one thing to another thing. And as the images layer, some sensitivities open while others close. And you know, that's so different from how the conventional painter or sculptor would work.

RH: Funny that you use the image of a net to explain what I do. I made a piece recently called Casting a Net. The title refers to a need I had at the time was to find out what was out there, as in where is everybody? I was trying to find my bearings, like a whale using sonar. But what came from that piece was not an answer but more raw material for future work. I had used the cup form again, but this time the little plastic cup bottoms were the marks of a drawing that was push-pinned into the wall to create a dotted line. One viewer commented that it reminded him of the sound made from dragging a stick against a slatted fence. My own children helped me take the piece down. As they dropped the cup bottoms and pins into the joint compound buckets they made more sounds. In Mica and Pins I used a thin plastic template as a guide for the pins. When I pulled the plastic off the heads of the pins, there was sound. The situation resembled a player-piano score. A seed for a sound component was planted. These are the things I caught when I cast my net. It's rarely about finding something that's outside the work; often it's about finding something that's in the work that you just didn't notice before. That's exciting to me. I don't know what I'll do with that. I feel like I could explore it more fully, maybe even collaborate with a musician. I'd like to document the installation of the drawing in a way that it can stand on it's own. I don't know if that would be as an audio or a video piece. At any rate, getting back to the idea of the found, I found new ideas within my own work.

RJ: Moving on to the exhibition itself, what are your thoughts about installing this body of work at Lennon-Weinberg gallery? I am wondering how the space has informed your work. Also could you talk about why you titled the exhibition Multiplying the Variations?

RH: I took the title from a passage in the book The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard. It's from the last chapter, The Phenomenology of Roundness. To paraphrase, he wrote: Van Gogh wrote: Life is round . . . If we submit to the hypnotic power of such expressions, suddenly we find ourselves in the roundness of this being, we live in the roundness of life, like a walnut becomes round in its shell. A philosopher, a painter, a poet and an inventor of fables have given us documents of pure phenomenology. It is up to us to use them in order to gather being together in its center. It is our task, too, to sensitize the document by multiplying its variations. My choice of that title makes reference to the multiplicity of found materials I work with, to the variations I subject them to, and to the sensitizing of the concepts that occurs as a result. It was a title that seemed to fit what I am doing, perfectly. As artists we consciously or subconsciously sensitize other artists works too, by multiplying the variations on our own terms. In that regard it is important to understand the continuum you are a part of. I am interested in many artists, such as Jim Turrell, Robert Irwin, Christo and Jean Claude, Catherine Murphy, Chuck Close, Eva Hesse, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, all artists whose work approaches magic for me. There is a dialogue going on between artists at all times, even if only on a subliminal level. To answer your question about how the space informs my work, it's in terms of scale mostly. It has to be a consideration. The beauty of this space is that there are three spaces that allow for works of different scales to be shown. It is possible to feel like you are discovering the work in the show, much like in a museum. In a one person show the work needs to read as a whole, but it's an incredible luxury to isolate the pieces from each other and have each piece experienced on it's own terms. I'm going to put smaller drawings and cyanotypes in the entry gallery in hopes that they will read as treasure maps for the work that will unfold in the main gallery. Upon exiting the gallery, the viewer might experience them as souvenirs, or distillations of what they have seen. The installation allows for a circular reading of the work, as opposed to linear, which is also the underlying theme of the work.

RJ: I think your sensitivity to the qualities of the specific rooms is what allows for the idea of circularity to emerge.

RH: I've grown to appreciate any exhibition space as an opportunity to create a narrative. Progression through a space may seem seamless, but how you organize the work does contribute to the meaning of the work. Walking through a space is analogous to turning the pages of a book. Some of my work is site-specific, but this work is more site-sensitive, which is an important distinction that the artist Robert Irwin makes. I will be making a site-specific piece for a museum exhibition in Budapest. I will have to build a model and work in miniature to figure out what I am going to do. My interest in site-specificity has been hugely influenced by Lucy Lippard. She talks about art that concerns itself with a sense of place in the Lure of The Local, and calls on artists to develop a keener sense of awareness of the cultural and social nuances that inhabit and inform one's work, and ultimately determine its meaning. Thomas McEvilley also talks about these ideas in his essay Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird, which has served as a kind of check valve for me for understanding what is going on in anyone's work, not just my own.

