|

Bernd Herzogenrath Other Voices, v.1, n.3 (January 1999)

Copyright © 1999, Bernd Herzogenrath, all rights reserved

Introduction: On Mediation I want to begin this article on David Lynch's movie Lost Highway with a note concerning the use of Lacanian psychoanalysis in this paper. (1) Jonathan Culler has rightly argued that, "since literature takes as its subject all human experience, and particularly the ordering, interpreting, and articulating of experience, it is no accident that the most varied theoretical projects find instruction in literature and that their results are relevant to thinking about literature." (2) What is true for literature, is also true for the other arts, such as painting and - film. Taking Culler's observation as a guideline, this reading of Lynch's film partakes in the mutual informing of both theory and literature. Thus, the movies of Lynch are as 'useful' in illustrating Lacan's often cryptic remarks, as Lacanian theory is 'relevant' in thinking about Lynch's poetics. Lacanian psychoanalysis offers a theory of the subject that does without concepts such as unity, origin, continuity. It goes from the assumption of a fundamentally split subject and thus comes up with a model of subjectivity that grounds itself on a constitutive lack rather than wholeness. Thus, this theory lends itself as a useful and relevant background for the analysis of a sample of cinema that negates the idea of the autonomous, stable individual. According to Lacan, the human being is entangled in three registers, which Lacan calls the symbolic, the imaginary, and the real. Whereas the imaginary constitutes the (perceptual) realm of the ego, the register that accounts for a (however illusive) notion of wholeness and autonomy, the symbolic is the field of mediation that works according to a differential logic. Whereas the imaginary constantly tries to 'heal' the lack-of-being of the subject, the symbolic accepts castration. The human subject is thus doubly split: on the imaginary level between the ego and its mirror image, while on the symbolic level it is language and the inscription into a specific socio-cultural reality and its rules that bars the subject from any unity. Thus, this forever lost unity belongs to the third register: the real, which is simply that which eludes any representation, imaginary or symbolic. Because of this lack, the subject, which, according to Lacan, is an effect of the signifier, aims at recreating that lost unity. The 'strategy' of desire emerges as a result of the subject's separation from the real and the 'means' by which the subject tries to catch up with this real, lost unity again. It is thus desire that accounts for the subject's trajectory through the human world, which according to Lacan "isn't a world of things, it isn't a world of being, it is a world of desire as such." (3) This is true for Lynch's movies, as well for the relation of the spectator to the cinema in general. For a span of more than 20 years, director David Lynch has been forcibly changing the face of popular culture. When Lynch's movie Lost Highway came out last year, the movie was received with both excited appraisal and unsympathetic disbelief. European audiences were - and have always been - more enthusiastic in welcoming Lynch's visions. From Eraserhad onwards, through The Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart and Fire walk with me, Lynch's films have been immensely popular overseas, especially in France. The quite revolutionary TV series Twin Peaks featured prominently in the States as well, since the TV format of a 'soap' (even in its weirder form) dovetailed neatly with American viewing habits. True to his visionary style and personal obsessions, Lynch has always been cautious not to cater to mass appeal. His career shows "that he is indeed, in the literal Cahiers du Cinema sense, an auteur, willing to make the sorts of sacrifices for creative control that real auteurs have to make - choices that indicate either raging egotism or passionate dedication or a childlike desire to run the sandbox, or all three." (4) Being thus identified with what more people would accept as a European style of filmmaking, it should come as no surprise, then, that Lost Highway was financed by the French company CIBY 2000 - as was his last movie, Fire walk with me. Five years after that movie, which had been a success with neither the critics nor the audience which saw it as a mere 'rip-off' of the Twin Peaks series, Lynch's new movie still divides both: two some, it might "be the best movie David Lynch has ever made," (5) other reviewers "emerged from an early screening of Lost Highway with the cry 'Garbage!'" (6) So, what is the excitement all about? Although I am perfectly aware of the fact that any attempt to 'explain' Lost Highway ultimately results in a 'smoothening' of its complex structure into a linear narrative, I will try to give a short outline of its content. Ostensibly, Lost Highway is the story of Fred Madison, jazz musician. His wife, Renee, is a strangely withdrawn beauty. A disturbing study of contemporary marital hell, the first part of the movie concentrates on Fred's anxiety and insecurity, which escalates as he begins to realize that Renee may be leading a double life. Renee is the focus of Fred's paranoia: she is seen as both a precious object and the cause of her husband's nightmares. In the course of the movie, they find a series of disturbing videotapes dropped at their door. The first merely shows their house. The second depicts the couple in bed, from an incredibly strange angle. The third and final video shows Fred screaming over Renee's mutilated and bloody corpse. With brutal suddenness, Fred is convicted of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair, though he can't seem to remember anything. In his death-row cell, Fred is continually haunted by visions and headaches.

Such is the 'rough' plot. Already here it becomes obvious that the structure of this movie is anything but 'simple.' To this I am going to approach my subject asymptotically, that is, indirectly, in a series of excursions -- to circle my subject by way of digressions. DIGRESSION 1: ON SUTURE/SUTURE The enigmaticity of David Lynch's Lost Highway confronts us again with the question: What are we doing when we are watching a film? How do we read films? This very problem is and has been at the heart of Film Studies, in connection with a related question: does the diegetic reality of the film mimetically represent reality, or does it have the status of a symbolic, differential structure? As Peter Wollen has put it,

Both problems collide in the question if a movie as such is something that necessarily should be about something, or if the stance "against interpretation" is in fact the more appropriate attitude in particular towards postmodern cultural productions. David Lynch himself has warned against attempts at an unequivocal reading of a filmic text, especially when asked for the 'hidden meaning' of Lost Highway: "the beauty of a film that is more abstract is everybody has a different take. ... When you are spoon-fed a film, people instantly know what it is ... I love things that leave room to dream ..." (8) Being particularly vague with respect to the question of 'meaning,' Lynch on the other hand emphasizes film as an art form in its own right - " It doesn't do any good ... to say 'This is what it means.' Film is what it means" (Cinefantastique). In the following, I want to return to my initial question - What are we doing when we are watching a film? How do we read films? - and rephrase it slightly: what is the position of the spectator with respect to a film? Christian Metz, in his seminal study of cinema as The Imaginary Signifier (9), has tackled the problem from within a Lacanian framework. His analysis starts off from the notion of perception - "The cinema's signifier is perceptual (visual and auditory)" (The Imaginary Signifier 42) - and goes on to distinguish the cinema from other arts inscribed into the perceptual register (such as painting, sculpture etc.) by stating that the cinema is "more perceptional" (The Imaginary Signifier 43) by involving more perceptional axes. Compared with other types of the 'spectacle,' such as the theater or the opera, this apparent superiority, however, is thwarted by the fact that in the cinema, the spectator and the spectacle do not share the same space, since not only the diegetic reality of film is an illusion, "the unfolding itself is fictive: the actor, the 'décor,' the words one hears are all absent, everything is recorded" (The Imaginary Signifier 43). Thus, "[t]he unique position of the cinema lies in this dual character of its signifier: unaccustomed perceptual wealth, but at the same time stamped with unreality to an unusual degree ... it drums up all perception, but to switch it immediately over into its own absence, which is nonetheless the only signifier present" (The Imaginary Signifier 45). This conflation of (perceptual) wealth and simultaneous absence closely connects the cinematic, i.e. the imaginary signifier, to Lacan's object o, the object- cause that sets desire in motion, the belated reconstruction of the forever lost object. Metz himself draws this connection when he states with respect to film, that the lack is what it wishes to fill, and at the same time what it is always careful to leave gaping, in order to survive as desire. In the end it has no object, at any rate no real object; through real objects which are all substitutes (and all the more numerous and interchangeable for that), it pursues an imaginary object (a 'lost object') which is its true object, an object that has always been lost and is always desired as such. (The Imaginary Signifier 59) In further relating film to (and also

distinguishing it from) the dream, daydream and (conscious) fantasy

(and thus relating film to the status of a symptom, of a cultural -

or, culturally sanctioned - pathology), Metz' imaginary signifier

can be seen to be inscribed the Lacanian formula of desire, which is

also the formula of fantasy/the phantasma, and which reads According to Lacan, the subject is an effect of the signifier, of discourse, insofar that the signifier even "represents the subject for another signifier" (Écrits 316) The subject thus has to permanently re- invent and re-assure itself through its discourses - that is, through language, literature, and through film, among others. Miller defines suture as that moment where the subject fades by becoming represented - in discourse - by a signifier:

