|

|

|

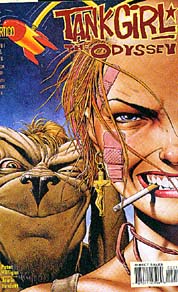

Tank Girl, Anodder Oddyssey: Joyce Lives (and Dies) in Popular Culture Thomas Vogler Other Voices, v.1, n.2 (September 1998)

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas Vogler, all rights reserved; Tank Girl images Copyright © 1995 DC Comics

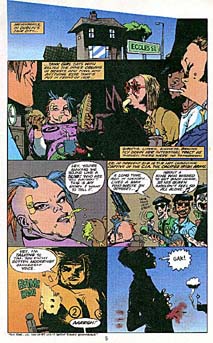

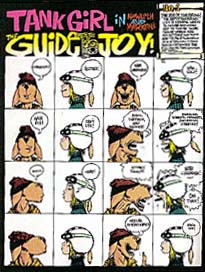

As we all know, Joyce's Ulysses is a comic novel that uses parallels with Homer's Odyssey as a significant element of its formal organization. In his famous 1923 review of the novel, T. S. Eliot called this a "mythical method," and identified it as an especially modern way of achieving form in the chaos of contemporary life, distinguishing it from the familiar literary practice of adding "allusions" as a form of enrichment to a work that could be imagined to exist without them. (1) Joyce and Eliot both extended the use of allusions to the point where there could be no articulate and coherent work without them, collapsing the opposition between work and allusion or text and supplement. Now, at the opposite end of the century, comes another fulfillment of Eliot's prediction that this was "a method others must pursue after Joyce." Like Ulysses and The Waste Land, Tank Girl: The Odyssey is structured by manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity. But this time the context is postmodern rather than modern, and Joyce himself has become part of that antiquity available for use. As the author who did most in the modern period to collapse the distinction between high art and popular culture, only to become elevated to the pinnacle of canonical twentieth-century literature, it is only fair that another collapse of the distinction has been effected using Joyce's work, this time from "below," as one of the most popular international comic series of the twentieth- century has joined its eponymous heroine Tank Girl with Joyce and Homer to create a four-part series. (2) Also remarkable are the wit and skill with which the project is accomplished, especially in the verbal dimension which is at times positively Joycean in its polysemous play with its polytropic heroine.

Tank Girl was nineteen years old at her birth on January 15,

1988, in a run-down bedsit in Worthington, a picturesque village

on England's south coast where old-age pensioners go to die. Her

parents were Jamie Hewlett and Alan Martin, who report that they

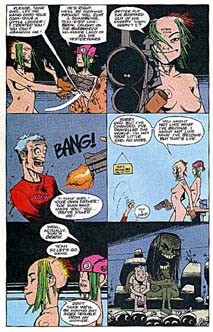

consumed large amounts of cheap beer in an attempt to invent

something radically different for the inaugural issue of a new

magazine. Finally, on Thursday night, around 3:00 am, they came

up with the idea for a female character, an aggro-skinhead woman

from Australia (i.e. from "down under" in sexual, geographical,

national, political, socioeconomic and cultural senses). Tank

Girl was born just in time for the first issue of a magazine

appropriately named Deadline, created by artists Steve

Dillon and Brett Ewins to be a forum for new comic talent, and to

publish the wild, the wacky, and the hitherto unpublishable. Tank

Girl fulfilled their desires in all areas. (3) Starting in 1981 with The Broadcasting Act (prohibiting "as far as possible" anything that "offends against good taste and decency"), followed by the video nasties campaign that culminated in the Video Recordings Act of 1984, and the reactionary views of the Peacock Report on Television and the Government Green Paper on Radio (both supported by the Prime Minister), 1987 had already seen the Obscene Publications Bill (put forward by Tory MP Gerald Howarth in April) and the announcement by Home Secretary Hurd in October of plans to set up a Broadcasting Standards Council, all strongly supported by the ever-vigilant Mary Whitehouse, President of the National Viewers' and Listeners' Association. In this context we can see events like the BBC Channel 4 production of Tony Harrison's v. (where the poet takes on the persona of a graffiti-spraying obscene skinhead) and the launching of Tank Girl as a combined high-culture/popular-culture challenge to such attempts to restrain cultural production.

In her short life Tank Girl has already had several periods of

development. At the very beginning she is a pilot in Australia,

working for some obscure Australian organization, for whom she

undertakes a random series of missions. On one of these-an urgent

assignment to deliver a colostomy bag to an aging Aussie

president-she is attacked en route by a love-crazed monster.

Delay causes the president to dump a load in his trousers at a

large international trade conference. Tank Girl is declared a

criminal, with a million-dollar bounty on her head. Following

this, Tank Girl goes with her friends to live in the outback,

fighting ninjas and monsters and trying to have a good time with

her special friend and main sexual partner, a talking kangaroo

named Booga. In 1989 a dramatic change occurred, when Tank Girl

was moved somewhat against her will to London, for some heavy

postmodernizing. In the second of those issues, "Force Ten to

Ringagooma Bay," The next significant stage in her career comes with Tank Girl's career in the movies. Hewlett and Martin resisted the idea at first, with Jamie calling the proposal "Rambo with tits," but they finally gave in. The movie was filmed June 21-Oct 15, 1994, the first ten days on White Sands Desert in New Mexico and the remainder in an abandoned mine near Tucson, Arizona. It was released March 31, 1995, in the U.S. and on June 16 (!) in the U.K. (5) The film is banal, stupid, and derivative. In its opening scene, a solitary figure (turns out to be Tank Girl) comes riding a water buffalo across a desert. This scene is burlesqued in TGO 2, as one of Tank Girl's male recruits named O'Why delivers a movie pitch to a horde of giant cannibalistic movie producers (The Lestrygonians, led by Lester Gonadian):

As a post-movie series, coming at a particular

moment in the history of its heroine, TGO reflects a

crisis or turning-point in the counter-cultural purity of the

comic, and it attempts to recoup some authenticity after what

seemed a total sellout.

