|

In Extremis: Hergé's Graphic Exteriority of Character Amanda Macdonald Other Voices, v.1, n.2 (September 1998)

Copyright © 1998, Amanda Macdonald, all rights reserved. Images copyright © Casterman.

Reversing the terms of my subtitle, I might have proposed the subject, "Hergé's characteristic exteriority of graphemes", indicating by this propositional reversal that the possibility of chiasmatic relations between notions of "character" and notions of "the graphic", in Hergé's Tintin corpus, consitutes the main focus of this essay. Hergé, himself, has been known to offer a much less cumbersome assertion of the relatedness of characters and graphics, but a somewhat less explicit one, in describing the care with which he formed the script used to render the verbal elements of his Tintin albums: it was crucial for him that the verbal line work as a graphic echo of the image line. Hergé's line is, of course, known in the francophone world as "la ligne claire"-the "clear", "clean" or even "plain" line, we might say, in English-and designates a substantial generic tradition flowing from Hergé's example, within the larger francophone tradition of bande dessinée(BD) albums [1] (Edgar Jacobs and Ted Benoît being two of the more famous successors to la ligne claire in the realm of Francophone graphic novels). [2] Hergé's concern to match the scripted and the drawn line cannot be construed as simply a matter of aesthetic harmony for the BD pioneer. [3] In "Comment naît une aventure de Tintin" ("How a Tintin adventure is born"), Hergé stresses the generative relation between the two functions that he refers to as "texte et dessin" ("text and drawing"): "texte et dessin naissent simultanément, l'un complétant et expliquant l'autre". [4] His avowal of the importance of graphic harmony between word and image can be understood in relation to some of the main preoccupations of BD criticism, serving as a reminder of the fact that bande dessinée is a genre that, by virtue of its making both word and image graphic, raises interesting questions about the relations between two systems often taken to be at war, in either cultural or semiotic terms. More particularly, and this is the first (and least concerted) argument of two elaborated in this paper, Hergé's image- word practice allows us to see that the principal metaphor of a certain kind of semiotics, the metaphor that proposes "language" as a figure for all systems of meaning, need not be viewed as playing into a logocentric discourse subordinating all other systems to that of the verb and its strong forms of semantic governance: for to speak of "language", in the context of a discussion of bande dessinée, is to speak of a system deriving from drawing. Although Hergé describes the genesis of his dual system in terms of an equal partnership, the account from which this description was taken commits almost no time at all to the process of inventing word text, and leaves one to understand that the image line preceedes the word line in the production of any album, such that it is the word line that must accommodate the iconographic line, not vice versa. A pun that can be made in both English and French, a word-play turning equally well on "character" or "caractère", may be produced out of considerations of the workings of Hergé's graphic topos to link the question of word- and-image relations to that of the representation of the human. This pun suggests that the fundamentally "like" graphic elements from which Hergean words and images are formed share the status of "character"/"caractère", namely the status of "distinctive mark", and that, within the Hergean bande dessinée, the formation of these marks into both words and images "draws" both the logographic and the iconographic into the task of constructing "character", in the sense of "distinctive human-like figure" or "personage" (I will say something, in a moment, about the neologism "logographic"). These two broad understandings of "character"-the elemental and the complex, the materially available and the semantically constituted-when articulated in discussion of Hergean textuality, enable not only an inflected understanding of the issue of word- image relations, but of what the relations between the materiality and the abstraction of the semiotics of personage might be. Once again, the exploration of this problematic is assisted by consideration of an interesting coincidence of language: on the one hand, the French for a drawn line-the elemental mark of any drawing-is "trait" (the ligne claire might have been the trait clair); on the other hand, in both French and English, the elemental behavioural quality of a personage is a "character trait". Using this term, trait, to rehearse two of the basic points made so far, we can make two reformulations: firstly, that in Hergé's Tintin corpus the verbal and the imaged are made of the same "trait"; secondly, that the entirely visible, graphic character and the largely conceptual personage character are also both made of "traits". [5] It becomes very clear why it is important to propose the term "logographic" to designate the verbal function of Hergé's art, instead of following normal usage as does BD commentary: to refer to "the verbal", to "writing", to "speech" or to "dialogue" is to fail to make plain the fact that the materiality of the word in the Tintin corpus is a drawn materiality with graphic properties. [6] The term is useful, too, in its accommodation of the fact that Hergé's dialogue is almost entirely written speech: the bande dessinée obliges any speech to be written, making the term "speech" descriptively inadequate; conversely, Hergé's work generally uses the writing function offered by bande dessinée to represent speech, hence my dissatisfaction with the term "writing". Nothing in the term "logographic" precludes reference to the occasional temporal indicator ("Two days later"), or to the not infrequent representation of extracts from printed documents, yet it permits generically exact reference to the particular unvoiced dialogue of Hergé's system, and insists on the drawn property of all wording. The term, of itself, effectively affirms my first principal argument, in that it makes clear the fact that the logos does not exist before or independently of the iconic, since what we are dealing with is an image-word. It should be added that, in a BD system where there is virtually no explicit narration, the writing of speech, writing that is made of the same graphic stuff as imagery, must have a crucial role in the process of characterisation. This last point foreshadows my second principal argument, one that will require more space than the first, and it concerns the notion of character. "Character", in the broadest sense given to it by general usage and by much cultural criticism, can be read as graphically redefined through the word-image plays of Hergé's albums-and here is another pun with theoretical implications. As against the conception, ever-dominant in some "Occident" [7], of the "person" as a set of interior functions driving all externally perceptible behaviour-a conception rarely challenged in any fundamental way by even the most action-valorising films of late twentieth-century Hollywood, for example [8]-Hergé's functions of characterisation elaborate a definition of "person" that turns on what I will call "exteriority". This, then, is the second principal argument to be offered by this paper: the nature of Hergé's human figures as necessarily "graphic", in a literal sense, is cultivated, through Hergé's particular uptake of the possibilities of his drawn art, so that it generates