This definition not accidentally recalls Metz' observation that the spectator is as such missing from the cinematic discourse, and that the viewing subject might identify with the camera position as its stand-in. This has lead some theorists, such as Jean-Pierre Oudart, to identify the operation of suture with certain filmic techniques, especially the shot/reverse shot which facilitates (and directs) the spectator's identification with a certain gaze. Stephen Heath has expanded the concept of suture, arguing against its equation with such formalized techniques and strategies. Since the imaginary and the symbolic are always simultaneously present - an image having no value in itself, but always with reference to a cultural background, to a set of rules or genre-conventions - suture in Heath's account refers to the play of presence and absence as a mode of subject production in which the identification with the image always has to be read against the background of a symbolic system: "the spectator is always already in the symbolic ... No discourse without suture ... , but equally, no suture which is not from the beginning specifically defined within a particular system which gives it form ..." (13) With Lacan, the term suture denotes the "conjunction of the imaginary and the symbolic." (14) With respect to the Lacanian registers of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real, suture thus refers to the stitching of the representational registers, with the seam closing off the real from reality, closing off the unconscious from conscious discourse. Suture thus prevents the subject from losing its status as a subject, prevents it from falling into the void of the real, from falling into psychosis. Thus, the subject's identification with the movie fundamentally relies on this "conjunction of the imaginary and the symbolic" levels within the cinematic discourse itself. Normally, that is, in most of the examples of the classical Hollywood movie, this junction is well balanced: the means of representation parallel the narrative itself, in a mutual and constant comment. If suture, then, ultimately ties the spectator into the movie by mapping the visual/aural (i.e. perceptual, and thus imaginary) means of representation onto the narrative (and the structure of the narrative), the ripping open of that seam consequently has to result in a problematization, if not complete undermining of identification. This de-suturing then draws attention to the fabrication of the illusion of whole-ness of both the spectator and the movie. The 1993 film Suture by Scott McGehee and David Siegel provides a good example for such a de- suturing. (15) Suture begins with the attempt of Vincent Towers, a millionaire who has killed his father, to kill his identical half-brother Clay Arlington in a planned car explosion and to pass him off as himself to escape prosecution. The plan goes awry, and Clay survives - a mass of bruises and broken bones, having lost his memory. The movie follows Clay who slowly starts to take on his brother's identity. Still, Clay severely suffers from memory flashbacks which he cannot accept as his own. However, the end of the film - which indeed is its starting image as well, since the movie as such is a long flashback - shows Clay, who has by now fully accepted his new identity as Vincent Towers, shooting his brother who has returned to bring his plan to a successful close. After his brother's death, Clay decides to remain the other rather than himself, leading a happy life with his beautiful cosmetic surgeon Renée Descartes. No problem so far. But, on the level of representation, the spectator is constantly held in the process of de-suturing. The movie constantly emphasizes the physical similarity of the two brothers (on the blurb on the video jacket, they are actually referred to as 'twin brothers'), which is in fact a prerequisite for the film to function in the first place. "Our physical resemblance," remarks Vincent at one point, "is striking." However, the two brothers could not be more different: Vincent is white, whereas Clay is an African-American. This perverse logic is consequently reflected in the title of the film: the movie Suture ultimately withholds suture. (16) Lost Highway, I argue, functions in quite a similar manner. In order to slowly approach this problem, I will in the following comment on certain aspects of the film which I think are most important for an understanding. First, there is the structure of the film. After the credit titles that flicker over the screen - fittingly accompanied by David Bowie's song "I'm deranged," a track that sets the tone for what's to come - the movie begins with Fred sitting alone in front of a window, smoking, his image mirrored in the pane of glass, when suddenly a message comes in through the intercom: "Dick Laurent is dead!" (29K .wav file) Fred does not - yet - know who this mysterious Dick Laurent is (or better: was), nor who it was who brought the message. Neither does the spectator. Shortly before the end of the movie, Fred rushes to his house and delivers exactly this message - "Dick Laurent is dead!" - into his own intercom. Whereas most reviewers have failed to take notice of this strange structure, in favor of a more straightforward telling of the tale, even the one article that has mentioned it fails to acknowledge its real impact:

If we have a look - or much more importantly - a careful LISTEN - to these two scenes again ... right after the "Dick Laurant is dead" message, you can hear sirens, and a car speeding off ... in fact, they're the same sirens (and car speeding off) that occur at the end of the movie. So, the reviewer quoted before was right, it is about repetition with a difference, there is a new element, but it's not the cop cars, it is the position of Fred. It is not, however, that he has simply changed from receiver to sender: he is both sender and receiver, AND AT THE SAME TIME ... AND SPACE! In order to approach this mystery, a different topology is needed, a topology accounting for a time-space that differs markedly from Euclidean space and teleological time concepts. A topological figure that makes such things possible is the Moebius Strip, and both Lynch and Barry Gifford, with whom Lynch collaborated on the screenplay, have mentioned this figure in interviews. (18) So, what is a Moebius Strip? DIGRESSION 2: HOW TO MAKE A MOEBIUS STRIP

Ill 1: The Moebius Strip The Moebius Strip subverts the normal, i.e. Euclidean way of spatial (and, ultimately: temporal) representation, seemingly having two sides, but in fact having only one. At one point the two sides can be clearly distinguished, but when you traverse the strip as a whole, the two sides are experienced as being continuous. This figure is one of the topological figures studied and put to use by Lacan. (19) On the one hand, Lacan employs the Moebius Strip as a model to conceptualize the "return of the repressed," an issue important in Lost Highway as well. On the other hand, it can illustrate the way psychoanalysis conceptualizes certain binary oppositions, such as inside/outside, before/after, signifier/signified etc. - and can, with respect to Lost Highway, characterize Fred/Pete. These oppositions are normally seen as completely distinct; the Moebius Strip, however, enables us to see them as continuous with each other: the one, as it is, is the "truth" of the other, and vice versa. Reni Celeste invokes a similar topology, when she comments on Lynch's rewriting of American metaphysics, a rewriting that emphasizes the position where "violence meets tenderness, waking meets dream, blond meets brunette, lipstick meets blood, where something very sweet and innocuous becomes something very sick and degrading, at the very border where opposites becomes both discrete and indistinguishable" (Celeste). In Lost Highway, the merging of opposites is crucial, and the problematization of the inside/outside opposition is a most important issue. In fact, it is an important issue in Lynch's oeuvre as such - it suffices to refer to the scene in Blue Velvet, when the camera intrudes the severed ear that Jeffrey finds, and at the end of the movie, the camera virtually seems to come out of Jeffrey's ear again. In Lost Highway, the question of inside and outside and their conflation is repeatedly posed. On a general level, the diegetic reality of the movie - that what we actually see on the screen, as it were, INSIDE the movie - is composed out of bits and pieces from other movies: Lynch uses the different genres of Hollywood as a kind of quarry. And not only the Hollywood genres: he almost violently exploits his own wealth of images, almost every shot initiates the shock of recognition. One might call this repetitiveness, but, after all, language in general - and especially a distinct film-language such as Lynch's - relies on repetition in order to function.