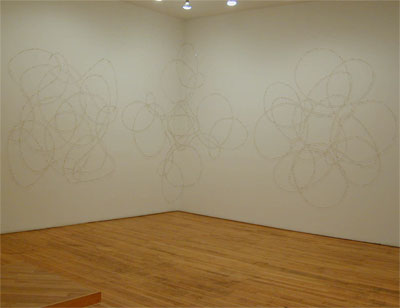

RJ: Mica and Pins, the mica washer drawing in the big room, is the most ephemeral piece in the exhibition. It flickers in and out of existence. It's a drawing that you can perceive from a very long distance, but it's also a drawing that compels you to move towards it, and to have an intimacy with it. Could you talk a little bit about how you made that drawing, and where the feeling of drawing comes into play for you as the maker?

RH: First of all, my drawings are really a hybridization of sculpture and drawing. There is a great deal of physicality in my drawing that brings it into the realm of the object. I'm really interested in how the drawings can be a thing and a non-thing alternately. A more accurate way of looking at my drawings might be as events. I found the mica washers in a dumpster in New York. They were strung on a long string and looked like a drilled tubular core of mica. The translucency of the material spoke volumes of potential. The washers hang from the heads of thousands of straight pins pushed directly into the wall. The act of drawing takes place when I push the pins into the wall, following a template of a geometric configuration. I'm engaged in making a line that's correct, in terms of my own sense of proportion, scale, and curvature. There is a right way, and a wrong way. It has taken me a while to figure out how much this sense of accuracy determines the feeling of the lines in my work. When I have other people install my work I have to face the agony of the inaccuracies. This is one of the few areas in my work where there's a sense of erasure. Sculpture is very unforgiving in many ways. If you get it wrong you often have to start over. I savor the fluidity, spontaneity, and forgiveness in drawing. The whole idea of approaching perfection, which was the name of a group show I was recently in, describes work that aspires to accuracy, however subjective the standards are. Despite my efforts to correct the mistakes, there are always subtle traces of this struggle in the work. I think that's a good thing, where it fails. That's where the energy of the drawing resides for me.

RJ: There is poignancy in your exploration of the boundaries between traditional drawing and sculpture. And I'm thinking about traditional drawing having the capacity to create a kind of illusionistic, spatial dynamic while your mica washer drawing creates a very real, three-dimensional space. You have substituted the paper with the wall.

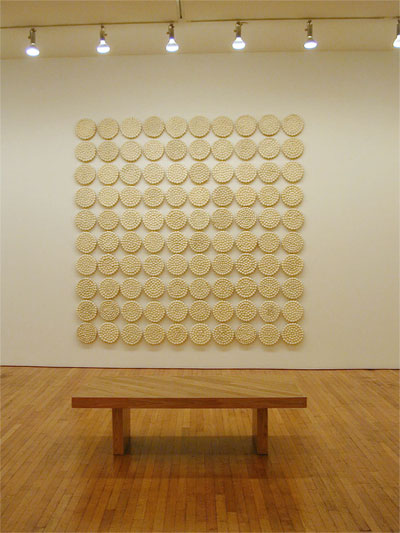

Could you talk a little bit about Against the Wall, the wax ball piece?

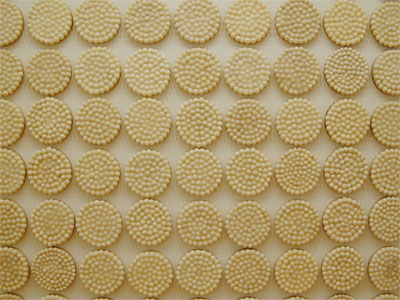

RH: The piece is obsessively labored over. There are about nine thousand, one inch, wax balls, arranged on circular discs of Finland Plywood which I found in a manufacturing surplus store in Berkeley. Ironically, this is the same material I used in my early freestanding sculpture, which I salvaged from the dumpster of a box die company that occupied the ground floor of my studio building in New York. Another strange coincidence is that the diameter of the plywood discs is the same diameter of the linted scotch tape rolls I prepared for add lint to scotch tape rolls. re-roll. the coils are now ready to serve. The wax balls look like a kind of pastry that's just come out of the oven. They are installed on the wall to create a 10 ft. grid, which reads as a blank slate. It's the notion of nothingness that I'm interested in. An earlier impulse would have been to use that surface for another layer of imagery. Sitting somewhere near it, either in front, or off to the side, in an opposing corner, or across the room, will be the same number of discs cast in Hydrocal. As with previous work there's a feeling of inventory and possibility. One could imagine that the wax pieces evolved out of this pile, or maybe the pile represents a future incarnation, fossilization. One material is the echo of the other.