Tank Girl the movie is in fact not very good, though it has a few worthwhile moments. One of the striking differences between the movie and the comic is the move towards a representational mode of "realism" augmented by special effects, as opposed to the fantasy mode of a comic or animated film. One could say that the film is being true to the comic, by bringing it to life, fulfilling it on the screen, producing an effect as if such characters really existed. But this success also marks a failure, and a loss of fantasy effect. The result is a blurring of genre and media distinctions, the same kind of confusion that itself becomes the stuff of tragi-comedy in works like Don Quixote, or Madame Bovary. I'm not suggesting a knee- jerk obeisance to the rules of genre, but whatever gains there might be in postmodern promiscuity are inevitably accompanied by some definite losses. (6) There are a number of seemingly random moments in the Tank Girl movie when brief comic-book-style animated inserts appear, but these seem by their crude contrast only to enhance the "realism" of the filmic mode of representation, which is designed to make something essentially a comic book look as if it were a movie, manipulating realistic people and things in order to make them behave as though they were in a cartoon. But unlike movies like Independence Day and The Nutty Professor that do the same thing, there really is a comic book behind and before the movie Tank Girl. The basic nature of comics, like that of movie cartoons, commedia dell'arte, Satyr plays and the like, is crucially dependent on the fact that they do not attempt any significant degree of realism in their representations. In the last decade the movies have tended increasingly to collapse this distinction, giving us at times inappropriately realistic comics and fantasies, perhaps feeding the already feeble grasp on reality of many viewers. Almost half of Independence Day, the alien-invasion story which was the top-grossing movie of the 1996 summer season was 'filmed' inside a computer, in what are known as "digital special-effects shots," which combine simulated images against a "backplate" (a stock shot, such as a skyline in whatever configuration the director chooses. The technique is employed to make what is essentially a comic book look like a movie, manipulating realistic people and things in order to make them behave as though they were in a cartoon. This trend can be exaggerated parodically in a movie like Natural Born Killers, where the strongest kind of medium manipulation keeps changing into every possible kind of technique, producing a promiscuous concoction that for many viewers goes everywhere and does nothing. By contrast the media mapping of a movie like Roger Rabbit, with its strong visual distinction between "Toon Town" where the comic characters live, and the "real' world, articulates and sustains the differences. Moviegoers in the 1930s and 1940s would almost always see a cartoon with what they called the "main feature." If they were lucky enough to go on a Saturday, they might see an installment in what was called a "serial." Both of these "extra features" were marked by episodic formal structure and a fantasy content that made them distinguishable from the cinema realism of the typical main feature. But the animation technique of the cartoon, with its ability to suspend the laws of material objects in time and space, was thereby distinct even from the serial episodes with their baroque fantasy plots and exotic mise-en- scénes. The movie Tank Girl plays with this difference between comic representation and realistic mimesis too, but tries to overcome it by being a filmed comic, with cartooned humans instead of animated simulations. Where Booga in the comic is a fantasy representation of a talking kangaroo, the "Rippers" in the movie are humans with false ears and snouts and tails. Another way to come at this crucial distinction is to consider some classical precursors for the Booga/Ripper characters. When I look at the Rippers in the movie, and Booga in the comic, I am reminded of Pan, the hairy nature god who was commonly represented both in Egypt and Greece in ancient times under the symbolic form of a goat. Pan was half human and possessed an enormous phallus. His companions were humanoid goat creatures called satyrs. In Medieval times the satyr's goat-like body, cloven hoofs and tail were joined semiotically with the demons of hell, and Pan himself was transformed into the Prince of Incubi, ruler of the lesser demons and devils. In the Renaissance period, as tales of hairy human- like creatures came back to European ears from the wilds of other continents, they were connected with these early accounts under the rubric "homo sylvestris," or man of the woods. (7) In the classical period in Greece, satyrs were honored with their own special scene of representation. We know now that the famous trilogies of the Greek tragedians were actually tetralogies, in which the fourth play (the end-of-the- day feature) was a satyr play, written by the same playwright and using instead of the tragic chorus of Old Men or Libation Bearers or Furies, a chorus of satyrs: half man, half beast, goat-footed, horse-eared, long-tailed. The satyr is ribald, drunken and salacious. His most splendid attribute is his enormous erect phallus, and his play, coming after the tragedy, returned the audience to earth, bringing them back from a metaphysical encounter with fate and the gods to a manifestation of what connects them to the beasts. His presence at the end of the tragic day contributes to a better understanding of the spirit of a Greek theatre which includes both, where the awed silence at the end of the tragic catharsis could be almost immediately followed by the lewd jingle of a satyr's tambourine. The satyr play is bawdy, gross, raucous, insubordinate, but it co-existed with tragedy in order to release the audience into a celebration undefeated by the tragic. (8) Comics are a marginal genre too, but unlike the satyr play they do not share the same audience with serious literature. They exist in a reduced ratio, like animated cartoons to movies in the 1930s, or the comics in newspapers today, a segregated supplement to the "news." The animated film is also comparable to the comic book; with a very few exceptions it is a short thing which until recently the economics and critical establishment of the film industry have agreed to keep in obscurity. Animation is rarely considered worthy of serious critical attention, although this has not always been the case. The hot-house atmosphere of European and Russian modernism in the 1920s and early 1930s fostered collaboration and mutual inspiration between different art forms and film, including animation, was seen and discussed as part of that movement. But as the narrative fiction fi1m became the prevailing form of cinema around the world, and Hollywood grew to dominate economically and culturally in the post-war West, animation came to be defined by the Disney model, the cartoon. And following Disney's audacious gamble on the animated feature film, the cartoon was primarily identified as entertainment for children, a non-serious area for most film critics. Cartoons were also widely used for instructional and propaganda purposes, which further contributed to their lowly artistic status. (9) If we seek a more theoretical understanding of these marginal works, we can find in Bakhtin some useful notions that help to explain how a late twentieth-century product like Tank Girl can embody all the major features of the Greek satyr performances, and can share those features with works by writers like Joyce and Rabelais. As Michael Holquist points out, Bakhtin's book on Carnival is "about the subversive openness of the Rabelaisian novel, but it is also a subversively open book itself," because its central concept of "grotesque realism" is a direct and specific inversion of the categories and artistic values invoked in the thirties to define Socialist Realism. (10) According to Bakhtin, "Rabelais' basic goal was to destroy the official picture of events.... He summoned all the resources of sober popular imagery in order to break up official lies and the narrow seriousness dictated by the ruling classes. Rabelais did not implicitly believe in what his time 'said and imagined about itself'; he strove to disclose its true meaning for the people" (439). Bakhtin's work emphasizes the predominant role in Rabelais played by a material bodily principle represented by exaggerated images of the body in connection with food, drink, elimination and sexual activity. He calls this "grotesque realism," and argues that it represents a profoundly positive emphasis, since the body is universal, panhuman in its representational scope, opposed to more limited and specific private and egotistic aspects of existence. As the ghost of Tank Girl's Mother says, "I know it sounds a little undignified. But ... we're born between piss and shit ... so we don't really have much to be proud about, do we?" The essential principle of grotesque realism is the lowering of all that is spiritual, ideal, and abstract, shifting focus and value to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body in an indissoluble unity. Its main stress is placed on those parts of the body that are open to and interactive with the outside world- the open mouth, the genital organs, the breasts, anus, nose-and on the effluvial intermixing of the body's inside and outside through acts of taking in (eating, drinking, sexual union) and discharge: flatulence, defecation, urination, ejaculation, menstrual blood, nasal discharge, sweat, tears. According to Bakhtin, Rabelais represents the rebirth of a mode of grotesque imagery that can be found in the mythology and in the archaic art of all peoples, including the Greeks and Romans of the preclassic period. It was during this period that the grotesque was expelled from official public art to live and develop in certain 'low' nonclassic areas. As Tony Harrison's Silenus puts it: "They set up a contest, rigged from the start, / to determine the future of 'high' and 'low' art. They had it all fixed that Apollo should win / and he ordered my brother to be flayed of his skin" (125). Bakhtin places great importance on

