|

Harold Marcuse Other Voices, v.2, n.1 (February 2000)

Text copyright © 2000, Harold Marcuse, all rights reserved. Illustrations (excepting "The Point of View Diner") © Jim Mendenhall, all courtesy of Simon Wiesenthal Center-Museum of Tolerance. Additional photographs of the Tolerancenter and Holocaust museum are available at the Simon Wiesenthal Center website. In the 1990s, three elaborate new Holocaust museums were opened in the United States—in Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and New York City. Each one takes a very different approach in its attempt to ensure that the Holocaust is not forgotten. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington sets upon the power of laboriously obtained and fastidiously displayed original relics. In New York, the "Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust" sets the Nazi Holocaust into the longer-term context of Jewish life, highlighting artifacts of Jewish culture produced before, during and after the Holocaust. And in Los Angeles, the "Beit Hashoah—Museum of Tolerance" attempts to make the Jewish Holocaust relevant to Los Angeles' largely non-Jewish and non-white population by setting it in the context of modern racism and genocide. It differs from other Holocaust museums and even most conventional historical museums in other important ways as well. It openly declares its intent to use history to teach lessons of tolerance and responsibility to its visitors, and it unapologetically employs modern entertainment technology to appeal to young visitors and manipulate their emotions. The latter aspect especially has made the Museum of Tolerance, as it is commonly known, far more controversial than most museums. Regardless of the criticism, however, a veritable flood of visitors which has not abated since the Los Angeles museum opened in March 1993 indicates that it succeeds in packaging its message for a mass audience. The waiting period for tours by school groups is often as long as six months, and individual visitors pack the museum on weekends. It has even become a kind of public service: Los Angeles police are regularly brought in for day-long sensitivity training sessions, and the sentences of convicted gang members sometimes include participation in its educational programs. Given such popularity, it is all the more important to examine critics' two main concerns: first, they claim that the Los Angeles museum, in order to appeal to a broad audience, simplifies its lesson so much that it is essentially void of worthwhile content, if not downright "misleading" or even "dangerous." Second, they argue that its entertainment format and appeal to emotions are not suitable for teaching lessons about complex, intellectual issues. A tour of the museum is the best place to start a quest for the answers to these questions. School classes enter the polished façade of the imposing but modestly proportioned granite and glass building from buses parked at the curb of the commercial street outside, while individual visitors ascend in an elevator from its cavernous parking garage. After purchasing a ticket stamped with an imminent departure time, they congregate at the top of a Guggenheim-like spiral ramp that leads to the main exhibition floor below. A docent ascends at preset times to lead them down the spiral, where the 2 1/2 hour guided tour begins. Originally, all groups were supposed to go through the Tolerancenter first, but because of the unanticipated popularity of the museum—averages often top 6000 people per week—some groups are taken through the Holocaust tour in the Beit Hashoah first. The Tolerancenter begins with a walk down an incline through a slide show of people of different races happily participating in outings, parades and such like. The visitors' shadows gliding across the images indicate, the guides explain, that we, too, are part of this "Celebration of America." At the bottom of that incline a perky "Manipulator"—a glib TV talk show type whose face appears on different screens mounted in a boxy, oversized human form—greets us.

"Hey, there! You look like average people. I mean, you've gotta be above average or you wouldn't be in a museum in the first place, right?" From another screen: "Of course, we all have our limits. And we should. There's no reason to accept the lousy way certain people drive, f'r instance, not to mention how the you-know-who's do business. But I can tell you're not like them!" After insinuating our arrogance and prejudice, he nods towards two closed doors, one marked "PREJUDICED" which lights up in alarming red neon, the other "UNPREJUDICED" in calmer green. Our flesh-and-blood guide asks us to choose one, but almost immediately informs us that the "not prejudiced" door is locked, and that we should think about what it means to enter under the epithet of prejudice. This trick, our guide tells us, underscores that everyone harbors hidden prejudices.

This choice that is not a choice prefigures another forced self-selection in the Holocaust exhibit, two tunnels labeled "Able-Bodied" and "Children and Others." There, however, both are open and lead directly from a realistic concentration camp gate into a pseudo gas chamber. We will soon see another image that reminded me of this two-doored choice: drinking fountains labeled "Whites only" and "Colored." The replication of such images is a powerful way of emphasizing the commonalities across historical situations.