an elaboration of the function of what I am tempted to call the "humanesque" as constituted in degrees of extremity, both figurative and logical, through the understanding of the "graphic" as the vivid and the vivid as the extreme. In the formulation just given, the "humanesque" would be a sort of shorthand for "representation of the human", and can stand where I might have said "character", to avoid confusion by indicating that it is the "complex", anthroposemic sense of character that is at issue, in this instance, not the more elemental mark. The term "humanesque" appeals, also, in that it effectively asserts that what we are dealing with here are human-like figures, semiotic construals of the human, fabricated in generically specific ways, and not some truth about personhood. Not that this should be understood as any form of epistemological escape to the province of mere matter. Like Louis Marin, we should wonder at the fact of the possibility of manipulating ink and paper to unmistakably evoke the human in the humanesque [9], viewing the fabrication of the humanesque as a basic function of humanity. And following Anne Freadman, we should see that there is no such thing as "the human", in representational terms, but rather a myriad of generic construals of what the human can be taken as. [10] Entailed in these remarks is an assertion about a general discourse on "character", a discourse that is not universally active even in my "Occident", a discourse that is to be found missing here and there where we do consider some kind of characterisation to be operative, but which nevertheless has the distinction of working itself into a sizeable range of genres reliant on characterisation. That character equates with psychology (of one sort or another), and thus with an interior dimension or "depth", is a proposition which, thanks to the discourse just evoked, is generally accepted as self-evident-whether the character in question is located in courts of law or workplace gossip or novels or theatre, or even a good number of television advertisements-hence the possibility of the unexamined charge of "superficiality" as an expression of serious dissatisfaction with some character or other (be it a co-worker or a film persona). This trans-generic remark and this assertion of discursivity made, it needs to be said that each genre will have its own, quite complex relations to the imperative of "interiority". Such generic specificity is at work, too, in any instance where the assumption of interiority is refused, and it is this which is of most interest in the present discussion. Although many BD albums engage very fully with the discourse of interiority in their execution of character-meaning that nothing in the materiality of bande dessinée precludes the signification of personal depth, and that this materiality can indeed favour such significations-Hergé's representational schema manages to effect a principle of "exteriority" in characterisation by virtue of its manipulation of BD-specific properties in a fashion that is highly assertive of the generic particularities of bande dessinée. While experimental films, novels and theatre of various sorts resist interiority and psychological drive as the necessary basis of characterisation, none of these forms has quite the combination of material conditions at its disposal that is available to the BD artist. Which is simply to say that the particular refusal of interiority constituted within Hergé's Tintin corpus is to be appreciated in its particular materiality, a materiality of iconographics and logographics. This type of concern with the materiality of the bande dessinée genre is consonant with much of the scholarly work in BD commentary to be found in the francophone literature on the subject. This critical tradition amounts to a semiotics, more or less explicitly declared as such, depending on the writer, flowing from what might broadly be described as a union of Saussure and Barthes, and inflected in individual critical cases by reference to one or more of a number of French philosophers or semioticians favoured by BD scholarship (Ricardou, Ricoeur, and Metz, for example, have a certain currency in the field [11]). To the extent that one can identify any single project carrying across the span of commentary produced in the French language with respect to bande dessinée, that is to say in a range of commentary produced since the 1960s, when the broader project of semiotics made the study of bande dessinée a worthy avenue of research, one can reasonably say that it is the description of the material properties of bande dessinée that has most often and most lengthily occupied the pages of BD commentary. Whilst on occasion these descriptions consitute pseudo-scientific taxonomies of little interpretative finesse, and whilst the taxonomic urge is rarely completely absent from BD commentary, most of this descriptive work is concerned to understand the ways in which bande dessinée materiality achieves representational complexity, how it enables semiotic systems to be manipulated. [12] The interest of the present discussion joins with and draws on some of this commentary in that it proposes to examine Hergé's work -- albeit through the example of only one album, Les Sept boules de cristal [13]- as an answer to the fundamental semiotic question of how material systems can be used (whether by readers or by makers of texts) to achieve semantic ends (the semiotic being the articulation of the material and the semantic). Numerous commentators tell us that, for Hergé, the question was contained in the term "lisibilité" ("legibility"), a term that designated his enterprise to make clear to his readers the semantic purpose of each verbal, image or more abstractly narrative element. We might have reservations about Hergé's term in view of its potential implications of authorial intention and monosemous textuality, but its acknowledgement of the challenge of coordinating mere matter to enable meaningful outcomes is important. In the case of the present examination of the issue of character, and to return to the pun set out at the beginning of this essay, it is a question of understanding how the basic iconographic and logographic characters, made available in Les Sept boules de cristal, are articulated to meet the challenge of representing the humanesque as character. In reading this modality of persona as amounting to an exploration of "exteriority", there is an investment in the notion that the graphic elements make this humanesque modality possible, but there is also a suspicion that a certain notion of the human enables a particular range of graphic plays. In any case, it will be argued that in this regime of interaction between the constitutive (the mark) and the complex (the personage), the tandem of the iconographic and the logographic works to produce a tandem of physical and narrative extremes, a tandem that is textually enabled by an articulating function of the humanesque that is conceived in terms of exteriority. Jan Baetens is one of the students of semiotics who has most usefully contributed to BD scholarship, in general, as he has analysed the workings of Hergé's Tintinian corpus, album by album. [14] Finding in the modernist impulse in much BD research an excessive valorisation of the imaged over the verbal (an overreaction, it is implied, to traditional modes of reading that favour the verbal [15]), Baetens is concerned to read the dualism of the verb-image relation, reinstating the verbal to its rightful place without effacing the image. The writing of Hergé's BD is, for Baetens, image: [16]