Reni Celeste is correct when she observes that in Lost Highway, there are three important fissures: "that which exists between one discrete individual and another, that which exists between the individual and itself, and that which exists between the thing and its representation ... Th[e] Nameless Man [Celeste's name for the Mystery Man] ... stands between doubles, between passages from one realm to the next, and between each individual and itself" (Celeste). However, it is important to note that the structure of the Moebius Strip re-conceptualizes these fissures, allowing them to be seen not so much as fissures, or ruptures, but as places of transition. Lost Highway's moebial structure disallows the suture of the subject into the narrative. In contrast to the traditional Hollywood diegesis, in which the narrative unfolds in a straightforwardly telelogical manner - even in spite of displacing strategies such as flashbacks, or the "film within the film"-motif - Lost Highway in fact presents a multiple diegesis. The more so, since both stories - the story of Fred and the story of Pete - are not simply related to each other as prequel, and/or the solution of the other. Although there are definite anchoring points that clearly connect the two stories: the one does not subsume the other without remainder. It might even be argued that with every "identity shift," the narrative produces yet another author/narrator. Keeping to the Script I now want to refer to the attempts of categorization of the movie undertaken by its script writers. The movie has been dubbed by Lynch and Gifford (e.g., in the published version of the screenplay) as "A 21st Century Noir Horror Film. A graphic investigation into parallel identity crises. A world where time is dangerously out of control. A terrifying ride down the lost highway." Whereas the "time dangerously out of control" has already been hinted at in the section on the Moebius Strip, I want to use the remaining markers in the following as a kind of guideline. "A 21st Century Noir Horror Film. " "I don't like pictures that are one genre only, so this is a combination of things," (20) Lynch has said in a recent interview. Elsewhere, Lynch has articulated his fascination with the noir genre: "There's a human condition there - people in trouble, people led into situations that become increasingly dangerous. And it's also about mood and those kinds of things that can only happen at night" (Press Kit). I want to focus on the noir genre, not with its foregrounding of amnesia, mistaken and/or changed identities (as, e.g., in Dark Passage), of which there are obvious references in Lost Highway. I would like to concentrate on the genre's disturbed and disturbing urban environment, on the figures of mobsters and femme fatales, with respect to the Oedipal constellation that underlies the genre, and I think it is mainly in this connection that Lost Highway (and here especially the second part, Pete's story) can be regarded as a noir movie. (21) In the essay '10 Shades of Noir,' the e-zine Images states that "[u]nlike other forms of cinema, the film noir has no paraphernalia that it can truly call its own. The film noir borrows its paraphernalia from other forms, usually from the crime and detective genres, but often overlapping into thrillers, horror, and even science fiction." (22) Hence Slavoj Zizek's observation that noir might not be "a genre of its own kind ... [, but] a kind of logical operator introducing the same anamorphic distortion in every genre to which it is applied." (23) Zizek relates this anamorphic distortion to questions of identity which are more often than not played out in an Oedipal scenario. The first part of Lost Highway presents a marital scenario of uncertainty, anxiety, and unspoken suspicion. It takes place in a house which more resembles a fortress than a cosy home. From the film's beginning, we have the feeling of tension and fear: home, the family unit is the place of trouble and terror. This feeling is emphasized by Lynch's masterly employment of the soundtrack. For Lynch, "[h]alf of [a] film is picture ... the other half is sound. They've got to work together" (Press Kit). So, in Lynch's work, the soundtrack is a most important factor to enhance the mood of a scene. For example, during the dialogues between Fred and Renee there is no resonance to their voices. It is as if the works are spoken in a sound-absorbing environment, the whole spectrum of overtones, all those features that make a human voice seem alive, seems to have been cut. In its dryness, the voices of Renee and Fred almost seem to enact an absence of sound, or better - an absence of room, of the acoustics of space: it's as if they are living in a recording studio covered in acoustic tile. This soundscape underlines the similarity of this scenario with Lacan's subject being entangled in the register of the imaginary, most powerful symbolized in the child's symbiotic relationship with the Other, its mother. The incestuous two-ness is underlined by various devices. The strange lights in the Madison living-room, e.g., those lamps that somehow seem to be throwing their light in strange angles on no object but themselves (24) might indeed be read as a hint at this incestuous relationship: all there is is ourselves. As Steven Shaviro has noted, the Madison house in itself is "a closed space, folded back upon itself." (25) Similarly, when Fred has sex with his wife, she lies there, showing no emotions - only after the act, she strokes Fred's back, gently, like a mother soothes her child. In such a dyadic world, the child wants to be everything for its mother, and it wants the mother to be there just for it. (26)

Fred also feels that he is not everything to his wife. Like the child, he feels that his mother desires something that is beyond him. Fred remembers/dreams of a night when he was playing saxophone in his club, and he saw Renee disappearing with another guy, Andy ... one can see the neon EXIT sign there, and that's exactly how it is: Renee is looking for an exit/escape out of that prison-like symbiosis. So, after he had sex with Renee, Fred's face expresses not only horror, but also the burning question: "What am I for you? What am I for the Other?" So, somehow, Fred is precisely dependent on the desire of the Other, and therefore it is necessary for him that the Other, Renee, exactly remains in her position as love-giving, complete Mother, unspoiled by any lack - and it is such a lack that the mother reveals in her desire for someone else, and also the lack in the child, Fred, since he is seen as incapable of filling the lack. Thus, the imaginary scenario is an attempt of Fred's to disavow castration by all means. In the second part of the movie, Fred's story,

the Oedipal scenario is brought to the fore even stronger. Here,

now, we have Fred, the young man; Alice, the femme fatale;

and Mr. Eddy, the father-like mobster. Father, because both of his

age, and because he treats Pete with a kind of paternal attitude. In

Lacanian terminology, the father-figure is accepted by the subject

as its ideal-ego, and as such serves for the internalization of the

laws of society. However, the flip-side of this benevolent figure of

the ideal-ego is the super-ego, the father as "perverse

father," the exception at the origin of the law. The Master,

the Father, he who gives the Law is an "obscene, ferocious

figure" (Écrits 256) that "imposes a

senseless, destructive ... almost always anti-legal morality."

(28) To imagine what is at stake,

it suffices to recall Freud's notion of the Urhorde.