RJ: You once said that you thought your touch was invisible. I think the opposite is true. Your signature mark, the sensitivity of the touch of your hand is central to your work.

RH: I'd like to think that the work I am making was already here, and that I have just facilitated its visibility. I know the quality of the hand-made bleeds through and leads to me as the maker. If nothing else this position does help alleviate some of the crippling feelings that come into play when one asks the inevitable question, what am I contributing to the world?

RJ: I don't think you should underestimate the power of the handmade. There are many monochrome painters who demonstrate its power. Once you train your eye to actually look at their paintings you can pretty easily tell the difference between each one, simply by the touch of their hands. Touch is a big part of your work too. It's a touch that has always been there. I think it's a quiet, subtle type of signature that informs all of your work. It is highly nuanced and evolved in the sense of placement also, and that's the heart of your sensibility. It is parallel to what a painter would go through to develop his or her own way of working or signature. Your work is three-dimensional and experiential. The sense of touch is in everything, the sense of placement is in everything. The notion of the work being fully sensory and three-dimensional is very different from painting which is two dimensional, and perceptually nuanced. It is very moving to me to see that quality in your sculpture. I think that is your signature, and is at the heart of the work.

RH: It's hard to know what you've done until you've done it. Merleau Ponty said it beautifully in his essay Cezanne's Doubt: Conception cannot precede execution. There is nothing but a vague fever before the act of artistic expression, and only the work itself, completed and understood, is proof that there was something rather than nothing to be said ... a successful work has the power to teach its own lesson. There can be purposefulness without clear intentions. I am purposeful making the elements for my pieces. It is that purposefulness that is the determining factor in a work becoming anything or not. It's like a scratch that has to be itched.

RJ: I think you are describing an intimacy one has with the work while it is in progress. It's so utterly yours and private. You seem to have built this intimate form of conversation into the work. Could you talk a little bit about Dissipation, the cotton-batting piece that goes from the wall onto the floor?

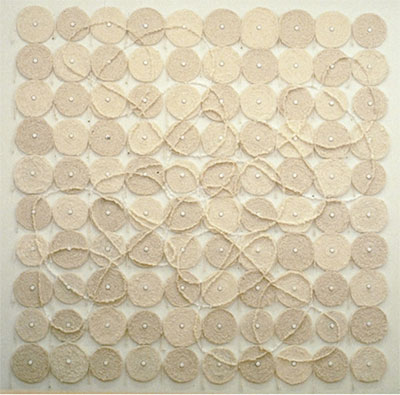

RH: The cotton-batting piece is very similar in spirit to the wax ball piece in that there's a replicated, circular form; this time the replicated form is one-inch, flat, discs of cotton, which I found in a cotton-batting factory in Brooklyn. The owner gave me the off-cuttings of shoulder pad material, and I tore it up and made the discs.

The discs are clinging to, by friction only, sheets of paper that have more cotton affixed to them. I played with this piece a lot. The process of making it was open-ended to the point of absurdity. After devoting hundreds of hours to making the parts I still had the problem of what to do with them. First I made a curvaceous line that moved around itself. Then I made a tree with big branches reaching out. I wanted to work with an idea of growth and evolution, particularly my own, which is one of the subtexts of the exhibition; the revisiting of materials and processes that I was engaged with years ago, looking to bring them back to life. I was sidetracked by the desire to represent something literal. It was feeling very uncomfortable and very unnatural. What I ended up with was more of a situation with the dots, rather than any type of depiction. I piled them all up on the floor and arranged them vertically in a compressed, rectangular column, rising up in the big, rectangular space of the gridded cotton sheet. The dots start to disperse and dissipate, and then disappear. There's a kind of upward motion, like bubbles floating up, like effervescence in a glass of seltzer. Without being overly descriptive, this solution did a better job of referring to the idea of growth and dispersal.

RJ: Can you pinpoint exactly why you started to search for something literal to begin with? It would answer the meaning question in a really obvious way, which seems like a natural impulse, if part of your question is what is the meaning of all of this? Meaning that is generated through a literal narrative grounds the work and is easily understandable by the ordinary viewer. Is this something that you keep coming back to, or is that impulse particular to this piece?