institutionalized language in his study, and notes that when

activated the grotesque concept of the body generates oaths,

curses and language of abuse rich with body imagery. It thus

contributes to that conflicting multiplicity of languages which

he associates with cultural health and calls "heteroglossia," as

opposed to the monologism that most official cultures seek to

enforce. His notions of dialogism and polyphony are closely

related to the concepts of heteroglossia and carnivalization that

constitute his visionary sense of language (whether written,

spoken or internal monologue) as the rich field of an enormous

variety of conflicting and variant languages, ranging from the

literary and poetic through specialized jargons of all sorts to

the subliterary, the vernacular, the obscene and primitive.

Bakhtin represents the middle ages as an era of "monological"

control and repression, not unlike the kind of official culture

that dominant forces in Anglo-American politics were pushing for

with renewed strength in the 1980s. He argues that Rabelais

"dialogizes" that culture by producing the oppositional voice of

"carnival" which has the effect of undermining authoritative

utterance. The effect is not to replace a 'high' cultural and

literary level of language with a 'low,' but to achieve a

polyphonic range that combines all levels.

Bakhtin's theory of carnival is also an example of "counter-narrative." Were I writing this for publication in the U.S., or for a cultural studies venue, I would be obligated here to indulge in some heroic rhetoric of cultural opposition, invoking concepts such as dominant constructions and effective dissidence from oppositional cultural sites, or marginal hegemonic subversion, or counter-hegemonic narrative transgression, and most of my readers would already have made up their minds either that effective counter-narrative is universal and inevitable or that it's absolutely impossible, invoking Adorno and the heirs of his theory of what he called the "consciousness industry." My lower-key notion is based on the rather commonplace observation that people seem to achieve an understanding of themselves and the world through narratives- narratives purveyed by parents, schoolteachers, newscasters, 'authorities,' and all the other authors of what we take to be sources of common sense. As Hayden White points out, such narratives mediate a world that "does not come to us already narrativized and coherent; the construction of narrativizing discourse serves the purpose of moralizing judgments." (11) They provide a version of reality whose acceptability is governed by convention and 'narrative necessity' rather than by empirical verification and logical requirements. On the individual level, our accounts of happenings in our own lives are eventually converted into more or less coherent autobiographies centered around what we like to call a self acting more or less purposefully in a social world. On the collective level Social realities are also worked out through narrative. Eventually a number of separate, individual stories get combined into a whole of some sort, variously called a 'culture' or a 'history' or, more loosely, a 'tradition.' Counternarratives are, in turn, the means by which individuals or groups seek to modify or contest that dominant reality and the network of assumptions that supports it. Counter-narratives are not necessarily subversive; they often combine to produce a rich heteroglossia of narrative alternatives. Consider Batman, in many ways a counter- narrative-or counterpart narrative- to Superman. Where Superman is a creature of the daytime and the sky, akin to the sungod Apollo, Batman is nocturnal, rodential, feminized, companion of Hecate and the moon. There is a reversal of inside/outside, too: Superman is super at the core, but puts on wimpy externals to become mild-mannered Clark Kent. Batman is Bruce Wayne, human at the core, who dresses up to his role rather than strips down to it. But both Superman and Batman-along with Captain Marvel, Captain America, and all the other mysterious muscle-bound, masked mercurial tribe- can be identified as "recuperated" Satan figures, working for law and order. Robert Hughes traces their iconography in detail, and finds in them the "last flicker of Satanic omnipotence and Luciferian, if prognathous, beauty." (12) So in the U.S. in the late 1930s, Anti-Christ, the wonder-worker, went to work in the form of Superman for J. Edgar Hoover, defending democracy in what we might call a counter-counter-narrative. (13) James Joyce's Ulysses is without doubt one of the most elaborate and intensive counter-narratives ever written-almost-in the English language. With its canonization as a great work of English Literature, it's easy to forget that much of the force of the novel is conspicuously hostile to the notion of high literature in general, and to English literature and the English language in particular. The book functions in many ways as an act of literary defiance, directed against a whole battery of artistic, social, historical assumptions and practices, so that its original value was in part the way it transcends and indeed proffers alternatives to received ideas as it defies them. TGO is like Ulysses, but in being truly like it, in being a counter-narrative, it is also counter to it Joyce's introduction to the character of Odysseus came