Baetens provides a subtle reading of the semiotics of not just the two systems, written and imaged, but of the relations between the two, and he is well aware of the shared factor of the grapheme. He finds no simple contest between the systems, but a complex of distinctions and complementarity. His minute description of the differentiated space of the speech bubble, for instance, is most instructive. To mention but one observation, Baetens takes the rampant punctuation ("la surponctuation") of Tintin as "la soumission de l'écrit à l'image". [18] This intensification of the point made in my own first argument, is the consequence of Baetens' taking seriously the manuscripted nature of the written: the refusal of typescript means that the written is composed of the same linearity as the image. What Baetens all but says is that overpunctuation forces the issue about the linearity of all writing: since punctuation is the most purely graphic element of written language, it is through punctuation that writing can be asserted as drawing. Baetens has many interesting remarks about the cross-overs between writing and image in Tintin, but special mention should be made of his efforts to understand the Hergean personages in terms of these relations between the two identified systems: his is, for instance, one of the most persuasive accounts of the characterfulness of Haddock, thanks to his detailed exploration of the particularities of the interaction of word and image in Haddock's case. Baetens does not make it his business to interrogate the very notion of character, however, and adopts a conventional language of "expression" in his description of the functioning of the word-image composite that is the Tintinian character. In a broad statement about the BD genre, for example, Baetens proposes that "l'émission verbale ne se donne à entendre que médiatisée par l'écriture. En ce sens, elle est image et muette". [19] This is as unromantic a reliance on a concept of expression as one might conceive, but it nevertheless entails a notion of interiority for the "emitting" character, the same interiority that is at the base of the notion of expression. My own notion of "exteriority" as the condition of Tintinian character can benefit from much of Baetens close analysis, but is at odds with his reading of personages as expressive. Baetens' unusually anti- materialistic reference to an audio function of BD speech is a very precise mistake as to the semiotic qualities of the bande dessinée exploited in Hergé's Tintin. It is precisely because cinema is able to produce voice emerging from mouth, and is generically compelled to do so (the films of Chris Marker show both that it is materially possible not to do so, and that it is not conventional to enact this possibility), that it is virtually impossible for film to escape the representation of character as an interior domain made manifest in speech and action. And it is precisely because bande dessinée is free from the inherent exhalation of voiced speech, from any necessary movement of speech production involving an in-to-out relation between speech and character, that Hergé's texts can enter into a representational territory where the humanesque need involve no evocation (yet another pun) of interiority.