RH: I look at those episodes of trying to be more literal as unfortunate detours. They're not productive. It's a kind of second-guessing of my instincts, and represents a distraction from what is driving the work. It usually starts with being overly concerned with what a viewer will think. I know that it is a ritual that I have to go through. I forget who I am. I forget what I care about. I think all artists must feel this way, but not everybody talks about it. We all step outside of ourselves to see what we could do differently. Sometimes you have to stray to find out that there was nothing wrong with where you were. Walter Benjamin said, to understand something is to understand its topography, to know how to chart it, and to know how to get lost.

RJ: I think that's important to at least mention, considering you've been making art for almost thirty years, that those moments of doubt are still part of the process.

RH: Hopefully it's not catastrophic. If that were the only feeling you ever had when you made your work it would be torment. A labor ethic comes into play, which leads to a need to prove to oneself that one has worked hard enough on something to call it worthwhile. This ethic makes trusting something that pops out effortlessly and perfectly the first time difficult to trust. That is probably one of the most positive aspects of my working in cyanotype and drawing, where there is at least the opportunity for something instantaneous to occur, and to count. It's important to have something that you do in your studio where that can happen.

RJ: The gallery has a back room that has natural light. You used it so well in One Hundred Feet of the Sweet Everyday, your installation of cyanotype with images of airborne shopping bags. That was one of the few times I've seen that room used so beautifully. Could you talk a little bit about how you imagine your new work in that room?

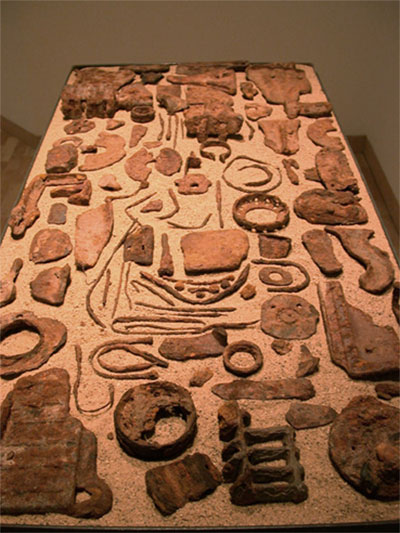

RH: I will install a piece called Beach Debris that consists of ten 9' long panels of cyanotypes of my hands dropping fragments of rusted stove parts that I found on the beach. The actual fragments will be resting in bed of sand on a simple steel pedestal. It resembles a 19th century museum presentation of an archeological dig. The variegated blue striations of the cyanotype unintentionally refer to what the debris tumbling in the tide might look like. The room has a kind of beach light, so it seems fitting to install the piece there. The piece doesn't really fit in terms of the idea of the circular motif, but it does fit with the idea of the handmade, the found, and in the repetition occurring within it. As with all of the work there is a background of collecting a material and transforming it into something else. It's the most representational piece in the exhibition.

RJ: I'm curious, did you make the cyanotypes of the beach debris with natural light?

RH: Yes. I made them in Cape Breton where I have a summer place. I exposed the paper in a huge clearing in front of our cottage. Each section took 15 minutes to expose.

It's funny to me that the work seems so serene when, in fact, the process can be quite frantic. In making the piece I was trying to keep things from blowing away, sometimes forgetting about them, and running back and forth over a course of days. I love learning about these conditions in other artists' processes, about the peculiarities of their materials. The person who makes the work can never really enjoy the finished product without remembering the conditions surrounding its making.

RJ: Maybe after a number of years you can. In general, all of this work has a meditative quality, and it has a kind of calmness, and serenity to it, and I do think that's fairly consistent with everything in the show. It's really interesting to have you talk about the turmoil involved in creating it. Will the tree cyanotypes from your installation Clearing be in the show?

RH: I'm not sure. I considered using the tree cyanotypes to drive home an idea about the synapses of the brain, to show how all of these seemingly disparate works, made of different materials and in varying scales, are connected by threads of information and thoughts. And there is also the parallel to reaching out from a core. In the images of my hands dropping the beach debris there is a kind of reaching out. There's also the release of matter into an unknown space in the arrangement of the cotton discs. Everything in the exhibition has its root in something found. And it's not specific to where it is found. The finding in my work takes place on the street, in industry, and in nature. As I mentioned before, I often find things in my own work. The tree images fill out the scope, anyway, of how the found operates in my work.

RJ: When you say that the tree images are like dendrites, then you could also think about the roots of the tree and how they look almost identical to the branches of the tree in your cyanotypes. This is another example of seeing beneath the surface that happens in much of the work, especially the wax pieces. When I'm looking at the tree images, I think about what's below ground, which is what I think about when I look at the wax ball piece. We haven't talked about the wax and string piece, The Shape of Things to Come. This is the piece that seems to draw on your earlier work in wax and also taps into your interest in chance as a working constraint.

