|

Stephen C. Feinstein Other Voices, v.2, n.1 (February 2000)

Copyright © 2000, Stephen C. Feinstein, all rights reserved The question of how to depict the Holocaust has been debated in many realms of representation—be it the theater, fictional writing, poetry, or especially the visual arts. The issue has become more complex in the postmodern era, as artistic sensitivity toward the subject has become enhanced and artists have begun to search for new means by which to approach discourse about the Shoah. Some contemporary artists have tried to sanctify the Holocaust as a subject, while others have developed a heavy reliance on either narrative or derivative images based on photographs. Inevitably, some of these representations may not have permanency as they seem to affirm what is known, rather than raise new questions. During the 1990s, some of the process of sanctification has given way to a form of deconstruction and innovation. This has appeared in many places simultaneously. In Germany, Horst Hoheisel, Stih and Schnock, and Esther and Joachim Gerz have developed anti-monuments for both their shock value and as a way to intellectually deal with the question of Jewish absence from Germany. Hoheisel proposed blowing up the Brandenberg Gate as a means of commemorating Jewish absence from Germany after the Shoah, and later produced a night projection on the Brandenberg Gate which read "Arbeit Macht Frei." The Gerz's built a disappearing monument in a Hamburg suburb, which has now been totally lowered into the ground. And Stih and Schnock have developed subversive street actions, provocations about the German past, in the form of reproduction public signs placed around Berlin to recall the persecution of the Jews. This provocative type of art has been found even in Israel. Roee Rosen constructed an installation for the Israel Museum in Jerusalem during 1997 entitled Live and Die as Eva Braun: Hitler's Mistress, in the Berlin Bunker and Beyond—An Illustrated Proposal for a Virtual-Reality Scenario, Not to be Realized. The exhibition featured an array of drawings accompanied by the crudely worded text allegedly written by Eva Braun. The show itself invited viewers to finish the work by using crayons. Needless to say, neither Holocaust survivors nor critics were amused by the display, and it was roundly criticized, with public demands to remove it from the Museum.1 This "shock" process has appeared in the works of several conceptual artists. One Polish artist, Zbigniew Libera, has gone well beyond the traditional representational boundaries to create edgy conceptual/pop-art about the Holocaust and contemporary genocide in general. His work has raised critical questions as to whether outlandish representations can help understand the Shoah, or whether just the opposite effect is created, an abusive and erroneous vision. Zbigniew Libera lives in Warsaw. During the late communist period in Poland, Libera served time in prison for drawing cartoons the regime judged "pornographic." However, the end of the Cold War and Poland's new freedom have provided him with the opportunities to travel, interact with the most avant-garde currents in modern art, and exhibit in the United States. Libera's focus is on commercialization and its impact on popular culture, as well as a vitriolic commentary on institutions with which he had to grow up. The result has been a well-defined pop art form, which perhaps establishes a limit in pop-art representation and at the same time provokes many questions of discourse about the Holocaust. Libera was born in Pabianicie, Poland in 1959 and studied in the Copernicus University in Torun. During the mid-1980s, he worked with the avant-garde group "Sternenhoch," and with the artists Andrezej Partum and Zofia Kulik. During the 1980s, Libera became known in Europe for his voyeuristic and controversial videos, including Intimate Rites (1984), How to Train Little Girls (1987) and Mystical Perseverance (1984-1990), which dealt with the topic of the hospital and death. In 1995, Libera moved fully into the area of pop art, constructing a series of works which mocked many of the obvious materialistic concerns of the democratic/capitalistic world and their icons, by then also appearing as consumer items in Poland. The first was Ken's Aunt (1995), produced in cooperation with Mattel Corporation complete with pink Barbie Doll boxes and clear plastic bubble wrapping. This "art object" was produced in an edition of 25 copies, and exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. Ken's Aunt is middle-aged, buxom version of Barbie, made up of "Cindy" dolls and complete with corset and a hairstyle more likely to be found in Poland than in the United States. Barbie, of course, has an entire history of her own, with origins in a German type of "sex doll" that became the first adult-version doll for American girls. The Polish title of Libera's work, Ciotka Kena, is a pun, as ciotka is a word for a relative as well as a derogatory reference to homosexuals.2 The doll is also, in a certain sense, a parody of contemporary ideals of beauty and cult of an ideal form of the female body, especially as the lean and always trim Barbie is sometimes referred to as a model for anorexia. From the perspective of the Holocaust, Libera's most provocative—and some might say most outrageous work—is Lego (1996), a seven-box limited edition of three LEGO sets of a concentration camp. Libera worked with the LEGO Corporation of Denmark to produce boxes which looked like "normal" LEGO systems. Inside were the bricks and other pieces to construct the concentration camp shown on the cover. The outer box looks like a normal LEGO box except in the upper left corner—instead of the "system number" is the inscription: "This work of Zbigniew Libera has been sponsored by LEGO."