"A graphic investigation into parallel identity crises" It is the phrase parallel identity crises that interests me the most here. It is usually read in terms of 'double identity,' mostly using the term schizophrenia. There has been quite some misunderstanding about this very term. In 1911, the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler replaced Kraepelin's term for a group of psychoses, dementia praecox, with the term schizophrenia. Dementia praecox meant a psychosis of early onset, which Bleuler wanted to capture with the term schizophrenia, meaning literally "split mind," since he thought the splitting of psychic functions to be the structuring element of these psychoses. Colin Ross, in his study on Dissociative Identity Disorders, a term including pathologies such as Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) and the Borderline Syndrome, states that, "dementia praecox is actually a better name for this group of disorders [described by Kraeplin] than schizophrenia, while schizophrenia is a better name for [Dissociative Identity Disorder] than multiple persona disorder." (31) Hence the popular notion of schizophrenia as "split personality," a misconception that does not account for the fact that schizophrenia is an organic disorder of the brain, and not actually a personality disorder. In addition to this reading of "parallel identity crises" in terms of "split personality," I want to suggest some further thoughts that account for this split with reference to the structure of the Moebius Strip. Thus, it is not that simple that Pete's story is only the reverse of Fred's story (remember, a Moebius Strip has no such thing as a reverse side - it is one-sided!). Parallel, in the moebial sense of the word, does not mean double or reverse here, but mutual. Pete's story is not only the reverse side of Fred's story, simultaneously Fred's story has to be the reverse side of Pete's story ... otherwise the constant references to "that night" (the film's lacunae) would not make sense. True to the logic of the Moebius Strip, what on a very local level seem to be two sides of the story is actually one. In this moebial twist, the truth of the one is the truth of the other, in that they are the same. On the level of the images of the movie, this complicity can be shown by a comparison of two scenes that occur more than once in Lost Highway. These two scenes of Fred in the dark hallway (Renee calling "Fred!") and Pete in front of his parents' house (Sheila calling "Pete!"), viewed in parallel, function like a kind of worm-hole which traverses the different event-levels of the movie - I would even argue that if you mirrored those two scenes onto two screens put next to each other, it would have the effect of the one character changing over to the realm/screen of the other. Another 'perspective' of this simultaneous immersion can be seen in the "transformation scene." Here again, the moebial twist of inside and outside, one and other, is brought to the fore, this time effected by shots intruding the inside of the body. "[Psychogenic] Fugue" A last reference I want to make use of is the term "psychogenic fugue" that the French Production Company of Lost Highway, CIBY 2000, used as a kind of short- hand plot-synopsis in their pre-publicity campaign for the movie. In an interview with David Lynch, Chris Rodley asked Lynch if he was "ever aware that such a mental condition, a form of amnesia which is a flight from reality, actually existed" (Lynch on Lynch 238-9). Lynch answered that

Yet it does mean something, and in this last section of this article, I want to situate Lost Highway in the context of human pathology. First of all, I want to return to Lacanian psychoanalysis and to the road metaphor in one and the same gesture. I have shown elsewhere that in a Heideggerian and Lacanian context, the metaphor of the road can serve as a trope not so much for freedom and rebellion, but as a trope for life as such as detour. (32) Lacan employs the metaphor of the road in his account of the death drive, (33) but he makes it unmistakably clear that such a notion of the drive is far from representing an imaginary and narcissistic freedom from any law whatsoever. Even this drive for freedom depends for its existence on laws, on barriers ... freedom needs barriers for their transgression. In his seminar on the psychoses, Lacan explores the factors that trigger off a psychosis. And again, he takes recourse to the metaphor of the road. In a chapter appropriately named "The highway and the signifier 'being a father,'" he writes:

What Lacan is alluding here to is his notion of the point de capiton, the quilting point, which is that point which makes sure that some temporary notion of meaning can be created in language. Again, as in the concept of suture, the metaphor of stitching and sewing comes to the fore, since a quilting point designates an upholstery button, a place where "the mattress-makers needle has worked hard to prevent a shapeless mass of stuffing from moving to freely about." (35) So a point de capiton is a place where signified and signifier are literally stitched together - this is suture in the register of the symbolic. Like a highway with respect to a system of smaller streets, the quilting point holds that system of discourse together, and a minimal number of these points are "necessary for a human being to be called normal, and which, when they are not established, or when they give way, make a psychotic" (Seminar III 268-9). According to Lacan, the most important points de capiton, the highway amongst some minor roads, so to speak, is the name of the father, the paternal metaphor, which is quite important in Lynch's "post-patriarchal project." (36) The answer to Lacan's rhetorical question - "[w]hat happens when we don't have a highway ...?" (Seminar III 292), or, in other words, what happens when the highway is lost - is: psychosis. The foreclosure, what Freud called Verwerfung, of the primordial signifier, the name of the father, is a strategy for evading castration: the subject is "castrated" by its entry into the symbolic, into language and society. Thus, the denial of this castration leads to psychosis. This rejection of the symbolic Other that results in the disappearance of the phallic function leads to the subject's distortion of its relation to the social order as well to its loss of sexual identity. As in Freud's case of Judge Schreber, Fred Madison tries to escape the threat of castration, but he experiences a "return of the repressed" in the real instead of in the symbolic, in his hallucinations (that is, in his second identity as Pete), because he does not accept the name of the father, the agency that might disturb his symbiotic relationship with Renee and/or Alice: Dick Laurent is dead! So, the "Highway" of the title is exactly this quilting point, this suture, that would be necessary for the subject to be inscribed into "reality," into a state of "normality." Once this point is lost, once this seam is undone, the subject falls prey to the real, becomes psychotic. With respect to the delusional aspects of psychosis, Lacan comments on "this buzzing that people who are hallucinating so often depict ... this continuous murmur ... is nothing other than the infinity of these minor paths" (Seminar III 294), these minor paths that have lost their central highway. What is the deep droning sound underlying most of the movie but this "continuous murmur?" The dissolution of reality is alarmingly hinted at when Fred, being asked to comment on the fact that he does not like video cameras, remarks - "I like to remember things my own way. ... How I remember them, not necessarily the way they happened." (117K .wav file) (37) Seen in this light, the videos might represent the truth "the way it happened," that is: the repressed truth of Fred (and it is here that the sequence of the burning cabin shot in reverse gains special significance as a recurring image of that repression). Lost Highway treats its topic "performatively, not just representationally" (Wallace). Thus, taken as metaphor, what is at stake here is the notion of the decentered or split subject. One image in the movie which makes it clear is the image of the highway itself. There are two variants of this specific shot that are important here. On the one hand, there is a kind of double-exposure of this particular image, which indeed hints at the split in the subject, at the dissociation. (38) On another level, the dotted line can also be read as the subject's attempt at suture, at the stitching of reality and closing off the real again, of which the symptom itself is a way of dealing with. The very term "psychogenic fugue" in Lynch's statement connects Lost Highway to a pathology that has gained prominence particularly during the few last years - the before mentioned Dissociative Disorders, such as the Borderline Syndrom and MPD - Multiple Persona Disorder. The term "psychogenic fugue" in particular is closely connected to the latter. The symptom called "psychogenic fugue"

It is widely acknowledged that this symptom, closely connected to a kind of "time-loss" in the patient's memory, is a common feature of MPD, a disorder having entered mass consciousness through the biography, case study and movie The 3 Faces of Eve, starring Joanne Woodward. (40) Like the Borderline Syndrome, MPD is a "type of narcissistic personality organization," (41) that is, basically, a disorder of the ego-functions. Whereas in the Borderline Syndrome, the subject is unable to create a coherent ego, that is, to create the illusion of autonomy, MPD refers to the splitting of the subject's ego into several compartmentalized personae. The revised third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-III-R] gives the following criteria for MPD:

The main reason for the onset of MPD is to be found in traumatic experiences, one of the most common of which is continuous sexual abuse, mostly in early childhood. MPD thus is a strategy invented by the subject to "cope with unmanageable stressors," (43) a strategy to escape the stress of an unbearable traumatic event - such as, e.g., the murder of one's own wife. [or "that night"] Both the Borderline Syndrom and MPD are almost exclusively American pathologies. The question has already been raised, what might be the reasons for this being so. Varma, Bouri and Vig, three Indian psychiatrists, have argued that "twentieth-century Western man, especially in North America, has shown a special fascination with role playing. The role is adopted with some gain or favourable outcome in mind. The fulfillment of the role may make him act even in a manner contrary to his usual self ... The role adopted, like in multiple personality ... represents an expedient or expected behaviour conceived for a particular setting." (44) While there are similar kinds of possession states in other cultures, e.g. Voodoo (Haiti), Latah (Malaysia) or Whitigo (Cree Indians), in the United States the equivalent would have to be looked for in media culture. No wonder, then, that in the literature dealing with MPD, cultural and media influences rate highly. Ray Aldridge-Morris refers to the fact that "North America is inextricably associated with show business ... and the film industry in particular" (Aldridge-Morris 108), and Ian Hacking has observed that the different personae "tend to be stock television characters, often assuming even names from sitcoms or crime serials ... Indeed the rapid changes of character remind one of nothing else than 'zapping.'" (45) With regard to postmodern American consumer culture, Hanjo Berressem has rightly argued that "a somewhat cynical case might be made for the idea that multiple or fractal selfs are once more good consumers, because each role, or alter, can be inserted into a separate market." (46) With respect to Lost Highway, it has to be noted that the narrative of the movie is located in Los Angeles, the film metropole. Another point which I think might be worth-wile analyzing is the function of the abundance of references to means of media and communication in this movie: videotapes, camcorders, cell phones, phones, the intercom. The whole movie, as it seems, is penetrated by a kind of communicational electro-smog, and somehow all of these devices are related to very strange and mysterious powers. Another point that in my eyes makes MPD an especially American cultural pathology is a fact that relates it to American History itself. Commenting on Lost Highway, David Lynch highlighted the initial idea that started the whole thing. "What if one person woke up one day and was another person?" (Cinefantastique). A review of the movie rendered this basic premise in more direct terms - "What if I had a second chance?" (Review by Steve Biodrowski in Cinefantastique). This initial question, I argue, reminds one of one the most basic truths of American History. John T. Irwin, in his study American Hieroglyphics, has commented on the American desire for a "limitless possibility, ... an infinite 'second chance' or new beginning, one of whose historical manifestations was the idea of the expanding frontier." (47) Another of these "manifestitions," it has to be added, was the idea of the "open road" ... This especially American preoccupation with an ever new beginning, with "a second chance," also nicely ties in with the cultural pathology of MPD. The clinical picture of MPD, I argue, is put to use in Lost Highway as a metaphor for the split, decentered subject, in a similar way of Allucquere Rosanna Stone's and Sherry Turkle's treatment of this parallel. Turkle writes:

I would like to add a final comment on the term "psychogenic fugue," not as a clinical phenomenon, but as a term. In his interview with Lynch, Chris Rodley also mentioned the connection with the musical term fugue, describing it as "one theme starts and is then taken up by a second theme in answer. But the first continues to supply an accompaniment or counter-theme ... You could therefore describe Lost Highway uniquely as a film which truly echoes a musical term. ... Did you and Angelo Badalamenti discuss the score in terms of a fugue?" (Lynch on Lynch 239). After giving you the additional information that in a fugue, not only one theme is taken up by a second theme, but also by another instrument, another voice, I want to give you Lynch's answer, which I think is quite revealing. He said, "Fugues make me feel insane. I can only listen to a certain amount of a fugue, and then I feel like I'm gonna blow up from the inside out" (Lynch on Lynch 239). (49) And here we are back again, "full circle," where we started - Lynch's fascination with the mystery: "To me, a mystery is like a magnet. Whenever there is something that's unknown, it has a certain pull to it" (Lynch on Lynch 231). Lacan, in his evaluation of the mystery, of that which cannot by symbolized, but which nevertheless has immense effects in symbolization, goes even further: "The tip of meaning, one can sense it, is the enigma," (50) insofar as meaning as such is something that can never be halted, never be fixed - there is always a remainder. This remainder, I argue, that which cannot be symbolized, is on the one hand given in the movie as a kind of excess of the images, a kind of surplus-value of the imaginary which manifests itself in moments of jouissance. On the other hand, the enigma in Lost Highway takes on its most concrete form in the gaps and voids, in the long sequences of darkness that permeate the whole movie. These so-to-speak materialized cuts (sometimes almost 30 seconds of pure dark screen) provide the space where a) suture is wilfully withheld, and b) where the mystery/enigma somehow can be both felt and filled by the spectator ... finally, there is - or: can be - a certain strange version of suture that functions by alining the gaps in the cinematic discourse with the desire of the spectator: in filling the gaps with his own interpretations/obsessions/images, he becomes an important part of the diegetic reality of the movie, a kind of lynchian version of unconscious interactivity. So, what happens to Fred in the end? The very last shot shows him in the process of transformation again. Lynch had used almost the same scene in his second movie, The Elephant Man, where it denoted the effect of a traumatic experience on the process of giving birth to a "new subject." What will be the result of Fred's transformation? Yet another persona? Or, will he re-transform into Pete, thus adding another temporal twist to the narrative - remember that Pete had been imprisoned once, not for murder, but for car-theft, and what the police will eventually find after Fred has transformed into Pete again, will simply be Pete, in a stolen car ... only that now, since the cops had found Pete's fingerprints all over Andy's place, Pete will be charged for murder ... but, does that explain things? Do we now understand? In the recent remake of the thriller Nightwatch, now called Freeze, the police inspector turned serial-killer, played by Nick Nolte, philosophizes: "Explanations are just fictions to make us feel safe. Otherwise, we would have to admit the unexplained, and that would leave us prey to the chaos around us. Which is exactly what it is." Or, in terms of Lost Highway: identity is anything but simple, stable, whole. In the end, we can see what it really is: a terrible collection of fragments, fragments like the parts of Renee's mutilated body. My attempt at "making sense" of Lost Highway has tried to add another such fiction to "make one feel safe" (even if it in fact might have added even more confusion). (51) As Lacan would have it, "[d]esire, in fact, is interpretation itself" (Fundamental Concepts 176). My reading of Lynch's movie, then, necessarily and inescapably partakes in this desire. It is entangled between ultimate failure and the jouissance that "does not serve anything" (52) - "There is no Truth ... But one runs after it all the same" (Fundamental Concepts vii).

Endnotes:

1 This

paper is a slightly revised version of a talk I gave at the American

Studies Colloquium 1998 in Olomouc, Czech Republic.

2 Jonathan

Culler. On Deconstruction. Theory and Criticism after

Structuralism. Ithaka, New York, 1982, 10.

3 Jacques

Lacan. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book II: The Ego in Freud's

Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-55. Trans. S.

Tomaselli. Cambridge, 1988, 222. Subsequently quoted as (Seminar

II).

4 David

Foster Wallace. Article on Lost Highway in Premiere,

Sept. 1996. http://www.m

ikedunn.com/lynch/lh/lhpremiere.html Subsequently quoted as

(Wallace).

5 Mikal

Gilmore. Article on Lost Highway and Interview with David

Lynch. Rolling Stone, March 6, 1997. http://www.mikedu

nn.com/lynch/lh/lhrs1.html

6 Richard

Corliss. 'Mild at Heart.' TIME, April 7, 1997, 77.

7 Peter

Wollen. Readings and Writings: Semiotic Counter-Strategies.

London, 1982, 2.

8 Frederick

Szebin and Steve Biodrowski. 'A surreal meditation on love,

jealousy, identity and reality.' Cinefantastique, April 1997.

http://www.miked

unn.com/lynch/lh/cinelh.html Subsequently quoted as

(Cinefantastique).

9 Christian

Metz. The Imaginary Signifier. Psychoanalysis and the Cinema.

Trans. C. Britton, A. Williams, B. Brewster and A Guzzetti.

Bloomington, 1982. Subsequently quoted as (The Imaginary

Signifier).

10 Jacques Lacan. Écrits. French

Edition. Paris, 1966, 774. Subsequently quoted as (Écrits),

referring to the English translation Écrits. A

Selection, by A. Sheridan, New York 1977.

11 Cp.

Kaja Silverman's account of this concept in her study The Subject of

Semiotics. New York, 1983, 194-236, subsequently quoted as

(Subject of Semiotics).