RH: The chance-derived string configurations embedded in wax are propped up on cast wax cup forms, which sit on a mirrored surface. The shapes have an anthropomorphic quality, and generally invite associations with other things in the world, including other art. The forms feel animated, as if passing by like so many clouds. It's the smallest piece in the exhibition, but also the most complicated. As with all of the work, I hope to provide enough of a kind of template for viewers to superimpose their own wishes, or dreams, or sense of familiar experience upon. I am trying to present not so much my vision, but an opportunity for others to have a vision through the work. I had a flash of my work being like a strainer, or a filter, in it's physical appearance. There is air and space, a kind of filminess, and a quality of perviousness, as opposed to imperviousness. I'd like the work to provide a way for catching, trapping, or holding thoughts that might ordinarily just slip through. All of this requires subduing a certain amount of my own voice to create that feeling. Maybe that's the key to all abstraction, truthfully.

RJ: So many people who look at art aren't comfortable enough with it to let it register. They've approached it as something they don't do or can't do, which makes it feel foreign. Children are the exception. They see things for what they are. I think artists often draw on their early years of experience for their inspiration. As we grow and become more a part of the society and culture, perception becomes more and more filtered. And I think it's very hard for an artist to create something that makes it though the filters. Your work seems to open up a kind of infinity of possibility. The viewer is invited to contemplate the possibilities, which can lead them into deeper perceptual possibilities. The work is totally expansive and hopeful.

RH: Hopeful?

RJ: Yes. It's very hopeful in that it presents the possibility for a human being to perceive and interact, to be in the mystery of what life is, and what emotion is, and what feeling is. And to escape the normal kinds of definitions of all those things, I think that's exactly what you're doing.

RH: I hope it's what we're all doing.

RJ: Well, we're all trying to, Robin. I think it is one of the things that abstraction can do. Abstraction does have the potential to make the invisible visible and to make you feel feelings that aren't even locatable in your normal feeling structure. Looking at art can warp time and space, even just seeing it in a gallery setting. That's a miracle of sorts.

Is there anything else you'd like to say, Robin? It's a good way to end it, isn't it?

RH: It is a good way to end. We have caught our thoughts in a net, and now they are here for others to find and sift through.

October 2004

About the Artists:

Robin Hill Robin Hill is a sculptor and Associate Professor of Art at the University of California, Davis. Her work has been exhibited extensively both nationally and abroad. Her work is in numerous private and corporate collections, as well as in the collections of the Richard L. Nelson Gallery & The Fine Arts Collection, the Fogg Art Museum, and the UCLA Hammer Museum. She is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Artist Fellowship in Sculpture, two Pollock-Krasner Foundation Fellowships, and two New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowships. She is a former fellow of the Davis Humanities Institute for her research on the subject of The Poetics and Politics of Place. Recent solo exhibitions include, Multiplying the Variations, Lennon, Weinberg, Inc. (New York) 2004 and at the University Art Gallery, California State University, Stanislaus, 2006; Kardex, another year in LA (Los Angeles), 2006; Drawing the Line, Don Soker Contemporary Art (San Francisco), 2007; upcoming: Robin Hill, Jay Jay Gallery (Sacramento), 2008. A catalog was published on the occasion of her exhibition at CSU Stanislaus entitled Multiplying the Variations, with an essay by poet and critic Raphael Rubinstein (ISBN: 0-9773967-6-2). For more information:

www.robin-hill.net

Ron Janowich is a painter and Associate Professor at University of Florida, Gainesville. His work is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Tate Gallery, London, U.K.; Cleveland Museum of Art, OH; Harn Museum, Fl. and numerous private collections. His work is published in various books including History of Modern Art by Arnason H.H., The Aesthete in the City by David Carrier, Beyond Piety by Jeremy Gilbert Rolfe, and Art Speak by Robert Atkins. He is the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Artist Fellowships in Painting. He recently co-curated two exhibitions: "Thinking in Line" at The University Gallery, Gainesville with John Moore and "Synthesis: Experiments in Collaboration" at the Axel Raben Gallery, NY and Lafayette College, PA with Merijn van der Heijden, and at Pace University with Merijn van der Heijden and Will Pappenheimer. For more information

www.arts.ufl.edu/art/Personality/Faculty/janowich.asp

Citation Styles:

|

|

|

|