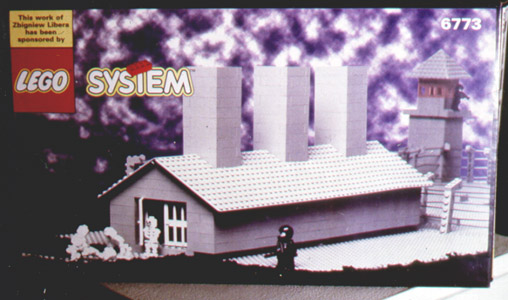

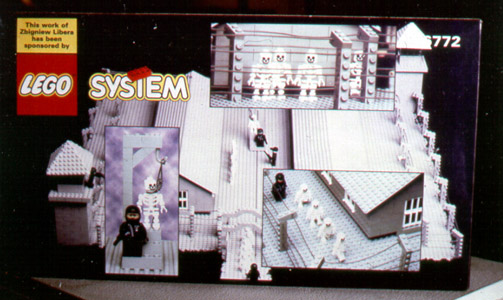

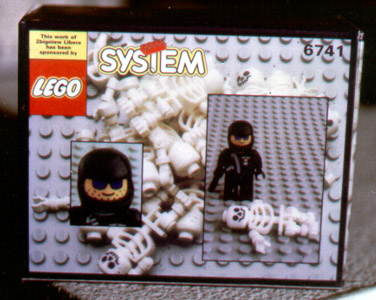

Zbigniew Libera (Warsaw), Correcting Device: Lego Concentration Camp. 1996. Original LEGO © plastic blocks and boxes made by the artist. Box 6773 Crematorium and Guard Tower. Reproduced with permission of the artist. The artistic product has not been endorsed by LEGO of Copenhagen, Denmark. Photograph by Stephen Feinstein. Each unit of the seven-box set contained a different aspect of a concentration camp. The larger boxes showed the entire concentration camp, with buildings, gallows (one showing an inmate being hanged), and inmates behind barbed wire or marching in line in and out of the camp. An entry gate similar to the stylized "Arbeit Macht Frei" entry point at Oswiecim is included, although without the German inscription. The guards, in black shiny uniforms, came from the regular LEGO police sets. The inmates came from LEGO medical or hospital sets. A second box showed a crematoria belching smoke from three chimneys, with sonnderkammando or other inmates carrying a corpse from the gassing room. The smaller boxes depict a guard bludgeoning an inmate, medical experiments, another hanging, and a commandant, reminiscent of something more from the Soviet Gulag than the Nazi concentration camp system, as he is bedecked with medals and wears a red hat. Some faces on both inmates and guards are slightly manipulated with paint, to make mouth expressions turn down into sadness for the inmates, and upwards in some form of glee for the guards. The last box is one full of possessions, the type of debris painted by other artists and inspired by the vast array of loots collected by the S.S. in the Kanada warehouses at Birkenau.

Zbigniew Libera (Warsaw), Correcting Device: Lego Concentration Camp. 1996. Original LEGO © plastic blocks and boxes made by the artist. Box 6773 Crematorium and Guard Tower. Reproduced with permission of the artist. The artistic product has not been endorsed by LEGO of Copenhagen, Denmark. Photograph by Stephen Feinstein. In a world where the normal obsession with violence is associated with guns, the mere idea of a "toy" concentration camp is enough to evoke strong responses, as was in the case at an international conference in December, 1997. When Libera showed this work to a group that included Jewish Holocaust survivors, he was immediately pelted with a barrage of insults which included "Go back to Warsaw!", "You're an anti-Semite," to "This is not art!"3 However, the issue debated at that particular conference was the question of how to keep discourse about the Holocaust "alive." Libera's Lego provided an answer, albeit not the one most were expecting. Many in the audience, even artists, were uncertain if this was an artwork with a limited edition (which it was) or a mass-produced item that was available in stores.