12 Jacques-Alain Miller. 'Suture (elements

of the logic of the signifier).' Screen 18:4, (1977/78), 24-

34, 25-6.

13 Cp.

Stephen Heath. Questions of Cinema. Bloomington, 1981, 'On

Suture,' 76-112, 100-1. Cp. also the chapter entitled 'On Screen, in

Frame: Film and Ideology' (1-18).

14 Jacques Lacan. The Four Fundamental

Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Trans. A. Sheridan. New York,

London, 1978, 118. Subsequently quoted as (Fundamental

Concepts).

15 For

another comparative reading of the concept of suture and the movie

Suture, cp. Hanjo Berressem. Twisted and Traumatized:

Spatial and Temporal Loops in American Literature, Art, and

Culture. Habilitationsschrift, Aachen 1997.

16 Another short reference to yet another

movie: John Woo's Face/Off. In this movie, two men exchange

identities; that is, they change faces. Suture,

Face/Off, and Lost Highway - they all tackle the

question of identity and of suture ... in a way, all three movies

are "about" identity and its vicissitudes, about the construction of

both the subject in the diegetic reality of the movie, and of the

spectator. Suture thematizes the concept of identity as an

effect of (illusory) identification, and ultimately withholds the

comfort of suture, of a stable position both within diegetic reality

and off-screen. John Woo's Face/Off comments on the

Aristotelean truth that physiognomy mirrors character. This truth is

countered with an almost metaphysical sense of self beyond mere

looks, a self, however, that most prominently reveals itself in a

language of the body, in small gestures. The suture that

holds the movie together is quite literally the seam which stitches

Nicholas Cage's face onto John Travolta's head (and vice versa) and

'functions' in fact only if the spectator is willing to accept this

improbability. In Lost Highway finally, the identity of the

on-screen subject is related to different positions it takes with

respect to different levels of "reality," and, ultimately, to its

desire. Since this is a never-ending process, suture, for the

spectator, is forever displaced and deferred.

17 Reni

Celeste. 'Lost Highway: Unveiling Cinema's Yellow Brick Road.'

Cineaction 43 (Summer 1997). http://www.mailbase.ac.uk/lists

/film-philosophy/files/paper.celeste.html. Subsequently quoted

as (Celeste).

18 see

e.g. Lynch in the Official Press Kit for Lost Highway, http://www.mike

dunn.com/lynch/lh/lhpress.html, subsequently quoted as (Press

Kit), and Gifford in his interview for Film Threat, http://www.mi

kedunn.com/lynch/lh/lhgifford.html.

19 Cp.

e.g. Lacan's discussion of the figure of the "interior eight" in his

article on 'Science et Verité' (Écrits, French edition, 855-77), or

his 1966 lecture 'Of Structure as an Inmixing of an Otherness

Prerequisite to Any Subject Whatever,' published in: The

Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the

Sciences of Man. Ed. R. Macksey and E. Donato. Baltimore, 1970,

186-200. The illustration was taken from this article.

20 Chris

Rodley (ed.). Lynch on Lynch. London, Boston, 1997, 231.

Subsequently quoted as (Lynch on Lynch).

21 On yet

another level, Lost Highway is obviously a noir film

in a very literal sense: noir/black is the prevailing color

in this movie, especially in the long dark sequences that seem to

structure the narrative ...

22 '10

Shades of Noir. Film Noir: An Introduction.' Image e-zine,

http://www.imagesjournal.com/issue02/infocus/filmnoir.htm.

23 Slavoj

ZiZek. Tarrying with the Negative. Durham 1993, 9-10.

24 Georg

Seeßlen has made similar observation, but has related this

observation in his conclusions to the concept of self-reflexivity in

Lynch's filmic language. See Georg Seeßlen. David Lynch und

seine Filme. Marburg und Berlin, 3. erw. Auflage 1997, 187.

25 Steven

Shaviro. Stranded in the Jungle. (forthcoming book; excerpts

can already be found on Steven Shaviro's homepage; see his chapter

'Intrusion' on Lost Highway:

http://www.dhalgren.com/Stranded/18.html

26 Or,

when Fred asks Renee if she will come to the club, she answers that

she wants to read, and Fred asks, in disbelief, "Read? Read what?"

Apart from this articulation of an otherwise unspoken suspicion that

Renee might actually be an unfaithful wife, this remark of Fred's

also shows his inability (or: unwillingness) to accept the need for

something that goes beyond this symbiosis ... maybe, one has

to read "Read" very literally as a hint towards the symbolic, the

agency that in the end very violently disturbs this dual

relationship.

27 Michael Chion has already noted in his

seminal study Audio-Vision. Sound on Screen. Trans. Claudia

Gorbman. New York, 1994, that Lynch is one of the directors that

have liberated film sound from its long sleep of simply accompanying

the images on-screen. Chion points out that Lynch is one of those

who have developed the soundtrack into the direction of a "Sound

Film - Worthy of the Name" (141).

28 Jacques Lacan. The Seminar of Jacques

Lacan Book I: Freud's Paper on Technique 1953-54. Transl. by J.

Forrester. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, 102.

29 see

Slavoj Zizek. The Plague of Fantasies. New York, London, 1997.

30 see

Slavoj Zizek's interpretation of Hitchcock's Psycho with

respect to this moebial twist in Slavoj Zizek (ed.). Everything

you always wanted to know about Lacan (but were afraid to ask

Hitchcock). New York, London, 1992.

31 Colin

Ross. Dissociative Identity Disorder. Diagnosis, Clinical

Features, and Treatment of Multiple Personality. New York, 1997.

32 See

Chapter 7, 'On the road: The Road Novel and the Road Movie,'

of my book An Art of Desire. Reading Paul Auster. Amsterdam

and Atlanta, 1999, 159-72.

33 Cp.

Jacques Lacan. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book II: The Ego in

Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-55.

Trans. S. Tomaselli. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988,

where he comments on the "roads of life" (81) and describes life as

a "dogged detour" (232) towards death.

34 Jacques Lacan. The Seminar of

Jacques Lacan. Book III: The Psychoses, 1955-56. Transl. by R.

Grigg. New York, 1993, 290-1. Subsequently quoted as (Seminar

III). An example might clarify what is at stake here. Kafka, in

his Letter to the Father, takes recourse to another

topographical metaphor, referring to his father in terms of a

dimension spread out in space: "Sometimes I imagine the map

of the world spread out and you stretched diagonally across it."

Franz Kafka. Letter to the Father. Prague, 1998, 65.

35 Malcolm Bowie. Lacan. London,

1991, 74.

36 This

term is Anne Jerslev's. See her study David Lynch i vore

řjne. Copenhagen, 1991.

37 Thus,

the whole second part of the movie (Pete's story), can be read as

Fred's attempt to "remember things" his own way, even to re-member,

in the literal sense of the word, both his fragmented sense of self

and Renee's dis-membered body ...

38 A more

hypermaterialistic rendition of the split subject is the

scene in which Andy's head is virtually split by the glass table ...

it's as "literal" as you can get.

39 Frank

W. Putnam. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Persona

Disorder. New York, 1989. 13-4. Subsequently quoted as (Putnam).

40 The

case of Eve has just recently been found out to have been faked by

the analysts.

41 Clary,

W.F., Burstin, K.J., & Carpenter, J.S. 'Multiple personality and

borderline personality disorder.' Psychiatric Clinics of North

America, 7 (1984), 89-100.

42 American Psychiatric Association.

DSM-III-R. Washington, 1987, 106.

43 Ray

Aldridge-Morris. Multiple Personality. An Exercise in

Deception. Hove, 1989, 107. Subsequently quoted as (Aldridge-

Morris).