when he read Charles Lamb's Adventures of Ulysses at the age of twelve, and was inspired to choose Ulysses as the subject for an assigned essay on the topic "My Favorite Hero." Already, it would seem, the practitioner of "silence, exile and cunning" was drawn to the "Ulyssean" (defined in the OED as "resembling Ulysses in craft or deceit), anticipating the verdict he would deliver later, that "the whole structure of heroism is, and always was, a damned lie." (14) Joyce's choice of hero was indeed an odd and distinctly anti-heroic one by conventional standards, for the Odyssey, as a heroic quest for home and hearth and wife and family and faithful dog Argus is already in important ways an anti-heroic counter-narrative to The Iliad as war epic. As early as the fifth century Odysseus had become the target for a stinking chamber pot in Aeschylus's parodic satyr play The Bone Gatherers. Bakhtin points out that

A typical scholarly view of Odysseus as inadequate hero can be found in L. R. Lind's Introduction to his translation of Vergil's Aeneid:

for Joyce and Tank Girl, these negative qualities might be much more appealing than their opposites. Note Lind's distaste for bodily functions; presumably his ideal hero would be a killing machine that never ate, slept or had sex. Lind's choice for a hero is the good Christian choice, pius Aeneus, the same that Dante had chosen to guide him through hell and purgatory. His dislike for Odysseus seems to be that he is having too much fun, and the wrong kind of fun. It is not too different from the early Christianity that Bakhtin claims condemned laughter. Bakhtin notes for example that Tertullian, Cyprian, and John Chrysostom preached against ancient spectacles and theater, especially against the mime and the mime's jests and laughter. John Chrysostom declared that jests and laughter are not from God but from the devil. Only permanent seriousness, remorse, and sorrow for his sins befit the Christian." Odysseus had already started to get a bad reputation long before Christianity and its strictures against the flesh. Although he is represented as an admirable character in Sophocles' early play Ajax, a model of humane and civilized conduct, he is considered beneath contempt by Ajax himself and his followers. Some forty years later, in his Philoctetes, Sophocles presents an Odysseus closer to Ajax's view, a machiavellian operator who glibly lies to accomplish his goals, a coward, a knave, and an unsuccessful one at that, whose mission has to be completed by the god Herakles. By the time of Euripides' Hecuba, we have perhaps the most detestable portrait of Odysseus in the whole classical tradition, a man who resembled the unscrupulous politicians of the late fifth century BC, exhibiting all the attributes that Euripides detested in the contemporary political scene: argumentative, ungrateful, callous, chauvinistic. It was about the same time that Odysseus, along with Herakles, became a very popular figure for Greek comic writers, and a popular comic subject for visual artists as well, who took delight in representing burlesque versions of his adventures. Joyce amplifies the anti-heroic potential by making his Odysseus figure a noncombative Irish Jew, who not only doesn't slaughter any suitors, but also considerately stays away from his house to provide the opportunity for his wife's infidelity. When he finally does get home, he rejects the Odyssean revenge and violence against the suitors. To make Odysseus Jewish in Ireland in 1904, was still a daring creative leap in an age of ugly ideologies where imperialism, racism, militarism and misogyny were raised to the level of secular religions as the ethical orthodoxies of the day. And to make him effeminate ("the new womanly man," as Mulligan calls him in Circe) was not only to violate the military imperative, but to make him even more authentically 'Jewish' in a world that increasingly linked Jews with women and blacks and orientals as genetically inferior beings. To make Tank Girl a counter-hero/ine in 1988, only two years after Margaret Thatcher posed for her tank girl photograph, is to engage in a similar strategy of ideological confrontation, but it is not enough to have a hero gendered feminine who drives a tank. She must break every establishment rule for behavior from whatever gender, and defy all feminist protocols for politically correct feminism; and she must be presented in a comic that breaks all the conventions of the form. And when even those characteristics become commodified-first her semiotic "transgression" reduced to a desirable consumer item, a style of consumption, then aped by an even more extreme commercial debasement in the form of a movie-even more extreme measures are called for. In the usual critical view, high art renews itself by stooping to borrow from lower popular sources, advancing "through unfastidious cross-fertilization from obscure and popular genres." (17) Tank Girl's bold strategy in TGO is to invert this model, adopting a tactic of fastidious cross-fertilization from well- known literary masterpieces, with herself as offspring. The result is an inversion of the inversion, a creation that makes the line between high and low culture difficult to draw, and eliminates the kind of transgressivity that reinforces the opposition between high and low altogether, as did Joyce. (18) To move now to some more specific observations