Zbigniew Libera (Warsaw), Correcting Device: Lego Concentration Camp. 1996. Original LEGO © plastic blocks and boxes made by the artist. Box 6773 Crematorium and Guard Tower. Reproduced with permission of the artist. The artistic product has not been endorsed by LEGO of Copenhagen, Denmark. Photograph by Stephen Feinstein. Then the issue of propriety of the subject, the sanctification of the victims was raised: was not the use of pop art as a means of depiction a mockery? Libera, when questioned about his work, said: "I am from Poland; I've been poisoned."4 During May 1997, Libera was invited to display his other pop art pieces in the Polish pavilion at the Venice Biennale, but was asked by Jan Stanislaw Wojciechowski, the curator, not to bring Lego.5 He wound up withdrawing from the exhibition. In fact, LEGO is a case of artistic representation which may have more answers about the Holocaust and contemporary genocide than most traditional art forms. First, the idea of a concentration camp available in toy and kit form was deemed offensive and not suitable for children. This discourse in itself raised the more important question of "from where did the Holocaust emerge?" Certainly, Hitler did not have a LEGO system, and the origins of his anti-Semitism and genocidal instinct is still being debated by historians. More importantly, Hitler was an aspiring art student rejected twice by the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, the last time being in October 1908. Beyond this, art held a very important place in the Nazi scheme of things. Libera's "lesson," if it may be said to be that, is that his Lego concentration camp was constructed entirely from existing LEGO stock, with a few minor exceptions which demanded adaptation.

Zbigniew Libera (Warsaw), Correcting Device: LEGO Concentration Camp. 1996. Original LEGO (c) plastic blocks and boxes made by the artist. Four small sets from the series. Reproduced with permission of the artist. The artistic product has not been endorsed by LEGO of Copenhagen, Denmark. Photograph by Stephen Feinstein. The LEGO Group from Copenhagen at first tried to stop Libera by bringing a lawsuit against him. However, the three sets of the LEGO Concentration Camp had already been sold, making a retraction even more difficult. On top of this, European copyright law, unlike that in the United States, permits use of corporate logos for artistic purposes. Thus, the lawsuit was soon dropped, although LEGO still goes through pains to ensure that museum viewers who now see Libera's work understand that it is not their product. Libera creates his pop art pieces in multiples, seemingly suggesting with Lego that history itself is repeatable. His Lego appears to be like many of the German concentration camps, which are almost in the artist's everyday field of vision as he lives in Poland. However, there is nothing specifically German about them, suggesting they could be in the Soviet Gulag, in Bosnia, or any location where genocide is being or has been carried out. The elements for such atrocity, as one reads Libera's pop-art, exists within civilization. All that is needed is the right person to "assemble" the pieces correctly. Commenting on this, Libera has noted that:

In fact, with Lego, the suggestion of a concentration camp is mainly on the box. Anyone assembling the material could make anything from it, depending upon imagination. Thus, the suggestion of the possibilities of constructing a concentration camp also suggests the antithesis—the construction of something else with the same materials. One may also take Lego as a starting point for analyzing aspects of violence in existing toys—from the obvious in guns to toy soldiers, "cowboys and Indians," and police toys. Libera is aware of this comparison. He noted that