44 Varma,

V.K., Bouri, M., & Wig, N.N. 'Multiple personality in India:

Comparison with hysterical possession states.' American Journal

of Psychotherapy 35 (1981), 1.

45 Ian

Hacking. 'Multiple Personality Disorder and Its Hosts.' History

of the Human Sciences 5.2 (1992), 3-31, 11.

46 Hanjo

Berressem. 'Emotions Flattened and Scattered: "Borderline Syndromes"

and "Multiple Persona Disorders" in Contemporary American Fiction.'

in: G. Hoffmann, A. Hornung (ed.). Emotion in Postmodernism.

Heidelberg, 1997, 271-307, 293.

47 John

T. Irwin. American Hieroglyphics. The Symbol of the

Egyptian Hieroglyphics in the American Renaissance. New Haven

and London, 1980, 112.

48 Sherry

Turkle. Constructions and Reconstructions of the Self in Virtual

Reality. Quoted in Allucquere Rosanne Stone. 'Identity in

Oshkosh.' J. Halberstam, I. Livingston (ed.). Posthuman

Bodies. Bloomington, 1995, 23-37, 34.

49 Another, I think, most revealing

information with respect to the fugue: Douglas R. Hofstadter, in his

book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, comments

on the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach, which, in his time,

were judged as quite notorious. Like Lynch's works, they were either

thought to be pompous and confused, whereas others hailed them as

masterpieces. For Hofstadter, Bach's fugues in general, and

especially his highly complex fugue Ein Musikalisches Opfer/A

Musical Offering, are of special importance for his study

because of their structure, which is the structure of what

Hofstadter calls "strange loops." A most prominent example of such a

strange loop is ... yes, it's the Moebius Strip again. And, finally,

believe it or not, the original term for the fugue was the Latin

term Ricercar, which means - enigma, mystery. Cp. Douglas R.

Hofstadter. Gödel, Escher Bach. An Eternal Golden Braid. New

York, 1979.

50 Jacques Lacan. 'Vorwort zur dt. Ausgabe

meiner Schriften.' in: Schriften II. Weinheim, 1991, 7.

51 Only

after I finished this article (and the talk on which this article is

based), Troels Degn Johansson, Department of Film & Media Studies of

the University of Copenhagen, pointed out an article to me in

cinetext by Robert Blanchet: 'Circulus Vitiosus:

Spurensuche auf David Lynchs Lost Highway mit Slavoj ?i?ek.'

This article only mentions in passim some of the aspects I

have tried to discuss in more detail in this paper, so, both

articles somehow respond to each other like the "two sides" of a

Moebius Strip as well ... cp. http://st1hobel.phl.univie.ac.at/cinetext/magazine/circvit.html

52 Le

Séminaire Livre XX: Encore. Paris, 1975, 10. My translation.

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-III-

R. Washington, 1987.

Ray Aldridge-Morris. Multiple Personality. An

Exercise in Deception. Hove, 1989.

Hanjo Berressem. Twisted and Traumatized:

Spatial and Temporal Loops in American Literature, Art, and

Culture. Habilitationsschrift, Aachen 1997.

---- . 'Emotions Flattened and Scattered:

"Borderline Syndromes" and "Multiple Persona Disorders" in

Contemporary American Fiction.' in: G. Hoffmann, A. Hornung (ed.).

Emotion in Postmodernism. Heidelberg, 1997, 271-307.

Robert Blanchet: 'Circulus Vitiosus:

Spurensuche auf David Lynchs Lost Highway mit Slavoj

Zizek.' http://st1hobel.phl.univie.ac.at/cinetext/magazine/circvit.html

Malcolm Bowie. Lacan. London, 1991.

Reni Celeste. 'Lost Highway: Unveiling Cinema's

Yellow Brick Road.' Cineaction 43 (Summer 1997).

http://www.mailbase.ac.uk/lists

/film-philosophy/files/paper.celeste.html.

Michael Chion. Audio-Vision. Sound on

Screen. Trans. Claudia Gorbman. New York, 1994.

Clary, W.F., Burstin, K.J., & Carpenter, J.S.

'Multiple personality and borderline personality disorder.'

Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 7 (1984), 89-100.

Richard Corliss. 'Mild at Heart.' TIME,

April 7, 1997, 77.

Mikal Gilmore. Article on Lost Highway and

Interview with David Lynch. Rolling Stone, March 6, 1997.

http://www.mikedu

nn.com/lynch/lh/lhrs1.html

Ian Hacking. 'Multiple Personality Disorder and

Its Hosts.' History of the Human Sciences 5.2 (1992), 3-31.

J. Halberstam, I. Livingston (ed.). Posthuman

Bodies. Bloomington, 1995.

Stephen Heath. Questions of Cinema.

Bloomington, 1981

Bernd Herzogenrath. An Art of Desire. Reading

Paul Auster. Amsterdam and Atlanta, 1999.

Douglas R. Hofstadter. Gödel, Escher Bach. An

Eternal Golden Braid. New York, 1979.

John T. Irwin. American Hieroglyphics. The

Symbol of the Egyptian Hieroglyphics in the American

Renaissance. New Haven and London, 1980.

Anne Jerslev. David Lynch i vore řjne.

Copenhagen, 1991.

Franz Kafka. Letter to the Father. Prague,

1998.

Jacques Lacan. Écrits. Paris, 1966.

-----. Écrits. A Selection. Trans. A.

Sheridan, New York 1977.

-----. Le Séminaire Livre XX: Encore.

Paris, 1975.

-----. 'Vorwort zur dt. Ausgabe meiner

Schriften.' in: Schriften II. Weinheim, 1991.

-----. The Four Fundamental Concepts of

Psychoanalysis. Trans. A. Sheridan. New York, London, 1978.

-----. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book I:

Freud's Paper on Technique 1953-54. Transl. by J. Forrester.

Cambridge, 1988.

-----. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book III:

The Psychoses, 1955-56. Transl. by R. Grigg. New York, 1993.

Christian Metz. The Imaginary Signifier.

Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Trans. C. Britton, A. Williams,

B. Brewster and A Guzzetti. Bloomington, 1982.

Jacques-Alain Miller. 'Suture (elements of the

logic of the signifier).' Screen 18:4, (1977/78), 24-34.

Official Press Kit for Lost Highway. http://www.mike

dunn.com/lynch/lh/lhpress.html

Frank W. Putnam. Diagnosis and Treatment of

Multiple Persona Disorder. New York, 1989.

Chris Rodley (ed.). Lynch on Lynch.

London, Boston, 1997.

Colin Ross. Dissociative Identity Disorder.

Diagnosis, Clinical Features, and Treatment of Multiple

Personality. New York 1997.

Georg Seeßlen. David Lynch und seine Filme.

Marburg und Berlin, 3. erw. Auflage 1997.

Steven Shaviro. Stranded in the Jungle.

(forthcoming book; excerpts can already be found on Steven

Shaviro's homepage; see his chapter 'Intrusion:' http://www.dhalgren.

com/Stranded/18.html

Kaja Silverman. The Subject of Semiotics.

New York, 1983.

Frederick Szebin and Steve Biodrowski. 'A surreal

meditation on love, jealousy, identity and reality.'

Cinefantastique, April 1997. http://www.miked

unn.com/lynch/lh/cinelh.html

'10 Shades of Noir. Film Noir: An Introduction.'

Image e-zine,

htt

p://www.imagesjournal.com/issue02/infocus/filmnoir.htm.

Varma, V.K., Bouri, M., & Wig, N.N. 'Multiple

personality in India: Comparison with hysterical

possession states.' American Journal of Psychotherapy 35

(1981).