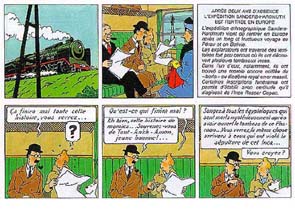

FIGURE 1: Les Sept boules de cristal, strips 1 and 2, p. 1. Click image to enlarge. One might take Hergé's minimal engagement with perspectival depth, his emphasis of the 2-dimensionality of the page and thus of superficiality, as a first step in establishing the function of exteriority as a general rule in the Aventure albums. It is also crucial to point out the role of the marked outline-the graphic foundation principle of la ligne claire and the most exterior element of the iconographic personage-as the only irreducible factor of character formation in Tintin. I will return to the matter of bodily outline, briefly, at the end of this paper. For the purposes of the present discussion, however, I will direct my remarks to the question of the dialogue bubble, with its outline and its logographic as the most compelling factors in the practice of exterioristion. This will involve a quite lengthy analysis of the opening of Les Sept boules de cristal in order to establish the workings of the dialogue bubble. This can only be done by examining the textuality of the bubble in relation to other logographic and iconographic elements. Whereas Baetens takes the speech bubble to operate as a type of "souffle" ("breath") that leaves the mouth, rising up to top of the frame [20], and in so- doing attributes an interior to the personage which is thereby producing the speech, I will argue that the graphic logic of the bubbles works as forcefully as the conditions of BD allow to deny any interiority of character, and to insist, via the character marks of speech, on the exteriority of character as personage. Much of what I have to say, below, turns on analysis of representations of movement and representations of stillness, and the differentiable logics of "source" and refusal of "source" that are in play in the logics of interiority and exteriority, respectively. The dialogue bubble, I will argue, is a supremely static function in Les Sept boules de cristal. At the opening of Les Sept boules [see figure 1], in the first frame, a train expells steam from its stack, this steam bulging across the most part of the width of the frame in curvilinear expansion: it is an image of vapour, of emission, of nebulous spread, and of a production from an inside to an outside. By contrast, the first verbal text of the the album, the first logographic text, occupies an entire frame and is given in a script to be taken as newsprint in the scriptual scheme of things (i.e. its perfectly straight strokes more clearly evoke typescript than does the slightly wavering- lined script used for dialogue): the resolutely stationary image of writing that is given here (as opposed to the very slightly tremulous effect invested in the writing of the spoken within the album), bounded by the perfectly rectilinear (though very slightly uneven) lines of the frame, admits the reading of a forceful opposition between the figure of "emission" given in the first frame, and its strip-neighbour, the third frame, in which the verbal is figured as immobile and unambiguously "present" (not departing, and quite unrelated to any point of production). Note that the intervening frame (frame 2), depicts train passengers, including Tintin, holding the newspapers that they are reading and from which frame 3's text is drawn: the verb is firmly within the grasp of the frame. The clouds of steam are drawn growing larger as they approach the border of the frame (drawn larger so that they seem to "approach" the border of the frame), creating a graphic situation where the border must "truncate" [21]the form which is posited as "stream", that is, the frame must halt the clouds' suggested movement. A similar description could be formulated for the train that produces the steam trail while travelling in the opposite direction. As distinct from this, the frame of newspaper text contains a syntactically and narratively complete chunk of news writing-there is no truncation and thus a minimisation of any sense of "run on" that might have accrued to the written word; the "chunk" is by definition a stationary figure, after all. Notwithstanding the opposition that I made, above, between the unbudging straight-stroke style of the newsprint script and the wavering-stroke style of the dialogue, I would suggest that the third frame of the first page of Les sept boules de cristal , the first occurrence of verbal text after the title, should be read as emblematic of the properties attributed to the logographic, generally, in this album: that is, that the lographic is defined in opposition to the vaporous figure of mobile emission set up at the opposite end of the strip. (Note that this is not to be taken as an opposition between word and image: the vapour trail is a particular image capable of generating particular semantic values.) That relations of similitude may be read between the typescript and the dialogue-script, is supported by the fact that the first dialogic statement of the album, produced in frame 4-the first frame of the second strip of the first page i.e. the frame following the newspaper excerpt-both designates the story told in the excerpt and projects an ending for it, linking itself to the preceding frame via a demonstrative pronoun "Ça": "Ça finira mal toute cette histoire, vous verrez...[22]". [23] This pronoun does not simply point to the preceding text, but works, within the new frame, as a shorthand that stands for the text that has just been read in frame 3 ("Ça", in frame 4, means the text from frame 3, and could be defined by rewriting the text from frame 3); it is a cross-over element between the two frames, asserting the fact that the two texts in question are made of verbal language, thus minimising the generic distinction that can be made between the typographic and the speech-graphic. Moreover, the dialogue bubble in which the "Ça" statement occurs, sits directly below the frame in which the steam trail is found, in a homologous position within its frame (close to the top of the frame, in a horizontally elongated rather than squat form), but is so different in shape from the steam emission that the comparison invited by similar positioning turns to contrast: the dialogue bubble's four boundary lines run in perfect parallel to the frame's four borders, whereas the vapour trail's border lines run in a bubble-edged, unevenly diagonal formation with respect to the frame's rectilinear structure, a formation entailing two quite different outlines for the two sides of the steam trail. The white of the dialogue bubble is so squarely bounded by the black ligne claire that it sits as a flat, contained block, whereas the white of the steam trail is shaped by the projection into it of rounded line-ends that create perspectival relations between different bulges of the trail (the decorative, "nipped" corners of the dialogue bubbles are not allowed to produce lines that might suggest volume). The latter factor, the factor of perspective, is crucial in the depiction of a moving volume of steam, which has not just right-to-left movement but a depth of field that is absent from the dialogue bubble and the newspaper text, both. Worthy of more than passing mention, this right/left movement factor raises an issue often discussed by commentators of Hergé and described by Hergé himself as of primordial importance. It concerns the stragic exploitation of the left-to-right dynamic of reading for the elaboration of forward image-movement; its manipulation is considered by virtually all commentators to be one of Hergé's greatest accomplishments. [24] Thus, while the train is depicted as moving in a line running from left to right, urging the reading effort forward as would any written line of words, the vapour trail's lines of expansion run in the opposite direction: the figure of emission is thereby defined as involving a kind of movement diametrically opposed to the kind of movement entailed within the scripted text, the latter having more in common with the figure of solidity given by the train, so far as modalities are concerned, despite the white-black graphism shared by the vapour trail and the word texts. This impression of solidity in the verbal (still another pun, here, with "impression") derives from the fact that the blockish shape of the bubbles obliges the written always to interrupt itself at the end of a short line (although very wide frames exist in Tintin, such as frame 1, p. 58, dialogue bubbles are never allowed to run wider than in "standard gauge" frames; dialogue statements can never "flow"). Trains may represent slip-stream lines of movement in other texts, but this train, like this verbal text, is a figure of no more than steady right-left movement. The suggestion of movement evoked by the stroke-style described, above, as "tremulous" and "wavering", is not, then, to be reduced to some essence of "movement" and assimilated to the movement figured by the vapour trail. Rather, the infinitessimal trace of movement in the lettering of dialogues should be viewed as an opposite type of movement, a movement going nowhere and implying no dispersal of form, an inflection of the stable solidity imaged in the typescript of frame 3 rather than a weak version of the vapour trail's mode of departure. In the light of these comments, let us look at the most distinctive feature of the dialogue bubbles: the tail. If the nipped edges that suggest the static positionality of framed portraiture are not a sufficiently compelling reason to abandon any thought of comparison with "breath", the quality of the tail should be. It is important to note, as numerous commentators remind the Tintinologue, that European comics had not discovered the speech bubble and its indexical graphic when Hergé set about making Tintin. Hergé is, then, the pioneer of this function in European comic history, and does not simply follow U.S. conventions. Most crucially, for my point, Hergé's convention in the drawing of the tail is quite different from some of the most famous U.S. instances. I am thinking of instances where the tail has a smoothly curved form that grows markedly wider, the closer the tail gets to the point where it will seem to attach to the bubble of which it is, in fact, an integral part. This tail is a figure of expansion and creates the effect of an emission from the character indicated by it. Quite distinct from this is the zigzag form of the Hergean tail, which follows no direct line like that of an expelled puff of breath, but rather seems to reach down from the top of the frame to the personage to which it is connected, just as the lightening bolt comes down from the heavens [see figure 1, frame 4]. Notice that the zigzag has a somewhat flabby bend to it, rather than a lightening-bolt angularity, and this counteracts any strenuous dynamic that might have resulted from the zigzag form. The tail always stops short enough of the head to which it points to further reduce dynamism. Any suggestion of movement is, then, minimised. Far from the bubbles appearing to have risen up from the characters, they sit squarely above them. The very fact of the rectilinear form of the "bubble"-as opposed to the rounded form, favoured by U.S. artists, that made the term "bubble" make sense-militates against an effect of movement, particularly upward movement: although the term "bulle" ("bubble"), which seems to have come into French usage around 1960, doubtless under U.S. influence, is now very common in BD culture, the more original French term "phylactère", with its formal antecedents in first religious amulets then medieval painting, makes no such claim to expansive roundness in the manner of the gas bubble, but rather evokes the fixed-form of a box or a rectilinear banner.