On the wall inside the double doors we read the slogan "The potential for violence is within all of us." There is a generous sprinkling of similar maxims throughout the museum—"One Nation, Many People", "Freedom is not a gift from heaven. One must fight for it every day", "Hope lives when people remember." They remind me of the pro-socialist slogans that once dominated the public spaces of Eastern-bloc Europe ("Work together, plan together, succeed together"; "Build socialism—for a humane future"). Docents leading school classes take a moment to read the "potential for violence" epigram aloud and link it to the message of the doors. My coincidental group of tourists had no time for that, since we were already running late—the Manipulator had begun speaking before our docent had us at the bottom of the ramp, and the doors darkened again before we went through. While docents guide school classes through a few selected stations, my tourist group was invited to explore the dozen or so exhibits and films at our leisure. Loud dialog emanating from a TV screen near the entrance grabbed my attention first. The exhibit "Me...A Bigot?" exemplifies the Tolerancenter's media-based approach—and some of the problems arising from favoring form over content. A one-minute skit repeats continuously. It begins with a white doctor at a cocktail party exclaiming: "Guess who moved in next door?" A black businessman's face appears—"I mean, right next door." A series of people—Asian male, bejeweled white matrons, young Black woman, etc.— pass in quick succession. "You know what they're like—dirty... pushy...greedy...sneaky...lazy...always living off our taxes...always bragging about their...money...religion...better education...." The next sentence is begun by an Asian man and continued by a Hispanic woman: "Sure wouldn't want my daughter...son...sister..." "...marrying one of them," concludes the elderly white woman. A white male begins the final exchange: "But don't say anything...They're my best customers...A lot of them are my patients...neighbors...I wouldn't want people thinking I'm prejudiced...racist...a bigot...Bigot...BIGOT" echoes through the exhibit hall as the faces on the screen, in turn, look up in surprise. This flash-by cocktail party dialog is probably intended to underscore the ubiquity of prejudice among all ethnic groups. However, it sends confusing signals. Although its overt message of ubiquitous prejudice is obvious, the presence of such a broad mix of people at one high-class social event signals that prejudice has less to do with race than with class. Even if the exhibit intends to show black or Asian visitors that they, too, harbor prejudices, what it really reveals are the class biases of the rich. What might high school students from poorer areas take away from such an exhibit? The museum has not systematically investigated reactions to its exhibits, but I noticed that docents usually move their groups quickly past this TV skit.