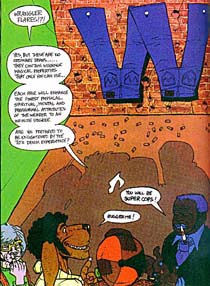

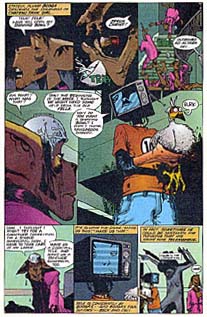

on the TGO series, it should be emphasized that the

Homeric Odyssey is included along with Joyce's text as

material for parody and intertextual play. Where Joyce has Molly

weave and unweave a web of unending 'text' (from textus,

past participle of texere, to weave), Booga eludes his

suitors by excusing himself to go do some sewing. Odysseus's

faithful dog Argus becomes Tank Girl's pet Koala, also named

Argus. Tank Girl and her crew actually visit the underground

world of the dead, and the Sirens in TGO are closer to

those in Homer, surrounded as Circe warns, by rotting piles of

bones. But such "closeness" is infrequent and not really to the

point in a work where the Telemachus figure is extrapolated even

beyond Stephen Dedalus, to become a humanoid television set named

Tele, who is "made not begotten, from bits of old televisions,

computers, corpses of washed-up surfer boys."

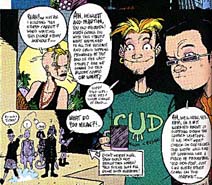

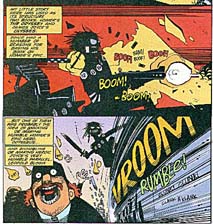

Like the names, the adventures of Tank Girl tend to be generated through the effects of an aleatory polysemy operating at the level of the signifier, rather than being generated through structural parallels with Joyce and Homer. Peter Milligan, the writer brought in for TGO, is a true "voyeur of the name," ("ici le voyeur de son nom, le voyeur en son nom, le voyeur depuis son nom,"), most happy when the accident of a name can generate a new plot situation with only trans-nominal similarity with Joyce or Homer. (20) For example, the "Wondering Rocks" (an episode not in Homer, since his Odysseus goes the other way) become the "wondering Ricks," characters who are twins, somewhat like Tweedledum & Tweedledee in Lewis Carroll. They clash too, but like siblings instead of like rocks. Among the most absurd is the Aeolus episode, where the "winds" of the windy city of Troy, transformed by Joyce into the "hot air" of Dublin discourse, become "farts that bring dead things back to life," the "flatutherapy" or "Resurrection Wind" that is the great life's work of Dr. Albert Einstein Olus, known as A. E. Olus. Thus we have "Aeolus," with a hint of AE (and AEIOU) together with "olus," suggestive of the Latin olere, to smell. (21) Eumaeus becomes Old Eugene Mouse, the barman at the Swineherd Inn, who persuades Tank Girl and her crew to dress like Charlie Chaplin (i.e. "debasement" in the guise of a movie tramp). "Circe" becomes "Sir Rupert Sir ... Otherwise known as Sir Sir," head of Swine Television, who speaks with an Australian accent ("G'day. I'm gonna make you blokes stinking rich.") and uses his wealth to animalize humans. The name of Tony the Blazer is an echo of Joyce's Blazes Boylan A suitor of Booga/Molly/Penelope, his status as a big-time producer also makes him a "suit" in contemporary slang. The "Tony" echoes Homer's Antínoös, who is the first suitor to die by Odysseus's bow, as Tony the Blazer is the first to die by the blow of Tank Girl's hand.

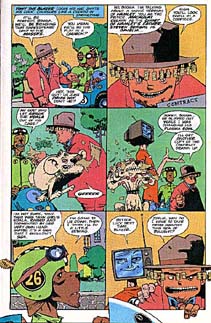

The finale of TGO thus differs radically from Joyce's

pacific transformation of The Odyssey, but it also

diverges from Homer, who submits his Odysseus to several books of

patient abasement and careful planning before allowing him the

catharsis of wholesale slaughter. Tank Girl's plan is formed

instantaneously: "I've obviously got to be really cunning. So I

thought we might use Tank to blow one of the walls of the house

down, and then we can run in, setting fire to the furniture,

smashing ornaments, and mutilating people." Where the extremely

graphic violence in Homer has a dignified, almost ritualistic

quality ("Like pipes his nostrils jetted / crimson runnels, a

river of mortal red, / and one last kick upset his table /

knocking the bread and meat to soak in dusty blood."), the

ludicrous extremes of graphic violence in TGO become

parodic, a simultaneous indulgence in and send up of violence-as-

entertainment. (22)