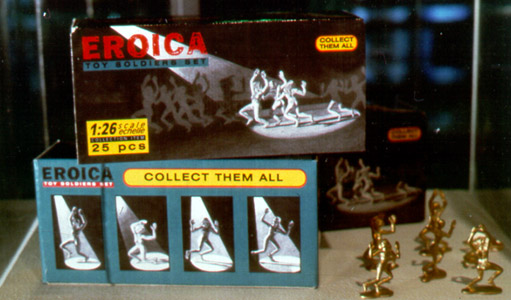

The idea of corporate logo, identifiability of product, and product reliability can easily be identified with some of the perpetrators of the Holocaust. The most advanced German corporations—I.G. Farben, Krupp, Siemens, Bayer A.G., BMW, Daimler-Benz, Volkswagen and others—profited from the Holocaust through their use of Jewish slave labor. Thus, product reliability in this context had nothing to do with moral or ethical positions, but everything to do with active participation in atrocity. Libera admits that he himself did not know exactly where he was going artistically when he applied to the Warsaw Representative of LEGO for permission to use the product name. His goal was "a rational architectonic construction which would be at the same time a complete, multiple and hierachiesed one...(a) kind of architecture which could be a factor of transformation of individuals: the architecture which influences those whom it shelters, which provides control, subordinates individuals to cognition and modifies them through discipline."8 Thus, to answer the complex question of where the Holocaust came from, Libera's answer, developed through creation of an outer edge in pop art, would be from the very essence of the society and the idea of "manipulation of human consciousness,"9 either through visible manipulation or something less compelling, such as the race for market-share domination by corporations. Thus, Libera has chosen to call all of his pop-art works "correcting devices," designed to create an awareness for children of the realities of the adult world. A second "correcting device" by Libera, Eroica, is a four-box set of toy soldier-sized female figures. They are based on classical models of slaves, or women seen in paintings such as Poussin's Rape of the Sabine Women. They are a reminder that in the 1990s, no toy soldier set is complete without the inclusion of women, who have become the special targets of victimization in genocidal settings such as Bosnia, where rape camps have been well-documented by The Hague War Crimes Tribunals, and most recently in Kosovo. Such is the fashion of "heroic" actions of armies in genocidal and even less violent encounters where woman are victims. The title of the work carries other cultural references as well. "Eroica" is the title of Ludwig von Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 in E flat. While the title perhaps suggests "erotic" or "eros," the title page of the printed score reads "Heroic Symphony composed to celebrate the memory of a great man," the reference being to Napoleon Bonaparte, who had defeated the Austrians at Austerlitz by the time the symphony was completed.10 The second and very slow movement of the "Eroica" is "Marcia Funebre" ("Funeral March"), appropriate also for Napoleonic Europe as well as the later twentieth century. Thus in this case, a seemingly simple and pop-art theme is actually an art work with many disguises, not at all about the Holocaust, but having a lot to do with genocide.

Zbigniew Libera (Warsaw), Correcting Device: Eroica. 1998. Four boxes of 25 Bronze nude female figures sized to scale with toy soldiers. Four variants of figures based on classical figures. Reproduced with permission of the artist. Photograph by Stephen Feinstein. Libera represents only one example of some of the boundaries that are being pushed by artists regarding a subject which has traditionally been sanctified. The desanctification may provide an edge to shake many viewers from complacency about the Shoah, and in fact provide simple and plausible answers to the question about its origins: all of the elements of a potential Holocaust or genocide surround us. All that is needed is someone to assemble them, and tell people how to use them. Most important is that the art does not sanctify and commit viewers to look only towards the past, but to engage in an active debate about ongoing genocidal events.

Endnotes:

1. Roee Rosen, Live and Die as Eva Braun: Hitler's Mistress, in the Berlin Bunker and Beyond-an Illustrated Proposal for a Virtual-Reality Scenario, Not to be Realized. (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1997). 2. Maret Bartelik, "Beyond Belief," Artforum, March, 1997. 3. Events at the Fondation Auschwitz conference Art After Auschwitz, Brussels, December, 1997, in which the author was a participant. 4. Libera speaking at Art After Auschwitz Conference, Fondation Auschwitz, Brussels, December 20, 1997. 5. Dean E. Murphy, "An Artist's Volatile Toy Story," Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1997. n.p. 6. Artist's statement by Zbigniew Libera dated Warsaw, December 19, 1996 (unpublished text). 7. Ibid. 8. Ibid. 9. Ibid. 10. "Sinfonia Eroica, composita per festeggiare la memmoria di un grand Uuomo," as indicated in notes for Ludwig von Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 in E flat. RCA Victor LP Album 1042, Commemorative Edition, Toscanini Tour, 1950. |