Instead, most school groups are taken right away to a new $1.4 million high-tech "Point of View Diner" which opened in February 1998. It replaced several less effective original exhibits, such as three video-headed mannequins labeled Joe Cool, Mr. Normal, and Miss Uptight. They were supposed to allow visitors to "follow on-screen thought processes which reflect the influence of advertising and the media." But, as one docent told me, "No one knew what the heck they were talking about." Critics were correctly skeptical of the effectiveness of such misguided early exhibits, which also included a "Whisper Gallery" of racial epithets. The red vinyl seats of the Point-of-View Diner are fitted with 1950s-style silver jukeboxes containing touch screen computers and telephone earpieces. In one of its scenarios, a news flash on the main TV over the bar shows the scene of a crash in which a drunk teenage driver "Charlie" and his girlfriend "Debra" hit a car carrying a father and his 10-year-old daughter. The drunk driver died at the scene, the young girl is in critical condition. Follow-up news flashes three, seven and ten days later inform us that Charlie had a long-standing drinking habit, that the 10-year-old died of her wounds, and that the accident prompted a discussion in Los Angeles about how to curb teenage drinking. The docent then asks viewers to pick a number from one to five indicating the degree of responsibility they assign to Charlie, his mother, his girlfriend who bought the booze, and the store owner who sold it. The tabulated results are shown on the main TV, for my group: 22%, 15%, 29%, and 32% responsibility. (The percentages are presumably tenfold numerical averages of the assigned values.) Then we are told that we can use our touch screen and earpiece to "interview" Debra, Charlie's mother, and the store owner—we select from a list of questions, and listen to the videotaped answers. The questions focus on why they allowed Charlie to continue drinking, and whether they feel responsible. When asked the latter question, each one disavows all responsibility. The mother, for instance, blames Debra, while the store owner asks, "Don't you think the responsibility lies with the kid who got drunk?" Again we are asked to gauge responsibility. This time the results are 13%, 30%, 27% and 27%. After the interviews, my group lessened the blame on Charlie and the store owner, and heaped it onto Charlie's mother—but I could only determine that later because I had jotted down the numbers. The main TV concludes with images of the homeless, child labor, racist crimes, war victims in Bosnia, and Nazi prisoners in the dock at Nuremberg. The narrator sums up: "If we all assume responsibility when we witness evil, we can change the world." This exhibit reflects a maturation of the museum's conception since its 1993 opening. It goes beyond attempting to make us recognize our own prejudices, and tries to move us to feel responsible and take action. Another multimedia exhibit "Crime and Punishment" is planned, in which visitors will serve on juries in a mock courtroom. They will pass judgment on collective crimes such as starvation and genocide. Role-playing is often used as a teaching tool in schools, and kits with ideas and props are readily available. These new exhibits can be seen as sophisticated role-play kits far out of the reach of individual school budgets, and thus worth the price of a visit to the museum. The docent follows up with a brief, skillfully-led question-and-answer session about teen drinking in the U.S. Her conclusion: each individual is responsible. Having lived for over a decade in Germany, where teen drinking is not prohibited nor nearly as big a problem, I wonder whether I should bring up social mores as a possible partial cause of the problem. But that is a complex and controversial issue similar to gun ownership ("guns don't kill, people do") and legalization of marijuana, and would weaken the powerfully-felt message these teenagers have just experienced. On the other hand, this type of simplification is precisely what the museum's critics find fault with. Visitors continue down a hall with a time line along one wall. Part of the facing wall is split into 16 video monitors, on which the film "Ain't you gotta right" repeats in 10-minute intervals. This fast-paced split-screen montage shows scenes from the 1960s civil rights movement, including footage of segregated buses and restaurants, police beatings, and passages from Martin Luther King's "I have a dream" speech. Nearby, an 8 1/2 minute film—it is precisely timed with an LCD timer—on genocide is shown in a small theater at regular intervals. This film, too, was changed in the 1998 remake. The original film flashed gruesome scenes from historic examples of mass murder across three screens in rapid sequence: the murder of Armenians during World War I, Pol Pot's butchery in Cambodia in the 1970s, and the deaths of native peoples all over Latin America due to "massacres, government indifference, starvation and disease." My most vivid memory from the old film is of severed heads stuck ghoulishly on pikes. The new film begins with the end of World War II, which, it tells us, was not the last instance of mass slaughter. Horrifying scenes from Bosnia and Rwanda in the 1990s show how the "violence that inevitably follows hatred" has persisted to this day. Viewers are unlikely to forget the images of bloody corpses on Yugoslavian streets or desiccated corpses in the African sun. The concluding sequence begins with examples of racially motivated violence in the U.S., Russia, Germany, and Israel, and ends with an American teenager being inducted into the Klan on her sixteenth birthday. The film suggestively links mass murder throughout the world to individual actions in the United States. After the genocide film visitors enter the waiting area for the Holocaust section. When the doors of the Beit Hashoah swing open, an hour-long, computer-controlled odyssey through fourteen stations begins. In the first three dioramas we listen to diminutive plaster mannequins introduced as a balding "historian," a female "researcher," and a slick "set designer" discussing how best to design a museum about the Holocaust. In the sets on the 1920s, antisemitism is heavily emphasized, while economic causes are given only a passing reference. The role of big business in helping the Nazis to power is not even mentioned.