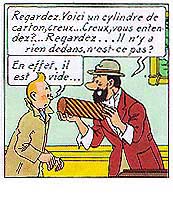

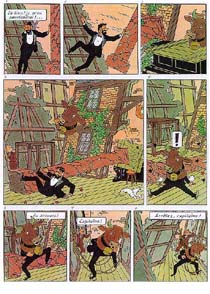

FIGURE 2: Les Sept boules de cristal, p. 5, frame 14. This examination of what we must now call the "dialogue box", that is to say, this examination of the disposition of the trait that surrounds the logographic text, demonstrates that the graphic logic of this logos-shaping outline amounts to so many refusals of continuity effects with the icon-shaping outline. In other words, there is here a graphic logic of correspondence between iconologic characters and iconographic characters, rather than a relation of production, with speech issuing from some basically constituted personage residing in the image. The Hergean logic of personage, readable from the qualities of the dialogue box in its relation to the humanesque image, posits a notion of "character" (in the composite sense), as essentially "without"-and this term should suggest both non-unity and exteriority-as follows logically from its foundation in "characters" (marks). Those comic works figuring speech as emerging from within personages offer a notion of "character" as essentially "in possession", founded in continuity. Hergé's clear separtion of the iconologic and the iconographic (another construal of la ligne claire), including the refusal of any fiction of speech emission, makes characterfulness reside equally in image and word, in the two types of elemental character (even though basic character formation is performed by the iconographic). The bodily form is not the seat of the verb-and as any Tintin reader knows, the word, and particularly the dialogic word, is much more creatively exercised in Les Aventures de Tintin than in The Adventures of Superman. This conclusion need not so much run against Baetens' reading of the written as "submitted" to the imaged (though we now see that his metaphor does not take account of writing's literally superior position in the frame), as suggest that there is another relation to consider than the centuries-old binary tussle between writing and image, and it is a tripartite relation among the iconologic character, the iconographic character, and the characterful character that results from the co-ordination of the first two functions. Baetens' work is effected by (although, given his attention to textuality, by no means completely reducible to) a common error in BD commentary written under the authority of a certain "semiotics", and that is the error of finding in particular and local textual features only the cipher for monoliths of semiotic history or for genera in a taxonomy of semiotic entities. Although the present discussion is clearly engaging with semiotic classes (but "species" rather than "genera", I think)- "iconographics", "iconologics", "character"-I would argue not only that textual specifics are shaping the classifications but that the particular class which is "character" is especially useful for pushing analysis towards the examination of the textual "ecosystem" (to sustain the biological metaphor), and away from the stereotypes of generalisation. Baetens looks at those cases of image-word relation where the head of a personage enters the space of the dialogue box and forces the writing to split apart in mid-word or mid-sentence in order to accommodate the image [see figure 2]. Baetens reads this as proof of image's superiority over writing. [25] It is true that the head never gives way to the word in the same manner, but given that the word is not obliterated by the head, its "submission" is slight and might be more properly described as a partial "accommodation". When this sort of example is read with not just the image-word binary in mind but also the problem of character, the unharmful penetration of the iconologic space and splitting of the iconologic lines by the iconographic space of the head can be taken as a strong assertion of the graphic nature of the verb, certainly (one thinks of Godard and his principled use of disruption to emphasise the materiality of film), but also of the existence of a relation between iconographics and iconologics that is governed by both elemental and composite functions of "character". The outlines of the iconographic and iconologic spaces meet-one cannot strictly say whether the box's line has been broken or whether it has merged with that of the head, the elemental traits of word and image being identical in nature. But this conjoining of the two domains of the composite that is character-as-personage does not simply dissolve all difference between word and image, nor establish some hierarchy of importance: it can be read as a limit case that asserts the relation of co-ordination between iconographics and iconologics for the purposes of a specific working notion of personage, a co-ordination dependent on an ultimately strict separation of the two character functions. If the bodily character can be seen to intrude upon the space of the word characters, it is obvious that the latter do not belong to the former, and it follows that they have not emerged from the former. Figure 2 gives an instance, then, of the resolutely non-unified nature of Hergean character. The dialogue in this frame is as follows: Haddock: "Look. Here is a hollow, carton cylinder ... Hollow, you understand? ... Look ... There is nothing inside, right?"; Tintin: "Yes, indeed, it is empty...". The personnages of Tintin and Haddock are no more full of words waiting to emerge than the cylinder contains magic properties. The interiority of the cylinder will fail to produce anything in the magic trick of transformation that Haddock attempts, and no personnage is ever attributed with even this much productive interiority. [26] The pedantic care that I have taken to establish the dialogue box as a figure and a mechanism of unsourced remove, with respect to the imagery of bodies, is proportionate to the importance of disturbing the presumption of interiority that governs the general understanding of character, which speech is taken to confirm, speech being said to "come from the heart" or the from the interior of the head when one "speaks one's mind". Hergé's dialogue boxes sit at the very top of the frame, a bare millimetre from the frame border in almost every case, and only come close to a personage's head when pressed down towards it by the sheer volume of verbality [see figure 1, frames 5 and 6; figure 2], or when some movement of a body in the frame pushes that body into the space of speech. Within the confines of the usually tight space of the Hergean frame, speech, through the positioning of the dialogue box, occupies an extreme position in the BD microcosm, at maximal remove from the body to which it points. The iconologic characters and iconographic characters are in a relationship of graphic extremity: any greater remove would undo the graphic relation enabling the composite of characters that is character or characterfulness in bande dessinée; the degree of remove actually negotiated by all Tintin frames containing dialogue permits its thematisation as both exteriority and extremity. My title indeed promises a thematisation of this extremity, and this thematisation involves reading character, in the composite sense of "personage", as existing in extremis. We know that the title of the series is Les Aventures de Tintin, and adventure is a genre that places its hero in extremis on a regular basis (attack by gunfire, threat of avalanche, condemnation to ritual sacrifice by burning). Readers of Tintin also know that most of the stories take Tintin and his companions away from their homes and indeed their homeland, to the extremities of the world known to them (to some totalitarian Eastern Europe, to China, to Peru ... though they do not make it to Sydney, doubtless far too uneventful a city to satisfy the criteria of extremity). But there is something else at work in the Tintin stories, be they set at home or away, that is a more fundamental exercising of extremity. The Petit Robert dictionary offers the following example for the expression "in extremis": "Rattraper in extremis un objet qui va tomber". Catch an object that is going to fall. It is the last instance of usage in the entry, at some remove from the death throes that open the dictionary's account of the Latin expression. It is a banal usage for a striking locution. As it happens, the depiction of the humanesque offered by Les Sept boules de cristal, in particular, and by the series in general is far more consistently about the problem of catching things before they fall-or perhaps oneself-than it is about the penultimate moment before death. The problem with being a composite entity known as a "character" is precisely not one of struggling with some burden of interiority, but of struggling with the essential exteriority of personage that is made out of graphic characters: the problem is that there is little to distinguish the humanesque figure, separated from the power of speech, from the objects which surround the figure, objects made of the same trait. Indeed, the subject/object distinction becomes a precarious one, since there is no material difference between humanesque figures and others (and this precariousness is acted out in the drawing of object-subject relations). The graphicness of this generic fact is maximally exploited by Hergé, since he refuses to allow the humanesque sole access to the fiction of movement: objects move and most particularly fall, with disturbing regularity, and humanesque figures get caught up in the trajectories of those objects almost as much as they determine or get caught up in their own trajectories. These personages, whose speech is not a descendant of the ancient trope which makes verbality the expired conversion of inspiration, have had no spiritual property breathed into them, and, not being inspired, cannot be saved from their material predicament by any spiritual transcendance over the world of objects. Solutions will always be based in the organisation of (provisional) material equilibrium. Figure 3: Les Sept boules de cristal, p.15. Click image to enlarge. There is a great deal to be said about the play of order and disorder in the tales of Tintin, and Michel Serres has demonstrated this. But lacking a semiotician's concern with textual materiality, Serres has not explored the drama of character that is played out in the detail of generic specificity. Baetens has gone much further in this, and the present discussion is something of a complement to Baetens' detailed study of numerous textual mechanisms governing the relation of words to image and to various personages. Serres is, however, the model for taking Hergé seriously, and taking Hergé seriously permits one to find not just textual mechanics at work in Les Sept boules de cristal, but a graphic thesis on the humanesque. The slapstick imagery of the accident-prone Haddock, launched into a series of mishaps involving a domino-effect of falling objects, enacts the problem of character as a problem of maintaining one's character traits in the face of the encroaching traits of the object realm [see figure 3]. Haddock is only Haddock when in catastrophe, but cannot be Haddock if he loses his head completely to the imposing force of objects: by the rule of co-ordination and correspondence between logographics and iconographics, discussed above, the characteristic oaths and insults that have made Haddock the personage par excellence in the Tintin series cannot attach to some other figure, and Haddock cannot be Haddock without them. This is where the banal and the grave senses of "in extremis" are brought into relation, and it is the basic difficulty of maintaining the object/subject divide in the material world that produces this relation. The corporal outline that is occasionally allowed to come as close as merging with the iconologic outline, in the cooperative graphic relation that enables the subjecthood of character to be defined, is susceptible to being drawn into obliterating relations with object outlines-Haddock's trait of character that sets him to having to catch himself from falling, places him not just among objects falling but makes of him an object, because he has a capacity only for falling, not for stopping the fall: his trait, then, makes his trait vulnerable to realignment in the shape of a mere object. A cow of a situation to be in. Or a monstrous one, where the monstrous is the disturbingly multigeneric. The figure of the bovine-headed human torso presents most concisely the problem of maintaining the subject- object divide. This, then, is a treatise on the humanesque to be generated out of the complexities of "character" that are exercised in Les Sept boules de cristal: character formation is dependent on the most elemental material arrangements, but challenged by more composed forms of disruptive matter. This challenge is the stuff of which Tintin stories are made. The tension of philosophical proportions in this album, and arguably in all Tintin stories, is not between word and image, which operate in a relation of distinctness but not of conflict-it seems that we can equally well say that images, being made of the same line as writing, are statements, or that writing is drawing. The tension of philosophical proportions in this album is between subject functions and object functions, and it is the same ambiguity in the term "character"-the one that allows for cooperation between the iconologic and the iconographic-that provides the relational mechanism for exploring this tension: the abstracted, complex, semanticised sense of "character", in Hergé's bande dessinée, derives from the basically material one and can revert to that material, subject-less state. Of course, it must be a premise of a semiotic understanding of character in any genre that it has a material constitution, but Hergé's art of character pursues the implications of that fact in an unrelenting fashion. As to whether the treatise on the humanesque deducible from this art has anything to say about the human, in the way that Serres seems so passionately to want Hergé's corpus to do, well that is quite another ... matter. Notes:

1 I will use the French term for the

genre-literally translatable as "drawn strip"-rather than

"graphic novel", since the latter term suggests a rather more sobre

and literary affair than is presented in many of the works within the bounds of

bande dessinée. Although the term "comic albums" comes

closer to the unpretentious, catch-all semantic of the French term, it is

problematic for the opposite reason, in that it does tend to evoke, for the

Anglophone reader, a set of things excluding the variety of serious narrative

enterprise and aestheticised graphic styles readily found in Francophone but not

in English-language "comics".