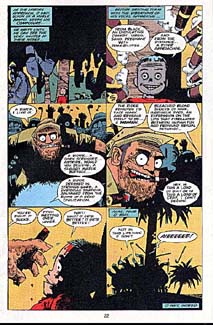

Many of the "adventures" are only obliquely

hinted at in TGO (e.g. Nestor, Proteus, Scylla and

Charybdis, Hades) while others are developed much more fully. One

of the more semiotically complex and interesting ones is

identified in the text as "Island of the Oxen of the Godson,"

starting with an inversion of the "Sungod" Helios and including

an inversion of father/son from the Godfather (yet another

movie allusion). The island (perhaps Sicily?) is run by a mafioso

"Godson" named Giorgio, who stocks it with 'animals' that are

humans dressed in animal costumes. Dismayed by the mistreatment

of animals in the circus (visual hints of Fellini's Clowns

in the graphics) he "decided that the Mafia should move into the

holistic non-animal circus business," so in order to indulge his

sentimental concern for the animals, he has forced these humans

to undergo the mistreatment in their place. While Tank Girl is

having a two-week sex marathon in the tank with O'Madagain, her

crew starts eating the "animals," and the Mafiosi-grotesque

caricatures of the movie caricatures- come in with guns blazing.

In TGO the role of the gods is taken by

Tank Girl's dead but constantly intervening mother, who appears

at crucial times, rising high above the horizon like Goya's

version of Saturn devouring his son, to affect the plot ex

machina. She is also like Stephen Dedalus's mother in

Ulysses, whose Chthonic off-stage presence is always in

the back of Stephen's mind, ready to make an appearance, as she

finally does in Circe when she "rises stark through the floor

in leper grey.... Her face worn and noseless, green with grave

mould ... a green rill of bile trickling from a side of her

mouth" (24) It turns out that

Tank Girl's mother (referred to as "Motherfather" at one point)

is tormenting Tank Girl and her crew because she died before her

husband. She wants him dead so he will have to join her in Hades,

where she can torment him through eternity. At the beginning of

TGO Tank Girl kills an "omniscient narrator" in the guise

of James Joyce, as if taking literally one of Harold Bloom's

Oedipal "revisionary ratios" in order to relieve anxieties of

influence. At the end, in order to placate her mother, she

chooses to kill her fictively "real" father, who turns out to be

O'Hell (disguised from the beginning as one of her "recruits") in

order to placate her mother. As she prepares to shoot him, she

asks: "Why disguise yourself and hang around us?"

Tank girl is an enormously trendy consumer item among adolescents, and counter-hegemonic narrative transgression from marginal post-colonial sites is an equally trendy consumer item among leftish leaning academics and students. I would really like to believe that a product like Tank Girl can be a modern example of Bakhtin's carnival, and combine having fun with doing serious progressive cultural work. But can a comic book that contrives a plot so as to include an add for Wrangler jeans really be subversive? Is there any place in a culture industry that ranges from Homer to Joyce to Tank Girl for an effective counternarrative or counter- culture discourse? Paul Mann puts the case with what he calls a "brutal simplicity":

I suspect that some of the bitter cynicism in these remarks is the result of a passionate desire that this were not the case, and that is a desire I share. But the real "counter" in counter-culture may always turn out to be the counter in the store, on which you place your money, time after time, to buy basically the same commodities. No work can successfully resist the commodity status of marketing success, and the inevitable mainstreaming of counterculture, when the transformation of rebellion into money is the fundamental operation of our pop-cultural machinery and the commercialization of deviance has become the universal theme of American culture.

Author's Note: An earlier version of this essay was given as an illustrated presentation to the "Homer and Popular Culture Conference" at Santa Cruz in November, 1995, and expanded versions were given at the "Re: Joyce" conference at Dundee in July, 1996 and the "Classical Joyce" International Conference at Rome in June, 1998. I am grateful to the organizers of those events, Mary-Kay Gamel, Julian Wolfreys, Cheryl Herr and R. B. Kershner, and indebted to the helpful discussions they generated.

Endnotes: (1) See "Ulysses, Order, and Myth" in Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot. Ed. Frank Kermode (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), 177. (2) Jamie Hewlett and Alan Martin, Tank Girl: The Odyssey (New York: DC Comics, Deadlines Publications Limited, 1995). Peter Milligan is credited as writer, Jamie Hewlett as artist, Nathan Eyring as colorist and Annie Parkhouse as letterer. The series came out over a four- month period: No. 1 in June, No. 2 in July, No. 3 in August and No. 4 in September. References to the whole series will be identified in my text by TGO, and references to specific volumes by TGO plus the volume number (TGO 1, 2, 3 or 4). (3) Much of this information was culled from an "Unauthorized Biography" of Tank Girl and other information that can be found at the Tank Girl web site < http://www.dos.qmw.ac.uk/~bob/stuff/tg/> run by Bob Rosenberg (bob@dcs.gmw.ac.uk). (4)The photograph was taken while Thatcher was visiting British troops in West Germany. It was recently reprinted in Roy Strong, The Story of Britain (London, 1996) and in the Times Literary Supplement, September 20, 1996, p. 9. The very day Tank Girl came to life the Daily Mail announced that Tory MP David Sumberg was demanding an inquiry and filing a complaint to Education Secretary Kenneth Baker because "crude, obscene and offensive" poems by Tony Harrison had been required A-level reading for their 16-year-old daughter. This came after two months of public altercation prompted by the BBC Channel 4 broadcast of a video production of Harrison's poem v. (4 November 1987). Details of the Harrison BBC controversy can be found in Tony Harrison, v. (Newcastle upon Tyne, 1989), a special edition of the poem by Bloodaxe Books .