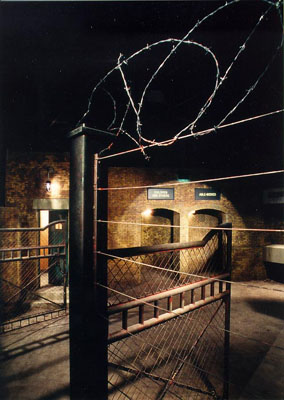

In contrast to the lavish attention devoted to designing evocative sets, less effort was taken to ensure the accuracy and meaningfulness of the narration. The German hyperinflation of 1923, when money was worth "less than rags," for instance, is conflated with the depression after 1929, when money was very dear. Thus the actual economic conditions preceding Nazism are turned on their head. Does that matter? Given the relative brevity of the entire museum visit, students are highly unlikely to notice, and even if they did, this is a topic that requires substantial discussion before it is understandable. However, this trivial mistake does point to a deviation from the Beit Hashoah's conception. The Holocaust museum recapitulates a canon of events that cannot possibly be absorbed during a visit. It would have made more sense to have an even more issue-oriented approach, with dioramas addressing the economic roots of fascism or the role of bureaucrats, for instance. As we will see, the 1935-41 station, a movie theater which interrupts the dioramas, has recently been changed to promote a more thematic approach in addition to the chronological narrative. Set by set we are advanced through the 1930s and 40s by spotlights darkening as others brighten to illuminate the next display along the corridor. One reviewer likened the experience to "Disneyland, but with content." As a fund-raising brochure for the museum described it, this is an "innovation in museumology, a series of exhibits that tell their story without written text." Visitors are to "experience a living social document." 1 At the end of the hall, another set of doors swings open, and our docent ushers us into a small theater with large video screens on the front and back walls. Originally, documentary footage in sixfold parallel projection fast forwarded visitors through events from 1935 to 1941. In 1998 the film was changed to hammer home a message: the mass executions were committed by "ordinary German people," indeed "ordinary men" in mobile death squads, who had been "ordinary people" leading "ordinary lives" prior to their participation in genocide. This message amalgamates widely-debated interpretations put forth by Holocaust scholars Christopher Browning in 1992 and Daniel Goldhagen in 1996. After five film minutes we are spewed out into the dark corridor again, where we can insert plastic identity cards we received at the beginning into computer terminals. A picture and two paragraphs about the early life of our Holocaust alter ego appear briefly before the next station lights up. We turn to peer into a mock-up of a miniature conference room which looks as though its participants had just walked out for a moment, leaving their papers behind. Voices read a script discussing how best to dispose of millions of Jews, while ghostlike images of mass executions are projected onto invisible screens above the table. It is a representation of the so-called Wannsee conference of January 1942, known because a copy of the summary document was found among the files of a government ministry. This exhibit exemplifies the advantage of the museum's novel approach. A museum official explained that in the 1970s predecessor to this exhibit, the summary document was "on the wall and no one ever looked at it." Now, for about four minutes, visitors are exposed to dialog that suggests how unfeeling bureaucrats may have discussed genocide. Again, however, emotional appeal is given precedence over historical accuracy. Aiming at maximum effect, the narration contends that the genocide of the Jews was "launched" at the conference. Actually, SS division chief Heydrich called the meeting merely to inform the various government ministries that he was now in charge of the genocide, which had begun months earlier. The ambience of the final stations becomes markedly harsher. The carpeted floor gives way to naked concrete and simulated ruins. Our plaster guides ask and answer the right questions for us. After they discuss whether Jews went to their deaths "like sheep to the slaughter," we move to a diorama about resistance in the Warsaw ghetto. We pass through a scaled-down replica of a concentration camp gate and end up in front of a map and tiny model of part of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, where three tin-soldier-sized prisoners hang from gallows. Our flesh-and-blood docent greets us and rattles off a few sentences about Auschwitz before ushering us into two ovenlike brick tunnel entrances, labeled "Children and Others," and "Able-Bodied" (see above). The arched doorways are designed to resemble crematorium ovens.

No physical Holocaust installation ever looked like this or offered this choice, but the bodily experience of being forced to choose helps us to imagine the victims' experience. Both tunnels open into a reinforced concrete "Hall of Witness" reminiscent of what a gas chamber might have been like. Instead of shower heads protruding from the ceiling, however, eight video monitors glare down as we file in to take our places on a cement bench. We hear horrifying stories of barbaric cruelty, then edifying testimony of resistance against overwhelming odds. Actors read the scripts, so that the accents of the survivors do not distract the visitors. A docent appears at the far end of the chamber, calling on us to exit so that the next group can come in. The parallel to the assembly-line method of genocide may be coincidental, but it does underscore the subliminal experience of being powerless pawns on an assembly line. Outside, two stations cover the liberation of the camps and present a gallery of the righteous, such as Oskar Schindler and Chiune Sugihara. A perusal of the comment books in the foyer reveals that the overwhelming majority of visitors young and old who recorded their remarks were very moved by the exhibtry, and favorably impressed by the museum as a whole. The large number of teachers who raise the funds to return with new classes year after year indicates that they find the experience a useful complement to their lesson plans. I spoke with a language arts teacher who was returning for the third year. She organized visits by all of the eighth-grade classes in her school, which had been reading the Diary of Anne Frank and other Holocaust books that year. Her school dedicated a whole day to a follow-up discussion of the museum visit, which she considered an extremely valuable augmentation to the curriculum. However, such positive responses contrast sharply with the harsh criticism academic reviewers have leveled at the museum. Nicola Lisus wrote one of the first sophisticated critiques of the museum, which influenced many later reviewers. Her summary of her nuanced analysis is worth quoting in full:2