David Foster Wallace. Article on Lost

Highway in Premiere, Sept. 1996.

http://www.m

ikedunn.com/lynch/lh/lhpremiere.html

Ron Wells. 'Lost Highway Screenwriter Barry

Gifford.' Film Threat.

http://www.mi

kedunn.com/lynch/lh/lhgifford.html.

Peter Wollen. Readings and Writings: Semiotic

Counter-Strategies. London, 1982.

Slavoj Zizek (ed.). Everything you always

wanted to know about Lacan (but were afraid to ask Hitchcock).

New York, London, 1992.

Slavoj Zizek. Tarrying with the Negative.

Durham 1993.

Slavoj Zizek. The Plague of Fantasies. New

York, London, 1997.

|

At this moment, Fred somehow morphs into

Pete Dayton, a

young mechanic who is suddenly sitting in Fred's cell. Pete's life

is situated in typical Lynchian suburbia, an almost exact replica of

the small-town in Blue Velvet. Similarly to Blue

Velvet's Lumberton, Pete's life is overshadowed by his

connections to the town's Mafia boss, Mr. Eddy. At some point, Pete

meets Alice Wakefield, Mr.Eddy's babe. Within a few minutes, Pete,

although he is still dating his girlfriend Sheila, finds himself

entangled in a sultry love affair with the local Godfather's moll -

a woman who looks like Renee to a hair: whereas Renee was

brunette, Alice is a platinum blonde (if you're thinking of

Hitchcock's Vertigo - double Kim Novak - here, you're right;

Lynch himself had already made use of this 'double' in his Twin

Peaks series). Alice, like Renee, is leading a double life.

Being a member of the porno underworld, Alice, in classic film-

noir-femme-fatale fashion, tempts Pete to commit betrayal and

murder until, finally, a strange encounter at a cabin in the desert

connects the movie's two story strands full circle, or, to be more

precise, full Moebius Strip: Pete disappears, Fred re-surfaces

again.

At this moment, Fred somehow morphs into

Pete Dayton, a

young mechanic who is suddenly sitting in Fred's cell. Pete's life

is situated in typical Lynchian suburbia, an almost exact replica of

the small-town in Blue Velvet. Similarly to Blue

Velvet's Lumberton, Pete's life is overshadowed by his

connections to the town's Mafia boss, Mr. Eddy. At some point, Pete

meets Alice Wakefield, Mr.Eddy's babe. Within a few minutes, Pete,

although he is still dating his girlfriend Sheila, finds himself

entangled in a sultry love affair with the local Godfather's moll -

a woman who looks like Renee to a hair: whereas Renee was

brunette, Alice is a platinum blonde (if you're thinking of

Hitchcock's Vertigo - double Kim Novak - here, you're right;

Lynch himself had already made use of this 'double' in his Twin

Peaks series). Alice, like Renee, is leading a double life.

Being a member of the porno underworld, Alice, in classic film-

noir-femme-fatale fashion, tempts Pete to commit betrayal and

murder until, finally, a strange encounter at a cabin in the desert

connects the movie's two story strands full circle, or, to be more

precise, full Moebius Strip: Pete disappears, Fred re-surfaces

again.

Another specific example of the merging

of inside and

outside apart from the frame-tale (Dick Laurent is dead)

already mentioned, is, most important, the scene in which Fred meets

the Mystery Man for the first time. In fact, the Mystery Man -

simultaneously being inside and outside - can be read at the place

where these (and in fact: all) opposites meet, he is - so to speak -

the twist in the Moebius strip. In Lacan's use of the Moebius Strip,

the place denoting the suture of the imaginary and symbolic in a way

"hides" the primordial cut that instigated this

topological figure in the first place, the cut that is the

unconscious (or, in Lacanian terminology: the real). It is by

suturing off the real that reality for the subject remains a

coherent illusion, that prevents the subject from falling

prey to the real, that is, falling into psychosis. It is no wonder,

then, that the Mystery Man always appears when a change in

personality is close.

Another specific example of the merging

of inside and

outside apart from the frame-tale (Dick Laurent is dead)

already mentioned, is, most important, the scene in which Fred meets

the Mystery Man for the first time. In fact, the Mystery Man -

simultaneously being inside and outside - can be read at the place

where these (and in fact: all) opposites meet, he is - so to speak -

the twist in the Moebius strip. In Lacan's use of the Moebius Strip,

the place denoting the suture of the imaginary and symbolic in a way

"hides" the primordial cut that instigated this

topological figure in the first place, the cut that is the

unconscious (or, in Lacanian terminology: the real). It is by

suturing off the real that reality for the subject remains a

coherent illusion, that prevents the subject from falling

prey to the real, that is, falling into psychosis. It is no wonder,

then, that the Mystery Man always appears when a change in

personality is close.  Here, in the Madison marriage, we have a

routine-version

of this symbiosis. All distance has gone, and, since desire can be

said to be exactly relying on this distance between subject and

object, desire has gone, as well. Being too near to the object of

desire causes anxiety. And indeed, there are also disturbing signs

of something that threatens to undo this imaginary wholeness. First,

there are those strange videotapes. In addition, both Fred and Renee

have an uncanny feeling of being observed; note for example Renee's

facial expression when she finds the first video, which might be

both explained by the fact that she fears that it might be one of

those porn videos she is starring in, and of which Fred does not

know anything, or by the general feeling of being observed, a

feeling that takes shape in the fact that they live close to the

"observatory." The outside literally starts to intrude the

inside, and the threat is emphasized by the deep droning sounds (in

a cinema with a good sound system, the spectators actually can

feel this threat as a uncomfortable feeling in their stomachs

... already in Eraserhead, Lynch had made use of this device,

the constant droning of a ship's engine underlying the whole movie).

Here, in the Madison marriage, we have a

routine-version

of this symbiosis. All distance has gone, and, since desire can be

said to be exactly relying on this distance between subject and

object, desire has gone, as well. Being too near to the object of

desire causes anxiety. And indeed, there are also disturbing signs

of something that threatens to undo this imaginary wholeness. First,

there are those strange videotapes. In addition, both Fred and Renee

have an uncanny feeling of being observed; note for example Renee's

facial expression when she finds the first video, which might be

both explained by the fact that she fears that it might be one of

those porn videos she is starring in, and of which Fred does not

know anything, or by the general feeling of being observed, a

feeling that takes shape in the fact that they live close to the

"observatory." The outside literally starts to intrude the

inside, and the threat is emphasized by the deep droning sounds (in

a cinema with a good sound system, the spectators actually can

feel this threat as a uncomfortable feeling in their stomachs

... already in Eraserhead, Lynch had made use of this device,

the constant droning of a ship's engine underlying the whole movie).

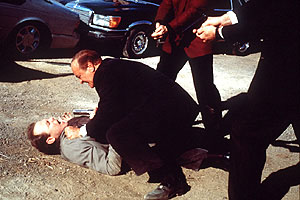

The primal father enjoyed all the women of the tribe, he was the

chieftain, the law-giver, and when his sons killed him, out of shame

the forbid themselves to "have all the women." So, at the

bottom of the law, of the incest taboo, there is the figure of the

One who had been the exception to the rule. In Lost Highway,

this becomes clear in the scene when Mr. Eddy beats and humilates a

driver for tail-gating (

The primal father enjoyed all the women of the tribe, he was the

chieftain, the law-giver, and when his sons killed him, out of shame

the forbid themselves to "have all the women." So, at the

bottom of the law, of the incest taboo, there is the figure of the

One who had been the exception to the rule. In Lost Highway,

this becomes clear in the scene when Mr. Eddy beats and humilates a

driver for tail-gating (