(5) Rejected by Stephen Spielberg's

production company (rumored to have declared it "too hip"), MGM

turned to Rachel Talalay (who had produced the cult trash films

Hairspray, and Cry Baby for John Waters before

becoming respectable with Freddy's Dead: The Final

Nightmare). After huge public auditions were held as a

publicity stunt in New York, London and Los Angeles, the role was

turned down by Emily Lloyd (who refused to shave her head) and

given to ingenue Lori Petty. The "Rippers" or kangaroo-men

included Ice-T, as T-Saint and Jeff Kober as Booga. The evil

villain Kesslee was played by Malcolm McDowell. Rat face by Iggy

Pop. A very mixed soundtrack included music by Hole, Sonic Youth,

Veruca Salt, Luscious Jackson, Portishead, Bush, Belly, Bjork,

Stomp, Joan Jet and Paul Westerberg, Ice-T, Devo, L7, Magnificent

Bastards, Beowulf, and others. Most of the parts that were in

the least true to the ribald spirit of the comics were cut (e.g.

drug use, kangaroo shagging). Expository parts were cut, and

replaced with voice-overs. Out-takes are available of some of

the cut parts (very low quality, but interesting) for $10 from

(6) A scene in Bladerunner

offers itself as an allegory of the collapse of the distinction I

am trying to make here: Deckard is in Sebastian's doll-filled

studio, looking at one, trying to tell whether she's human or

not. The dolls in that scene are "real" dolls, and also function

as dolls in the fictive reality of the film. What the

audience sees then is a real human (actor) playing the rôle

of a "replicant" who is pretending to be a human who is

pretending to be a doll. As it turns out there's no real

difference between the order of human and doll (or "replicant")

in the movie, except perhaps that the ones we know are replicants

are more human than the ones we think might be human.

(7) See Edward Tyson M.D., Orang-

Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie

(London, 1699).

(8) Tony Harrison has produced a

satyr play called The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, based on

the only surviving Sophoclean fragment of a Greek satyr play. In

his usual way, Harrison turns this into a work dealing with the

clash between high and low art, and includes much rhymed self-

definition. Here are some typical lines from the satyr and master

of ceremonies called Silenus: "Satyrs in theatre are on hand to

reassess / doom and destiny and dire distress. / Six hours of

tragedy and half an hour of fun. / But they were an entity

conceived as one. / But when the teachers and critics made their

selections / they elbowed the satyrs with embarrassing erections.

/ Those teachers of tragedy sought to exclude / the rampant half-

animals as offensive and rude." Tony Harrison, The Trackers

of Oxyrhynchus (London, 1991): 61. The Harrison production

equipped its satyrs with enormous phalloi based on Greek models.

Tank Girl does not have an "embarrassing erection," but she has

her tank; and when she sits astride the barrel of its large gun

she is a convincing illustration of Lacan's dictum that "the

phallus is not a penis."

(9) My comments here are limited to

the Anglo-American context. The cultural status of film animation

is different in Europe, and more different still in Japan, where

the anime (as the fans call them) are part of mainstream

culture. Feature films, television series, or "straight to video"

releases offer graphically explicit fantasy violence and sex,

ranging from comic romances of high school students to

pornographic demons with penises larger than skyscrapers.

(10) Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais

and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Blomington: Indiana

UP, 1986, xvi.

(11) Hayden White, The Content

of the Form (Baltimore, 1987): 24. "What wish is enacted,

what desire is gratified, by the fantasy that real events are

properly represented when they can be shown to display the formal

coherency of a story? In the enigma of this wish, this desire, we

catch a glimpse of the cultural function of narrativizing

discourse in general, an intimation of the psychological impulse

behind the apparently universal need not only to narrate but to

give to events an aspect of narrativity" (4).

(12) Robert Hughes, Heaven and

Hell in Western Art (New York: Stein and Day, 1968): 281.

(13) In the late 1980s,

contemporaneous with the rise of Tank Girl, the Batman persona

underwent a counter-narrative transformation, and the 1988

Batman: The Movie broke every box-office record in the

books. Sparked by Frank Miller's enormously popular Batman:

The Dark Knight Returns (1986) the Batman was reborn as a

construct of the new period, and Gotham City transformed into a

postapocalyptic scene of urban decay a là

Bladerunner. Dennis O'Neil, who has edited Batman

for Marvel comics since 1986, commented that when he took over

Batman "seemed to be much closer to a family man, much closer to

a nice guy. He seemed to have a love life and he seemed to be

very paternal towards Robin. My version is a lot nastier than

that. He has a lot more edge to him." Roberta E. Pearson and

William Uricchio, eds., The Many Lives of the

Batman,(London, 1991): 19. The "original" Batman, created by

artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger in 1939, was strongly

indebted to the movies (The Mark of Zorro , 1920; The

Bat Whispers, 1930), but behind those influences lay earlier

creations like Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes and still

earlier ones like Edmund Dantes, Hugo's "dark avenger" who had

such an impact on the young Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of the

Artist.

(14) James Joyce, Letters of

James Joyce Vol. II, ed. Richard Ellmann (New York, 1966):

81.