This critique is erroneous on two levels. First, the museum does not make several of the assumptions Lisus and Ericson impute to it (there are several others embedded in the "two" they name). It does seek to make an emotional impact on its visitors, and it does presume that multimedia formats are an effective means of making that impact on its target audience. Both that goal and the means of reaching it are pedagogically reasonable. However, the museum does not assume that there will be a "clear and direct translation into understanding...for purposes of genocide prevention." As its seminar and outreach programs show, the museum is highly conscious of its limited ability to foster "understanding" in a three-hour session. Accepting that limitation, the museum seeks to maximize its effectiveness as a focusing point in a much larger process. And even if the Holocaust origin of the museum and some of its films emphasize instances of mass murder, there is no evidence to suggest that its direct goal is to "prevent genocide." Promoting tolerance and acceptance of responsibility are far more modest and reasonable goals. Lisus' and Ericson's reproach of monocausality is also manifestly incorrect. We have already seen that although the museum prioritizes intolerance as a cause of potentially genocidal behaviors, and although it neglects some other contributing factors, it by no means limits itself to one cause. The Wannsee diorama (as well as the updated 1935-41 film) squarely address the role of bureaucrats. Apathy is mentioned in several exhibits, and highlighted in the new Point of View Diner. The role of obedience to authority is not made explicit, but I wonder how many "causes" visitors can be expected to absorb in three hours. Let us examine the two actual assumptions underlying Lisus' and Ericson's critique: the museum's presumption that its target audience is disinterested, and its consequent reliance on media formats with emotional instead of intellectual appeal. From Los Angeles' large, ethnically diverse population, the museum's designers chose generations and ethnic groups with little or no knowledge of the Holocaust as their target audience. They decided to use a typical teenager as their model visitor. In the words of museum director Gerald Margolis: "If you can communicate to a bright 17-year-old, you have communicated to everyone." He explained why he thought a TV format would be the most effective means of reaching such visitors: 3

Although this offhand formulation is condescending and exaggerated, it is probably safe to assume that most of the museum's visitors spend more time in front of a TV set than reading books. In spite of the overwhelming reliance on fast filmic formats and artificial representations instead of artifacts, the museum is not a TV set. It is a physical space with many additional possibilities. In fact, Hier rejected an early suggestion to design the museum as a conventional cineplex, with separate theaters addressing issues such as "justice" or "stereotypes." That would have been too passive an experience. Thus arose the various interactive features of the Tolerancenter, and the pseudo-realistic staging in the Beit Hashoah.4 Even if the use of media is justified, why does the museum exclude genuine artifacts from its main exhibition space? And what does it lose by doing so? For the first 2-1/2 hours of the standard 3-hour tour, visitors do not see a single genuine historical object. This was a conscious decision by museum's designers. As museum expert Robert Sullivan, who was a consultant for the project, explained: "Instead of saying: 'We've got a collection to show,' they've started from: 'We've got people to change.'"5

However, even if the primary tour of the Beit Hashoah—Museum of Tolerance completely dispenses with artifacts, visitors are given an opportunity to examine a small collection of very select objects at the tour's end. It is displayed two stories up in a small corner room, where groups are brought after their long tour downstairs. The relics do compete with a number of computer workstations in the large Multimedia Learning Center, also located on that floor, but by my observation, even TV-inured teenagers are so tired of screens by that point that they relish the opportunity to examine some tangible objects.6 These rare relics of the Holocaust, laid out simply in glass cases, include items of prisoner clothing, letters written by Anne Frank to pen pals in Iowa before the war, wooden bunk beds from the Maidanek death camp, music instruments crafted from the parchment of torah scrolls, and a ragged, hand-sewn American flag given by concentration camp inmates to their liberators. These genuine artifacts are very moving, and their emotional impact is heightened both by their scarcity and by the preceding long exposure to fast-paced, high-tech simulations. In contrast to most museums, where viewing large collections is physically exhausting, this gallery is eminently "manageable." Lingering as long as I wished and reading every text in the room, I still spent only 20 minutes in the small collection. Even as the Tolerance and Holocaust exhibits pale in visitors' minds, memories of these objects are apt to remain. Four years after a visit with a high-school youth leadership group, a college student recalled three things about the museum that had had the most impact on him. First and foremost were the original artifacts:7