2 Hergé, himself, had some

reservations about the way in which the term was applied to other BD artists. In

his final interview, conducted by Benoît Peeters on 15 December 1982, a

few months before his death, Hergé insists that the "ligne

claire" entails a narrative quality as much as a graphic one, and bemoans

the fact that numerous artists upon whom the title is conferred, although

working with an appropriately minimalist graphic style, fail to make their

stories "clear". One might conjucture that Ted Benoît's

remarkable 1982 album, Berceuse électrique, with its puzzling

multi-generic pastiche of what might best be called narrative componentary,

might well have earned Hergé's disapproval, despite Benoît's

status, in many commentators' eyes, as the principal inheritor of the

"ligne claire" mantle. See "Conversation avec Hergé"

in Benoît Peeters, Le Monde d'Hergé (Tournai:

Casterman/Carlsen, 1990) 204.

3 The commonly-used abbreviation for

bande dessinée, "BD", is quite acceptable in scholarly

works on bande dessinée written in French, and will be used in

adjectival positions in this paper, for reasons of lexical convenience.

4 Hergé, "Comment naît

une aventure de Tintin", in Le Musée imaginaire de Tintin

(Tournai: Casterman, 1980) 10-16: "text and drawing are born

simultaneously, each supplementing and explaining the other" (10). The

translation is mine, as are all other translations in this article. I will err

on the side of literalness to allow certain metaphorics to remain clear.

5 This entire discussion runs the risk of

forgetting that the "graph" is not the sole province of the iconic,

thanks to everyday usage of "graphic" in a way synonymous with

"imagistic". Etymologically, "graph" is perhaps more

strictly the mark of writing. In any case, in Hergé's system, since both

writing and image are "drawn", no real conflict between ancient and

modern senses need arise.

6 Jan Baetens does not make a

terminological shift of this sort, but does offer a very nicely turned

discussion of the way in which the choice of lettering in Hergé's

Tintin works: Jan Baetens, Hergé écrivain (Brussels:

Editions Labor, 1989). For Baetens, the writing's form "attenuates the

possible opposition between word and image" (72). See, in particular

the chapter "Les Dupondt, des lettres dessinées" (65-80), where

the title, "The Dupondt (The Thom(p)sons), drawn letters" makes

Baetens' point very succinctly.

7 I hesitate to use the term

"West", since it is the term uttered enigmatically by Tournesol

(Calculus) in a number of albums, and indicates, most clearly in Les Sept

boules de cristal, Europe's sublime geographical "west", the

Americas. This article, being written from Australia, cannot entertain any

simplified geographical notions of what the "West" means in the

shorthand used to designate "Western-European-derived cultures". The

geographics of the cultural entities deriving from Western-European cultures,

yet located in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia,

Singapore and South Africa, are such that it becomes clear that the problem with

using the term "the West" is not only one of Eurocentrism, but of

East-Westism: even retaining Europe as the point of reference, "the

world"-when viewed from one of these countries-clearly fragments and

probably decentres, since "the West" is also at least one

"East", and a number of "Souths".

8 The reputedly "superficial" characters played by the Stallones, Schwarzeneggers and Van Dammes of Hollywood action drama, antithetical types of character to those of, say, French psycholo

gical drama, are nevertheless established in terms of some driving psychological core. Or consider, for example, the telos of character formation that is made evident across the "Terminator" series, despite the lack of any such emotional core to th

e Terminator in its first incarnation: the indestructible, emotion-free cyborg of the first film comes, in the last, to strive not only to understand the human "interiority" of emotion, but to acquire the movements of that interiority. The shedding

of a tear before his suicidal parting from his human friends is the external guarantee of the cyborg's interior development. In this filmic treatise on the nature of humanity, it becomes clear that, while any cyborg may reproduce and surpass the human fa

culty of bodily movement, the true preserve of humanity-which only a trans-species miracle can reproduce in the fundamentally non-human entity of the cyborg-is that of interior movement, of emotion. Thus, for his definitive, self-inflicted ontological exi

t, the good-guy cyborg renounces the extremes of physical movement that have characterised him, moderating them in a process of diminishment that first divests him of auto-motion, as he abdicates his own power of movement to that of an industrial hoist, t

hen eliminates even this prosthetic movement by taking it to the point of disappearance through a slow, rope-borne descent into the molten brew. If the initial figure of the Terminator consituted a radically anti-Romantic definition of character, the seri

es as a whole ultimately capitulates to the force of the Romantic notions refused in the first place-as if longevity of character (a span of seven years separates the 1984 original and its 1991 sequel) must ultimately resolve into emotional depth of chara

cter, a depth so deep it sinks.

9 I am liberally glossing Marin to suggest that one of his fundamental gestures in respect of the image does indeed involve paying respect to the capacity of the merely material image to ev

oke the affect-laden or power-rich human. Of course, Marin deals with instances of the "humanesque" of a far more serious type than Tintin and Haddock-the picture of the deceased beloved on the mantlepiece, the portrait of the king, the word-image of the

risen Christ. See, for example, Louis Marin, "L'étre de l'image et son efficace", in Des pouvoirs de l'image (Paris: Seuil, 1993) 9-22.