(15) The Dialogic

Imagination. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and

Michael Holquist. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1981, 54.

(16) The Aeneid

Bloomington, Indiana UP, 1963, ix-x.

(17) R. B. Kershner, Joyce,

Bakhtin, and Popular Literature: Chronicles of Disorder

(Chapel Hill and London, 1989): 166.

(18) For the opposite approach, an

attempt to fertilize the low from the high and make it highbrow,

see the 1977 Marvel comic version of The Iliad, a dreary,

humorless attempt to make the comic into a "literary epic."

The Iliad by Homer, Marvel Comics Group ( New York, 1977).

(19) The representation of "Tele"

may also owe something to Australian lore. The outlaw Ned Kelly

(a late-nineteenth century country boy of Irish convict ancestry)

operated in an armored suit of steel made from plowshares, and

became famous for his successful defiance of the police and

colonial authorities. The square head covering of this suit is

featured in a 1960s series of paintings by Sidney Nolan, and the

large black-edged box has an empty space-like a blank TV screen-

where the face should be

(20) For "voyeur of the name" see

Jacques Derrida, Signésponge / Signsponge (New

York, 1984): 7.

(21) Is there some universal

connection between mad scientists and old farts? The Nutty

Professor, one of the top moneymakers of the U.S. 1996 summer

movie season, was aptly described by Louis Menand as

"essentially a movie about-let us not mince words, my fellow

Americans-farting." The Eddie Murphy Nutty Professor is a

remake of the 1963 Jerry Lewis picture, technically superior in

terms of acting and photography, but still no more than a

recycling of the same infantile jokes. "Hollywood's Trap," in

The New York Review (September 19, 1996): 4.

(22) Homer, The Odyssey,

trans. Robert Fitzgerald (New York, 1963): 409.

(23) The cultural taboos on

menstruation have clashed with Joyce's version of Ulysses

too, with its frequent insistence on this function of the female

physiology. Joseph Strick has described the outrage of the

censors at what they took to be Gerty's holding up of a menstrual

pad in the Circe section of his film version of Ulysses in

an oral presentation given at the "Joyce and Culture" Conference

at Irvine, California, June 30, 1993. The male reactions (IRA

leaders as well as prison guards and public officials) when

thirty women prisoners at Armagh joined the infamous "dirty

protest" in February of 1981 were equally extreme. See Allen

Feldman, Formations of Violence: The Narrative of the Body and

Political Terror in Northern Ireland (Chicago, 1991), and

Begoņa Aretxaga, "Dirty Protest: Symbolic Overdetermination and

Gender in Northern Ireland Ethnic Violence," in Ethos

23:2, 123-147.

(24) James Joyce, Ulysses,

ed. Hans Walter Gabler. New York: Vintage,1986, 473-74.

(25) Paul Mann, "Stupid

Undergrounds," in Postmodern Culture 5:3 (May 1995)

Aretxaga, Begoña. "Dirty Protest:

Symbolic Overdetermination and Gender in Northern Ireland Ethnic

Violence." Ethos 23:2, 123-147.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His

World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana UP,

1986).

Derrida, Jacques. Signéponge /

Signsponge. Trans. Richard Rand. New York: Columbia UP,

1984.

Eliot, T. S. "Ulysses, Order, and Myth."

Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot. Ed. Frank Kermode. New

York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

Feldman, Allen. Formations of Violence: The

Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern

Ireland. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1991).

Harrison, Tony. The Trackers of

Oxyrhynchus: The Delphi Text 1988. London, Boston: Faber and

Faber, 1990).

Harrison, Tony. v. Newcastle upon Tyne:

Bloodaxe Books, 1989.

Hewlett, Jamie and Alan Martin. Tank Girl:

The Odyssey. New York: DC Comics, Deadlines Publications

Limited, June (No. 1), July (No. 2), August (No. 3), September

(No. 4), 1995. Peter Milligan is credited as writer, Jamie

Hewlett as artist, Nathan Eyring as colorist and Annie Parkhouse

as letterer.

Homer, The Odyssey. Trans. Robert

Fitzgerald. New York: Doubleday, 1963.

Joyce, James. Letters of James Joyce Vol.

II. Ed. Richard Ellmann. New York: Viking, 1966.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. New York:

Vintage International, 1990.

Mann, Paul. "Stupid Undergrounds"

Postmodern Culture 5:3 (May 1995)

Menand, Louis. "Hollywood's Trap." The New

York Review , September 19, 1996.

R. B. Kershner, Joyce, Bakhtin, and Popular

Literature: Chronicles of Disorder. Chapel Hill and London: U

of North Carolina P, 1989).

Robert Hughes, Robert. Heaven and Hell in

Western Art. New York: Stein and Day, 1968.

Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio, eds.,

The Many Lives of the Batman. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Rosenberg, Bob. Strong, Roy. The Story of Britain. New

York: Fromm International, 1997.

Tyson, Edward, M.D. Orang-Outang, sive Homo

Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie. London, 1699.

White, Hayden. The Content of the Form:

Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins UP, 1987.

|

Supporting Sites: |

Her birth came a little over a year after the Prime Minister had

posed for her famous photograph driving a tank, and it coincided

with a momentous point in the Thatcherite era, with its

relentless attempts to bring the press and media under tighter

control.

Her birth came a little over a year after the Prime Minister had

posed for her famous photograph driving a tank, and it coincided

with a momentous point in the Thatcherite era, with its

relentless attempts to bring the press and media under tighter

control.