If the benefits of the fast-paced media format outweigh its disadvantages, can the same be said about its appeal to emotion instead of intellect? Omer Bartov points out that the museum's reliance on media-driven emotional appeals to connect individuals with politics mirrors the strategy of mass manipulation employed by Hitler and his propaganda ministry.8 By privileging unreflective emotionality over rational understanding, Bartov suggests, the museum may even perpetuate one of the means employed make to Auschwitz possible. Some of the original exhibits were indeed condescending towards visitors. Omer Bartov wrote that they presume that the target audience is

My first reaction to the museum was similarly negative—I was embarrassed to have taken a whole day to expose my college honors students to such blatant and simplistic manipulation. However, some of the most embarrassing exhibits may have been beginners' mistakes—it is no mean feat to design an exhibit that exposes the hurtfulness of ethnic slurs, for instance. By now the most questionable exhibits have been replaced by more sophisticated stations. Additionally, the flashiness was not intended to appeal to bookish teachers who were already familiar with the history. To my surprise, even my college honors students learned quite a bit during their tour. They clearly came away with a more concrete notion of what the Holocaust was and why it happened. And, more importantly, they were motivated to learn more about various issues, some of which had been emphasized by the museum, and others which had not been presented. Should a museum, as Bartov suggests, promote "comprehension and contemplation, thought and analysis"? Certainly. But the more crucial question is: How can it promote them, especially among an audience of teenagers? David Altschüler, the director of the New York Holocaust museum, suggests one way:9

If we accept that museums may play only a brief, emotive role in the educational process, we should not expect them to achieve, in only a few hours, a historical understanding of the many events that were the Holocaust. University of Chicago historian Peter Novick, who studies Holocaust museums, said in an interview that "The notion of coming to any kind of historical understanding of what was going on there on the basis of spending a couple of hours looking at displays is nutsy."10 Is this a justification for the Los Angeles museum's blatantly manipulative approach? Might fewer gimmicks and more complex explanations make it even more effective? Perhaps for some people, but probably not for an audience of "90s kids with mall-sized appetites and Nintendo [attention] spans who were remote-zapping in the cradle," as one writer described the target audience.11 Does the Beit Hashoah—Museum of Tolerance help teachers guide their students towards a better understanding of the effects of hatred in our society? I think it does so quite effectively. Its exaggeratedly manipulative approach even offers more sophisticated visitors an opportunity to discuss or reflect about questions of representation and authenticity. That is something that a seemingly more objective museum such as the artifact-driven one in Washington is less apt to do.

Endnotes:

1. Judith Miller, One, by One, by One: Facing the Holocaust (New York: Touchstone, 1991), 248f. 2. Nicola Lisus and Richard V. Ericson, "Misplacing Memory: The Effects of Television Format on Holocaust Remembrance," British Journal of Sociology (1996). 3. Miller, One, by One, 243. 4. Apparently an even more realistic staging with crematorium smoke and human screams was once considered but rejected. See James Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven: Yale, 1993), 308. 5. Los Angeles Times, 3 Jan. 1993,A1 6. The computers offer access to an impressive 50,000 photographic images and 6000 texts. For a detailed discussion of the Multimedia Learning Center, see Michael Robin, "Remembrance and Learning: Multimedia Technology Adds a Participatory Dimension to the Simon Wiesenthal Center's Museum of Tolerance," Microtimes 128 (Oct. 17, 1994), 154ff. 7. B.G., "LA Museum of Tolerance," journal entry, 2 March 1998, photocopy in possession of this author. 8. Omer Bartov, Murder in our Midst (New York: Oxford, 1996), 183-86. 9. In Julie Salamon, "Walls That Echo of the Unspeakable," New York Times, 7 Sept. 1997, 84. 10. Geraldine Baum, "Do Holocaust Museums Make Us Better People?" Los Angeles Times, 11 Dec. 1997, E1,4. 11. Lisus and Ericson, "Misplacing Memory," 355 (after Hirshey). |