10 Within the substantial body of work by Freadman treating the question of generic representational specificity, I am most mindful, for this point, of her recent study of La Princesse

de Clèves which includes an injunction to read for representations of women in a generically precise way, and an exemplary demonstration of the fruitfulness of such an approach through the study of the Princesse. See Anne Freadman, "Ref

lexions on Genre and Gender: The Case of La Princesse de Clèves", Australian Feminist Studies, 12.26 (1997): 305-320.

11 It is interesting to note that Michel Serres' virtuosic readings of Tintin albums are referred to relatively little in the commentary corpus to which I refer, despite the recurrent ref

erence to Hergé in this corpus. This may be a function of the fact that generic description is the prime concern of BD commentary, whereas Serres offers readings that elaborate philosophical problematics evoked by the B.D. texts in question, with l

ittle clear reference to structural features. See Michel Serres, "Rires: les bijoux distraits ou la cantatrice sauve" in Hermes II. L'Interférence (Paris: Minuit, 1972) 223-236; and Michel Serres, "Tintin ou le picaresque aujourd'hui", in Critiq

ue, 358 (1977): 197-207.

12 For a most sophisticated and lucid study of bande dessinée's semiotic possibilities, see Benoît Peeters, Case, plance, récit (Tournai: Casterman, 1991

).

13 Hergé, Les Sept boules de cristal (Tournai: Casterman, 1948, 1975), (The Seven Cristal Balls). I claim for the present argument that it pertains to a good many of

the Tintin albums, but perhaps not to all. The description and analysis that I am offering of Les Sept boules de cristal seeks to establish the operation of a certain semiotic order of character, not the universality of such an operation wit

hin the Tintin corpus.

14 Jan Baetens, op. Cit.

15 A substantial list of writings demonstrating the validity of Baetens generalisation could be given here, since BD scholarship has indeed been heavily committed to redressing an oft-ass

erted historical imbalance in the privileging of the verbal over the imaged. Suffice it to mention, here, just two critics who act as champions of the image, and who risk the charge of neglecting the verbal in their BD studies: Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle,

"La BD ou le tableau déconstruit" in Fresnault-Deruelle, L'Eloquence des images (Paris: PUF, 1993) 195-206; Marc Avelot, "L'encre blanche" in Thierry Groensteen, Bande dessinée: récit et modernité (Futuropolis, 1988) 157

-173.

16 Baetens, op. Cit., 28.

17 Baetens, op. Cit., 65: "To reduce, in a bande dessinée, words and letters to their linguistic dimension, without recognising the force of their visual aspects, wou

ld clearly be the worst kind of misinterpretation. As soon as we see their covers, the albums of The Adventures of Tintin remind us of this, in fact, since they sometimes modify the shapes of letters to the specific contents of a volume".

18 Baetens, op. Cit., 72: "the submission of the written to the image".

19 Baetens, op. Cit., 28: "the verbal emission does not offer itself to be heard except mediated by the written. In this sense, it is an image and mute."

20 Baetens, op. Cit., 70.

21 Benoît Peeters has a vivid metaphor of truncation at work in his theory of segmentation as it is presented in his Case, planche, récit: depicted objects are

said to be "tranchés vifs par les limites de la case" ("severed alive by the boundaries of the frame"), Benoît Peeters, Case, planche, récit, op. cit., 20.

22 It is important to distinguish between editorial ellipses and the "three dots" that appear regularly in Hergé's script. These should be understood more often as "suspension poin

ts" ("points de suspension") than as indications of ellipsis. Hergé's dots will appear in my text, as in the album, without brackets, and without spaces either between them or between them and the immediately preceeding word.

23 Les sept boules, op. Cit., 1, frame 4, "It will all finish badly, this story, you'll see...". Literally: "That will finish badly, this whole story, you'll see...", where

the "That", ungainly in English, stands for the conventional usage of "Ça" in French.

24 On this point, as on so many others involving Hergé, Benoît Peeters is once again an extremely helpful reference: see his discussion in Case, planche, récit,

op. Cit., 58-61.

25 This type of splitting is, incidentally, proof that the notion of the bubble as "breath" is unsustainable: the phylactère's contents split apart, like something so

lid; they do not envelope the head or waft away like so much gas escaping from a bubble.

26 Haddock is, of course, a drinker, and this makes of him a recepticle; he has an unproductive interior: things always go awry when Haddock asserts an interiority by drinking; Tintin nev

er attempts to establish such an interiority and does not encounter the sort of trouble met by Haddock.

Works Cited:

Jan Baetens, Hergé écrivain

(Brussels: Editions Labor, 1989).

Benoît Peeters, Case, planche,

récit (Tournai: Casterman, 1991).

Benoît Peeters, Le Monde d'Hergé

(Tournai: Caterman/Carlsen, 1990).

Anne Freadman, "Reflexions on Genre and Gender: the

case of La Princesse de Clèves", Australian Feminist

Studies, 12.26 (1997): 305-320.

Hergé, "Comment naît une bande

dessinée", in Le Musée imaginaire de Tintin (Tournai:

Casterman, 1980).

Hergé, Les Sept boules de cristal

(Tournai: Casterman, 1948, 1975).

Louis Marin, Des pouvoirs de l'image (Paris:

Seuil, 1993).

Michel Serres, "Rires: les bijoux distraits ou la

cantatrice sauve" in Hermes II. L'Interférence (Paris:

Minuit, 1972): 223-236.

Michel Serres, "Tintin ou le picaresque aujourd'hui",

in Critique, 358 (1977): 197-207.

|